Great gigs are the ones that get “picked at.”

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

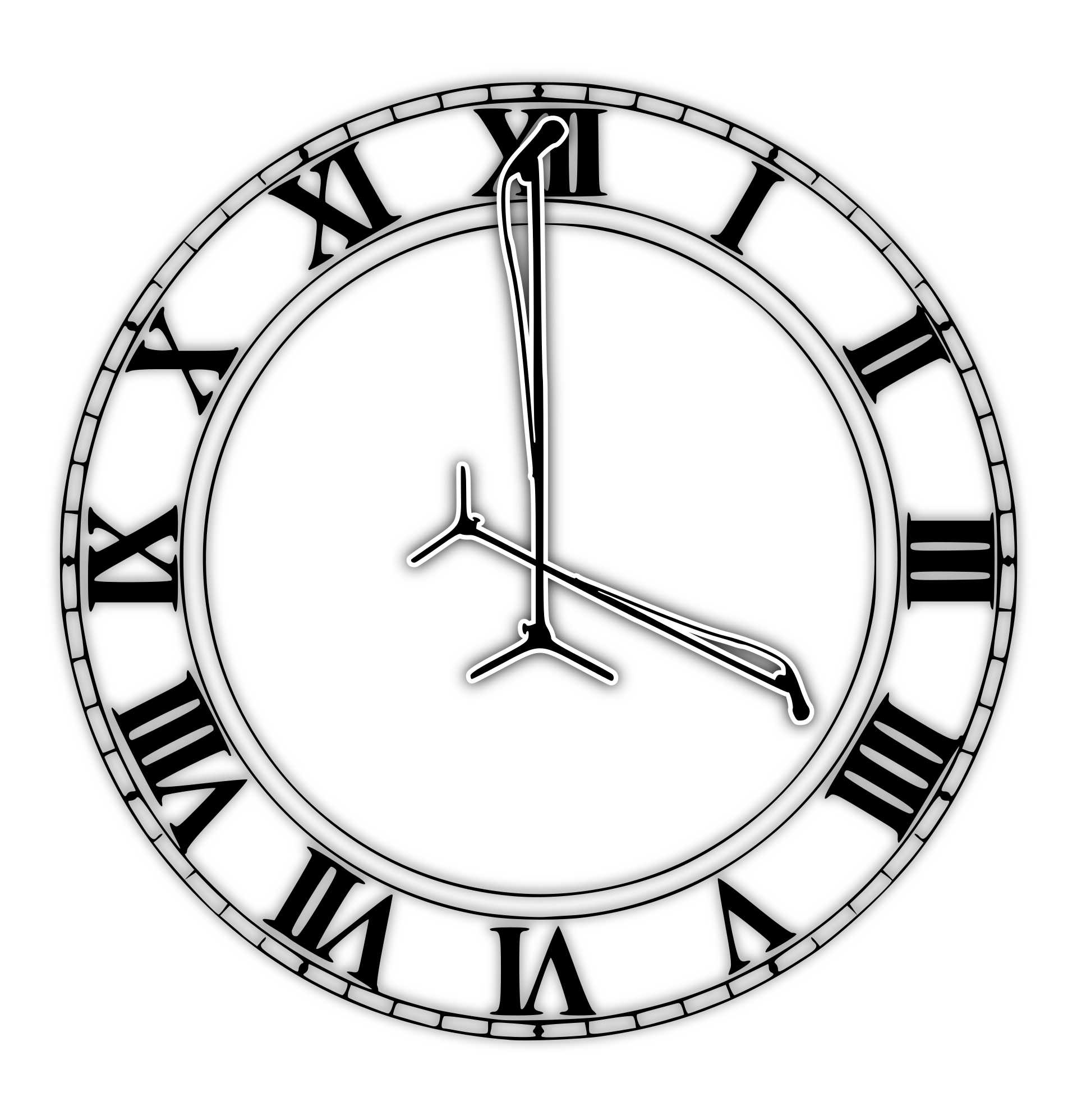

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.There’s a point where a guys starts repeating himself; I have certainly reached that point here. Nevertheless, repetition of theme without rote regurgitation of content can be useful. So, I’m going to talk some more about time, and gigs, and showing up, and how it impacts success.

