I know that Joe Bonamassa’s opinion piece for Guitar.com, When Did The Electric Guitar Become Such A Pariah? has a rhetorical question for a title. I also know that Mr. Bonamassa sits astride the world of music as would a god, whereas I…definitely don’t do that. I’m going to answer anyway, though, because I’m opinionated as fondue and I have a website.

So there.

Electric guitar became a pariah with audio engineers for a whole raft of reasons, but here are two that stand out to me right now:

- A significant number of players haven’t literally or metaphorically read the final paragraph of Joe’s op-ed, where playing appropriately for the gig is mentioned.

- A large number of audio humans have never figured out that their job is to work with the noise in the room, rather than trying to totally reshape the noise in the room.

I’m going to start with #2, because those are “my people” in the most direct sense.

Many of my people come from a studio background. In a modern setting, a studio engineer is often expected and encouraged to use a dizzying array of tools for the purpose of changing things. “I want to get that sound,” says a musician, and the engineer sets about a process of converting one noise into a different noise. Either that, or it’s “I want to get that sound” on the part of the engineer – but what happens is the same. Sculpting. Tweaks. Their very favorite EQ plugin. Dynamics tricks. Precise level setting so that the guitar pulls into a parking place within the mix that is “just so.” This is made feasible by the broken loop of the studio setting. The original acoustical event ends very quickly, and stops being a contributor to what the engineer has to work with. Instead, they work with reproductions of that event, reproductions where the control over their intensity is absolute for every practical purpose.

And then, this fastidious, picky molder of aural clay finds themselves behind a live-audio mixing desk. They’ve been put in that position because they are a “killer sound engineer,” and to get “killer sound” at a live gig you want to have a “killer sound engineer!” They got a “killer sound” on the record. It was a great mix. So, of course, they just need to do the same things at the gig, and the result will be the same, right? RIGHT?

But, of course, this overlooks the problem that mixing a real band, in a real room, in real time, for a real audience is a different sub-discipline of audio engineering. The vocabulary and tools are essentially the same; The process is different.

The problem being overlooked, then, precipitates a new problem. The engineer wants to get control over what’s going on in the room. To do that, the thing they have direct management of – the PA – has to be much, much louder than the acoustical contribution of the band. So, if the guitar player(s) are already loud, then the PA has to be really loud…and if the guitar players start at !@#$%^ LOUD, then the PA has to be REALLY !@#$%^ LOUD. This often does not go over well with audiences and venue managers, so a new solution was devised by the engineer:

Make the band quieter.

