Production success has just as much to do with logistics as with any other factor.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.Last week, I worked on a special birthday show for Amanda Grapes. Amanda handles various fiddle and vocal duties for The Nathan Spenser Revue, The Puddle Mountain Ramblers, and The Green Grapes Band. All three groups played that evening. It was excellent. I also enjoyed the cupcakes.

My opening sentence makes it sound like the day of the gig was the day that effort was put in. Actually, Amanda, the other band members, and I worked on putting the evening together for over two weeks – and that, right there, is a stumbling block that has tripped up a good number of bands. There are plenty of folks who think that the most important work on a show happens just before downbeat. That’s incorrect. Loading in, setting up, getting checked, and all that great stuff is the most ACUTE work of the show, but that activity is preceded by the logistics that make it all meaningful.

The more work I do in this business, the more I see “production execution” as entailing almost trivial concern, and logistics as a major factor that has to be worried over.

Why? Well…

Just Getting The Date Settled Is Hard

Think about the challenges involved in wrangling a band of 3-5 people. Imagine the schedules that have to be coordinated to both practice for, and arrive at some sort of show. Now imagine doing that across three separate bands (11 regular players), a couple of guests who’ll be sitting in, and an audio human. Now visualize doing that while trying to nail down a “moving target” date with the venue booker.

Sound “fun?”

In this environment, the organized have a much better shot at survival than the disorganized. Yes – there are artists who do well in spite of not really being “with it,” but I’ll bet a good percentage of that cohort is being helped along by people who are REALLY good at managing the details.

Being proficient at managing these kinds of logistics is a big part of what separates the “varsity level” bands, venues, and production personnel from the JV crowd. Shepherding such details is the very root of getting shows done, because if the scheduling doesn’t happen, then…what?

No show. At all. Discussing the production doesn’t even matter, because there’s no production to do.

Further, handling the details just well enough to land the night, but not well enough to really know what’s going on – well, that ends up putting a lot of stress on the production side of things. If you don’t know who’s going to show up, and with what, then how do you prepare production for the gig? Your effectiveness drops like a rock. You either have to over-prepare (which isn’t necessarily bad, but can be annoying in larger doses), or just throw things together at the last minute (which can be a recipe for awful production, riddled with technical difficulties and evil surprises).

On the other hand, it’s a joy to work with the folks who are effective at getting the whole herd pointed in the same direction and moving at the same speed. Things just become easier.

It Ain’t A Good Plan If It Won’t Fit The Van

Another make-or-break factor that rests on logistical prowess is making sure the production fits the boundaries it’s going into. One such boundary is the transport of all the gear and people involved, which I won’t detail here.