And I’m going to do it by borrowing the words of Jason Giron from Floyd Show and Loss of Existence. There was an occasion where a fellow band member asked, “When should we come to soundcheck?”

Jason replied, “When do you want to sound good?”

I tell you, every so often you get to stand next to someone who can perfectly encapsulate a tome of wisdom into a single sentence. This was one of those times for me.

There are plenty of bands, individual musicians, and production humans out there who want to minimize their exposure time when it comes to a gig. This is understandable, because in Western society, time and money sit on either end of an equality symbol. The problem, though, is that minimizing your on-gig time has an alarming tendency to minimize your on-gig success. When it comes to show production, getting the really amazing things to happen requires “picking at it.” Picking at it isn’t time and money efficient, but it’s necessary to create magic.

If you want to really get comfortable with how everybody sounds on a stage with no reinforcement, and truly dial that in so that the future reinforcement will be maximally effective, you have to take the time to pick at it. It doesn’t happen in the space of a minute. You actually have to get up there, play some songs, and figure out how everybody fits around everybody else.

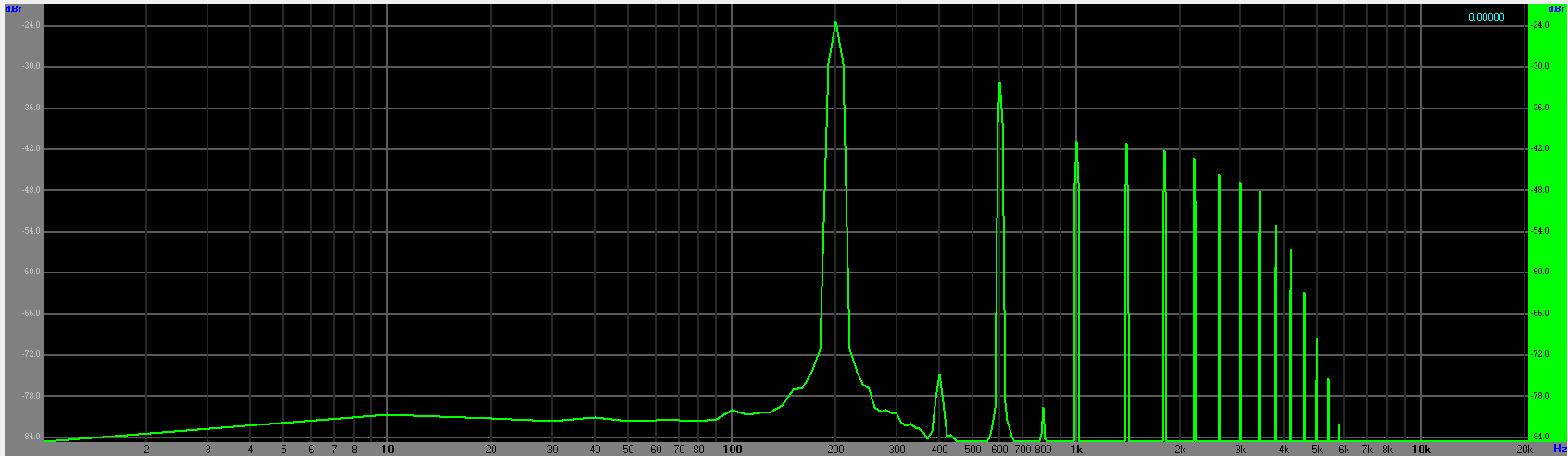

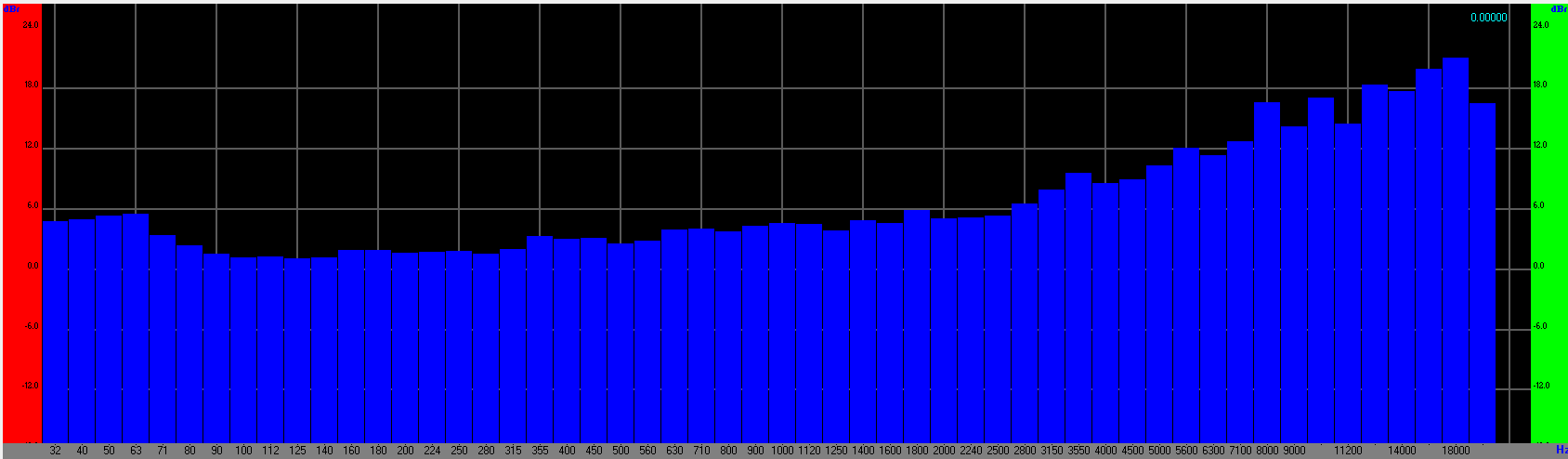

If you want to dial up a truly killer starting point for monitor world and FOH, you have to pick at it. You can’t just throw it all up there, run a few test signals through, and walk off for a bite. You have to actually go up on deck and listen to a real mic through a real wedge. And then listen to a real mic through multiple wedges. At high gain! You also have to listen to real music through the FOH rig. If you want an objective measurement of the system, you have to get out your reference mic and attendant software, and then take a few minutes getting a good trace.