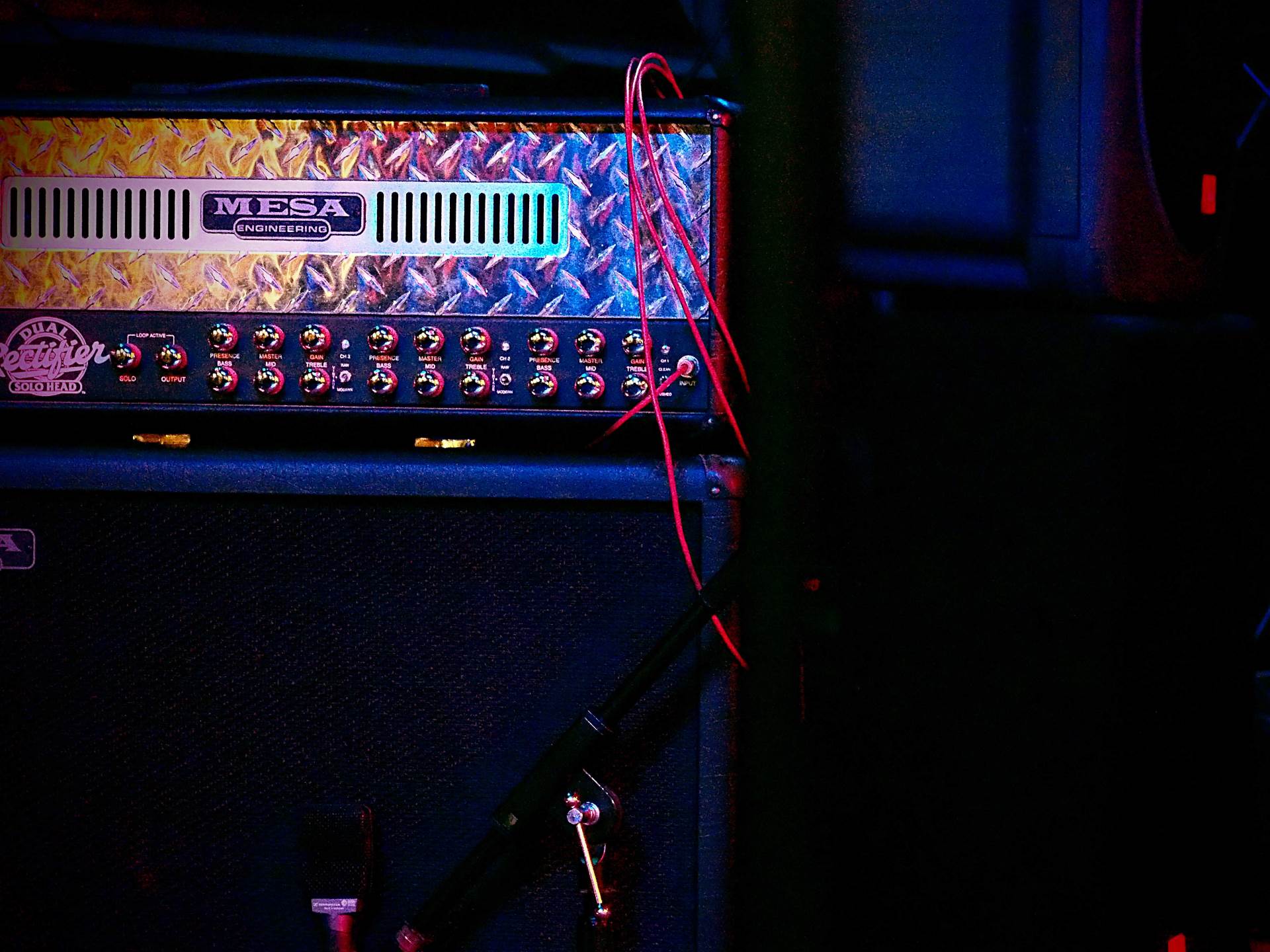

And it’s much easier to make guitarists quieter than drummers (who are often culprits in the too loud spectrum), due to how the guitarist’s production of sonic energy is generally contained within a singular piece of technology that is divorced from the player’s own physical being, a thing known as a guitar amplifier. In any case, the discipline of working with – and in extreme cases, around – the noise of the band is not on the radar, so the electric guitar becomes the focus of the “get control over this thing” efforts.

The last paragraph above feeds into the first thoughts regarding the players. Guitar players have a focus on the technology of their instrument that I think is actually comparable to other serious musicians, but with one differentiating caveat: Mysticism.

What I mean is that I have yet to meet a percussionist who demonstrates a mentality where – say – maple shells are an intrinsic factor in rock and roll “being right”. They may be important, even critically important at a practical level, but they aren’t intrinsic to the soul of the music. With guitar players, there’s a quite common (though not universal) sense of near-religious reverence towards the technology stack that produces the sounds. It goes beyond practicality and crosses into the sacred.

The trouble comes from the genre-defining, mystical tones being a byproduct of solutions for conundrums that don’t exist anymore, or don’t exist for that particular player. Amps that could produce clean tones at high SPL to compete with big brass, and that were found to have very nifty distortion characteristics at even higher volumes. Walls of amplification necessary for the coverage of very large audiences when PA systems were meant almost exclusively for vocals.

The mysticism being built on both that kind of sound’s distortion components, and the overall experience of that sound’s absolute SPL creates an unbending desire to achieve that result. The player says, “if it doesn’t sound like this, it isn’t right,” and everybody else (including the audience) has to keep up. The concept of playing to the gig doesn’t register, or it doesn’t hold enough weight as a priority.

Now put the above two sections together, and you have the ingredients for electric guitar becoming a pariah. A problem-creature that must be fixed.

And with the technology existing to downsize and de-volume the electric guitar with relative ease, the pressure to do so is quite high. Some folks have had great results with doing so, and others (like Joe Bonamassa) have not enjoyed the ride. If you want a universal fix that will make everybody happy, you’re probably out of luck…at least until every audio engineer learns to work with the sound they’ve already got, and until every guitar player can re-jigger their expectations on a show-by-show basis.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.