Nozzles increase fun for everyone.

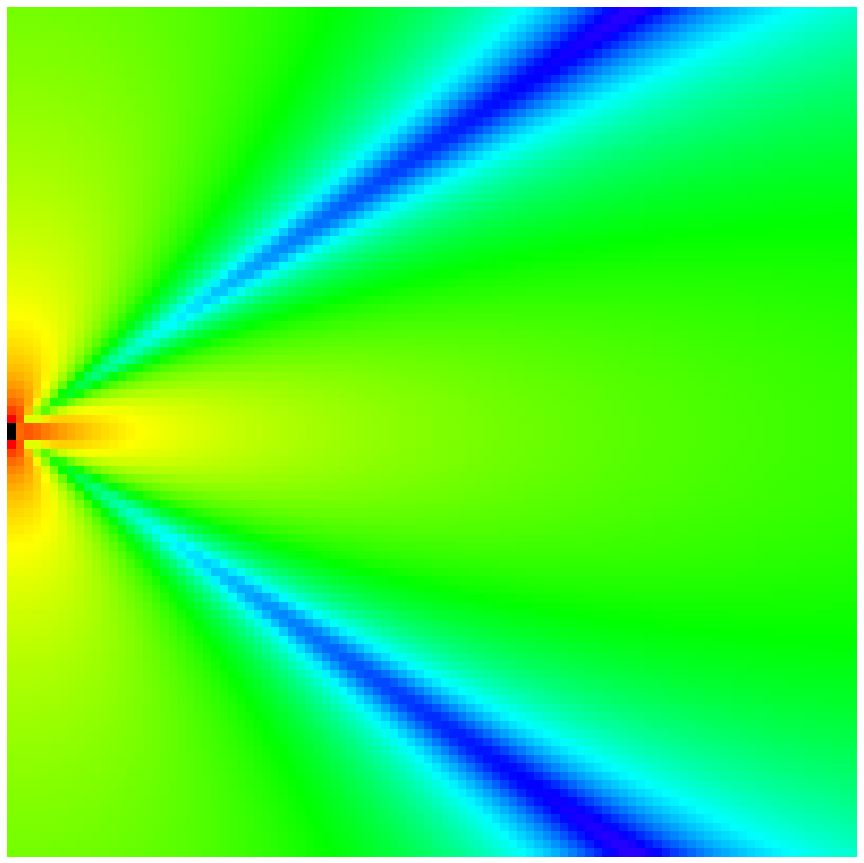

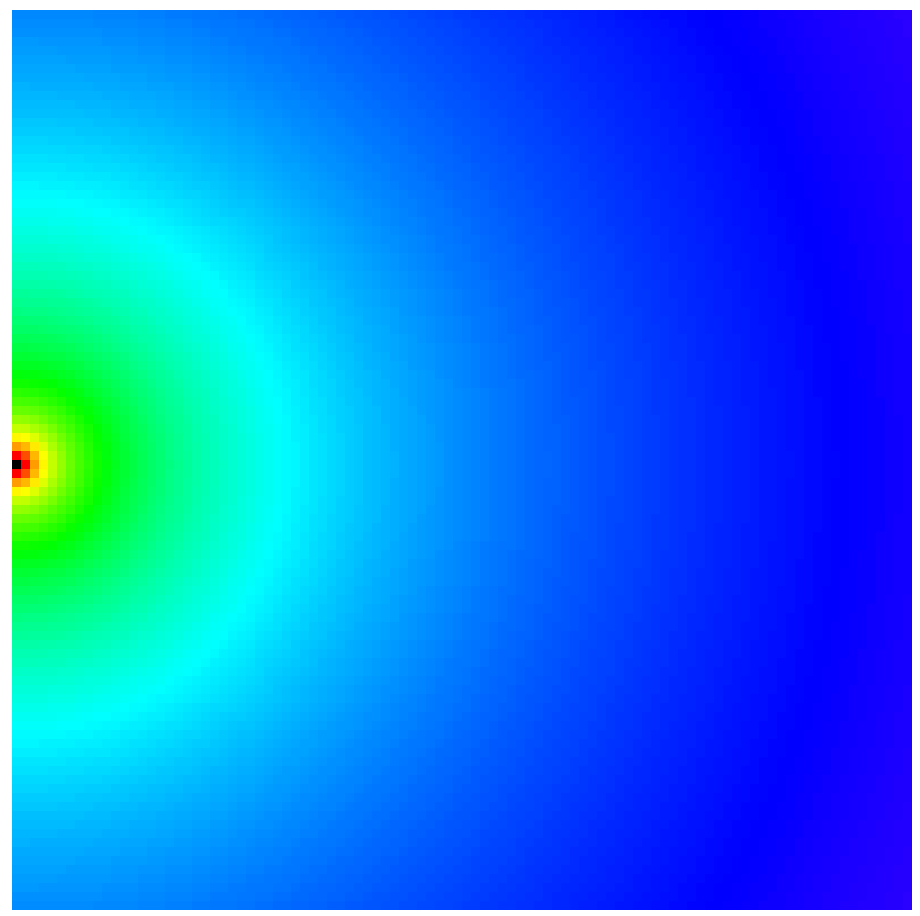

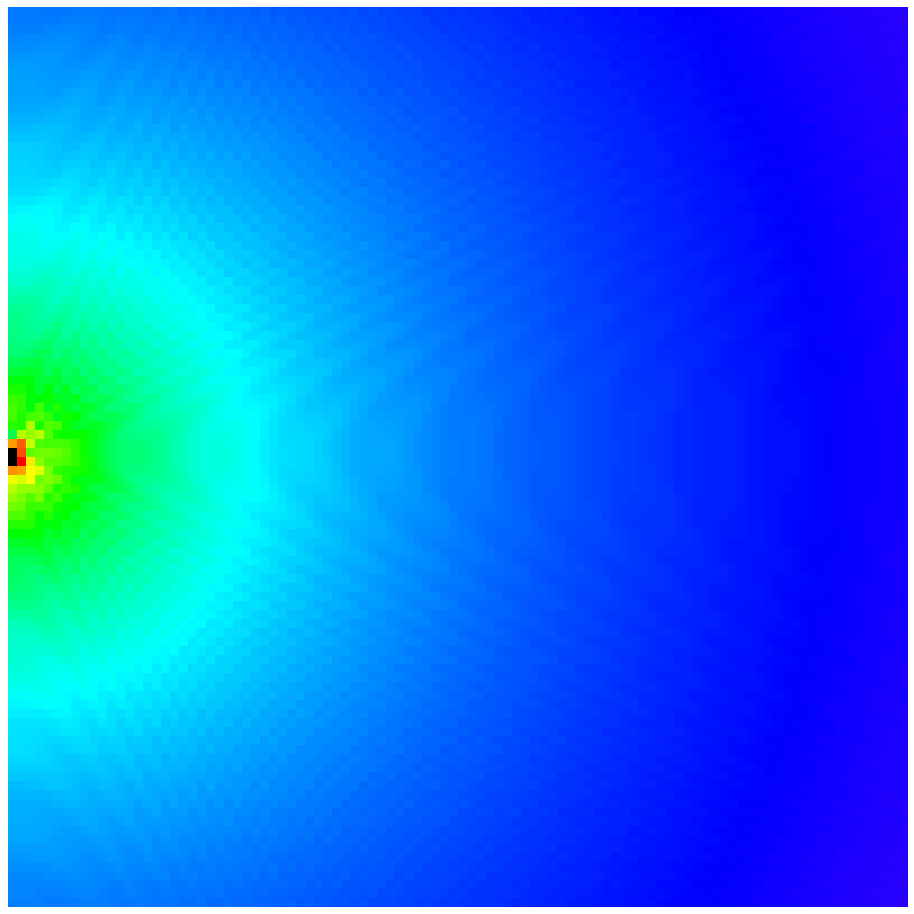

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

My dog LOVES it when we play with the hose. She gets soaked which is the BEST, and she gets a drink, which is the BEST, and she gets to pounce and jump, which are also the BEST.

I like it when we play with the hose, because it gets me thinking about audio nerdiferousness. (“Nerdiferousness” is definitely a word, because I just made it up.)