If you want me to create the best monitor mix possible for you in that room, you have to pick at it. We have to go through several iterations of tweak/ listen/ tweak/ listen/ tweak – and we have to be able to do it all with calmness and rationality. Thirty seconds of panicked gesturing from a cold start ain’t gonna get you there, pilgrim.

If you want to build the FOH mix that effectively translates what the band is doing into the house, leveraging and flowing along with the natural sound of the group in the room…You. Have. To. Pick. At. It. Before doors. Or do you want to be futzing around, “finding yourself” for the entirety of the first set? People, please. Bands and audiences deserve better.

As an experienced “Selective Louderization Specialist,” I can tell you that sounding good (and getting everybody truly comfortable) takes at least an hour of work. Bare minimum. (There are plenty of bands that require much more time than that.)

And that hour does NOT start until everybody is in the same room, with all the gear working, and with the entire audio system pre-tuned for the appropriate performance. (A hint for sound people: You have to be really early if you want a fighting chance at this.) It’s not to say that it’s impossible to sound decent in a smaller span of time. It can be done, and sometimes it must be done – but why choose that outcome if it’s optional?

“I’m not required to smack myself in the face with a sharp object, but I’m going to do it! Eugene, hand me that axe!”

Really?

Assuming that it’s going to take no less than 60 minutes of effort to make your show spectacular, I encourage you to ask yourself the “Giron Question.” When do you want to sound good? Figure out when that time is, and then show up a lot earlier than that.