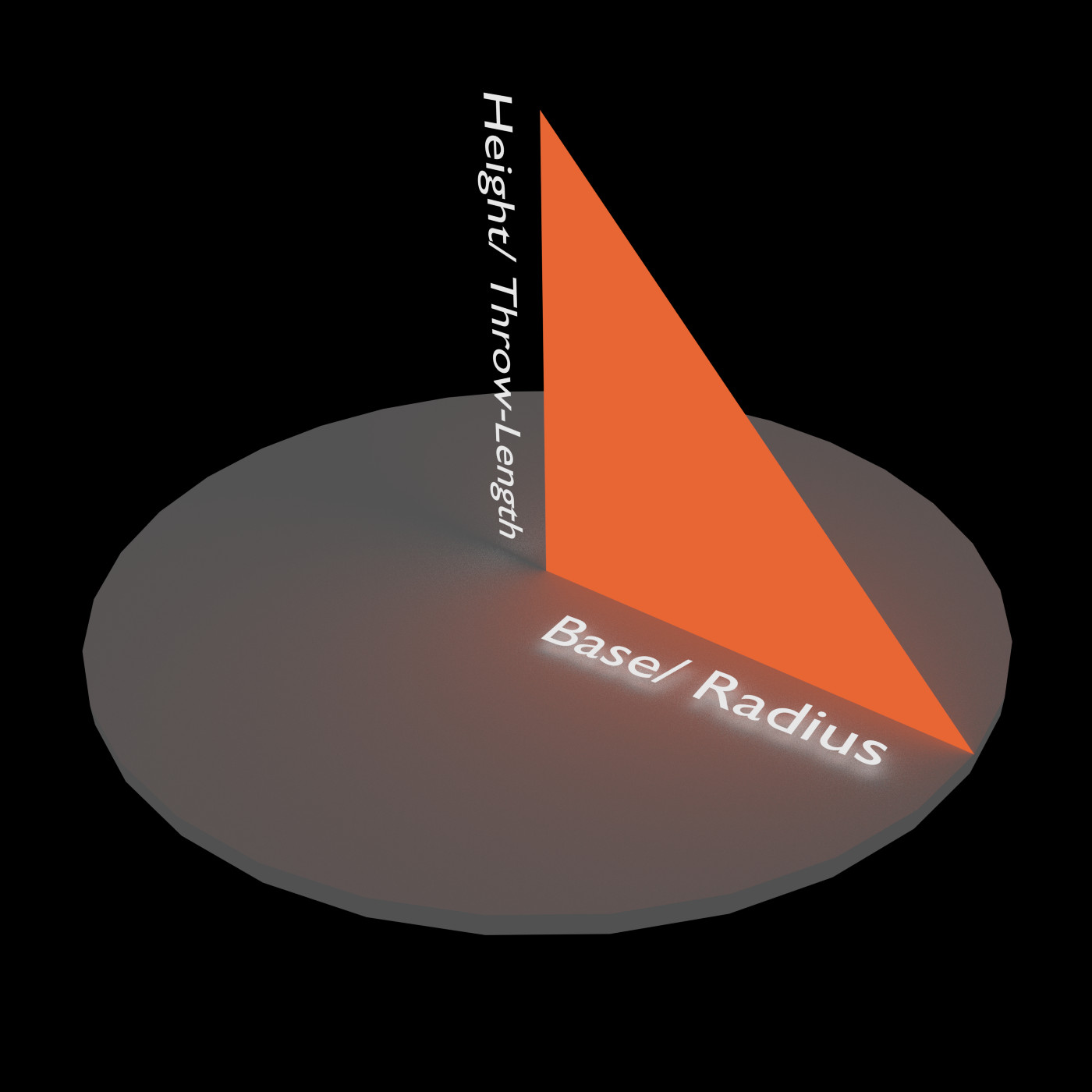

A boundary which I will get into a bit is that of venue production – and this lies near the core of my feeling that “production is easy, and logistics are tough.” At some point, production techs begin to realize that the biggest shows, with the most complex execution, are just lots of simple bits that are plugged into each other. A 10,000 scene light show is built a step at a time. You need to do some weird thing with lots of mics and lots of monitor wedges going every which way? It’s not really a big deal if you arrive on time, and the routing and hookup is handled methodically. The problem really isn’t the number of “moving parts,” just by itself. The problem is the number of moving parts can be practically stuffed in the box that is the venue.

Figuring that out is logistics, and thinking is DEFINITELY required.