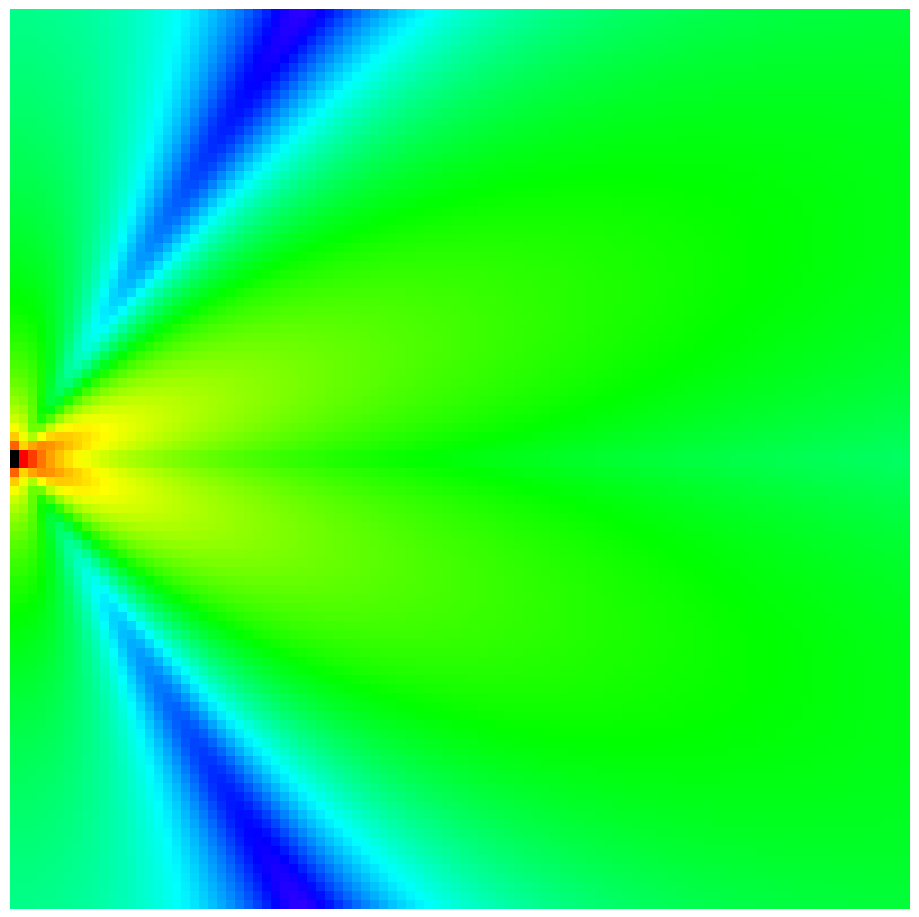

Making the hose fun requires a nozzle, and this is similar to loudspeakers for live music. Making live-audio speakers fun also requires a nozzle (a horn) for the high frequencies, at least for the conventional enclosures that most of us use. As usual, it all comes down to an impedance problem.

The hose isn’t very much fun with the nozzle removed, because the pressure delivered to the dog is too low. There’s no lack of motive force to get the water out of the hose, and indeed, running without the nozzle gets a greater volume of water to transfer out of the hose and into the environment on a second-per-second basis. The thing ruining all the joy is that the hose output impedance is quite high, and the input impedance of the world outside the hose is very low. That is, the tubing has a pretty small cross-section in the grand scheme of things, and that cross-section very suddenly turns into an effectively infinite cross-section when the hose ends and the rest of the world begins. Without a tremendous amount of pressure behind the water – far more than the municipal supply can provide – the water merely tumbles out the end and doesn’t travel very far.

It’s entirely similar to an electrical pathway. Motive force (voltage) or pressure drops as flow travels across paths offering resistance, with the motive force dropping to zero at the end of the circuit. If a high-resistance pathway is followed by a low-resistance pathway, more of the voltage is lost across the high-resistance component. The bigger the difference, the larger the drop. So, if a high-impedance hose directly couples to the very, very, VERY low impedance of the world around it, the pressure drop between those two environments is basically all the pressure available.

The point of the nozzle, then, is to increase the apparent impedance between the hose-end and the world. It does this by restricting the output flow. The force behind the water doesn’t change, but the apparent pressure is greatly increased due to that force being applied over a very small area. So, if we’re willing to accept coverage area, we can get a high-pressure jet that the dog finds highly amusing.

It’s very similar with horns and loudspeakers. A loudspeaker driver, particularly a high-frequency driver, can make plenty of pressure. HF driver’s are also high-impedance devices from an acoustical standpoint. They’re much “stiffer” than air. The bugaboo, then, is that the world beyond that HF driver is very low impedance. The available energy flat out transfers poorly when there’s a sudden transition between the driver and the environment. Just like the hose, if we’re willing to accept a smaller coverage area, we can create a better energy transfer situation. The horn changes from a restricted space to a less restricted space over a certain amount of travel, which means that the environment the driver directly couples to is much higher in impedance than an immediate change from itself to free-air. It’s a much more efficient use of the available energy. The gradual transition results in rather more pressure transfer from the horn to the outside world in the first place.