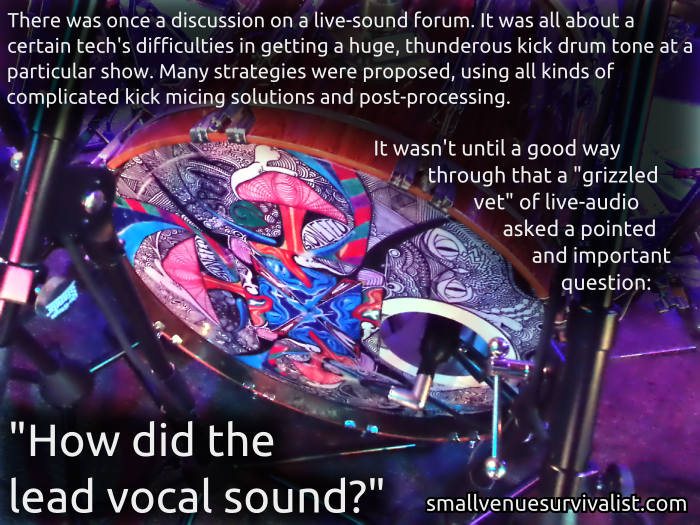

This is why audio humans love to get accurate input lists. It’s also why we like getting an accurate picture of how bands want the night to develop. We like to get both because the intersection of the input list with the show-flow is “A Very Big Deal Indeed.”™ It’s “A Very Big Deal Indeed”™ because a show that isn’t repatched midstream can easily overrun the capacity of the stage or mixing console.

And many small-venue gigs are not repatched in the middle, because reworking what’s going into the snake can be pretty challenging when you only have one production person on hand.

In fact, I very nearly got “bit” by a channel overrun problem on Amanda’s show. It was because I temporarily became lazy about working out that intersection between the input lists and the show’s progression. I read the input requests that I’d been given, but only considered them individually from band to band. Turning them over in my head, everything seemed dandy. The day before the show, though, my cautionary inner voice started to nag me:

“You really should write this all out.”

I listened to that internal warning and wrote up an input list that considered how the night would actually happen: We were not going to repatch anything. Every channel had to be ready to go from downbeat to the last note, because there wouldn’t be time to futz with what was going on at the snake head.

It was lucky that I wrote out the no-repatch input list, because it exposed a problem that I hadn’t considered. Without a repatch, we would not have enough channels to do the show “exactly as written.” If I had just gone, “Yeah, yeah, we’ll be fine,” the show would still have happened – but we would have had to cut down the drum mics at the last moment. That would have been unpleasant and unprofessional.

…but armed with my discovery, I could now use another bit of good logistics to manage the problem. I could call the drummer’s number (which I had been thoughtfully provided with in advance) and discuss the options ahead of time. We decided that he would submix the drums to two channels, which neatly fixed our “not enough inputs” problems, and there were no surprises on the actual day of show. Much better.

**********

The point of all this is that, again, the assembly and operation of a show’s production is basically academic. You place and plug in what you need, check that it’s working, suss out the connection problems and the feedback issues, and off you go. What makes it possible to be effective and focused in that process is the organizational work that “sets up the setting up.”

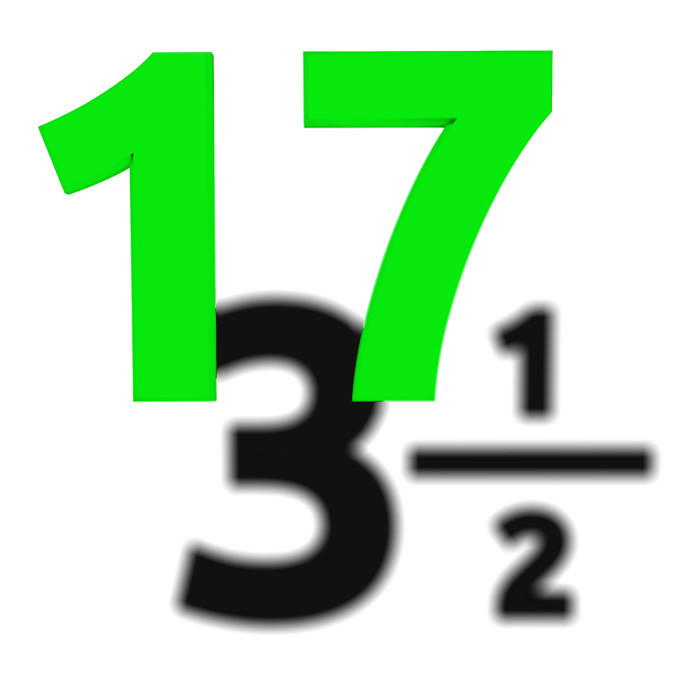

That’s why it can take 17 days to do a three-hour and thirty-minute show.