Mysterious distortion just might be caused by a dying battery.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.If you know a little German (and who doesn’t, what with all the WWII movies out these days) you might get the pun in the picture up there. If you’re mystified, well, let’s just say that Google is your friend.

Anyway.

Picture this: You’re the sound craftsperson for a themed, “acoustic-music” gig hosted by JT Draper. The middle act features a player who wields an upright bass. Part of his kit is a piezo-plus-mic pickup system that uses a specialized, battery-powered preamp. You get started with line-check and things seem okay. The bass seems “twangy” through the PA, but you don’t have a lot of time to think about it. The first song gets played, and you feel like there isn’t enough of that upright. You get on the gas with the appropriate channel, but it doesn’t seem to be helping much.

You solo the channel.

The bass is heavily distorted.

So, you run up to the stage after the song, and have a quick conference with the player. The prime suspect is the battery, but changing it out requires a screwdriver and a few minutes. In the end, the very fastest thing to do is to grab an unused instrument mic, point it at the bass, and dive back in.

But why would the prime suspect be the battery?

Jump Off The Swing

To be clear, you can get the sound of distortion from a bad connection. A partial short can really make some interesting (also, evil and vicious) noises. Get voltage not quite going where it’s supposed to, and electronics can become rather unhappy.

If a bad connection seems unlikely, however, the “classic” precipitating factor for harmonic distortion becomes the culprit: Something is being asked to “swing” more voltage than its design allows. When this occurs, the overloaded device produces spurious tones that are multiples of the frequencies present in the input signal – harmonics, in other words. As the device is driven harder and harder, its peak voltage remains fixed, but the RMS voltage rises. The distortion components become more and more prevalent in the output signal, raising its average level.

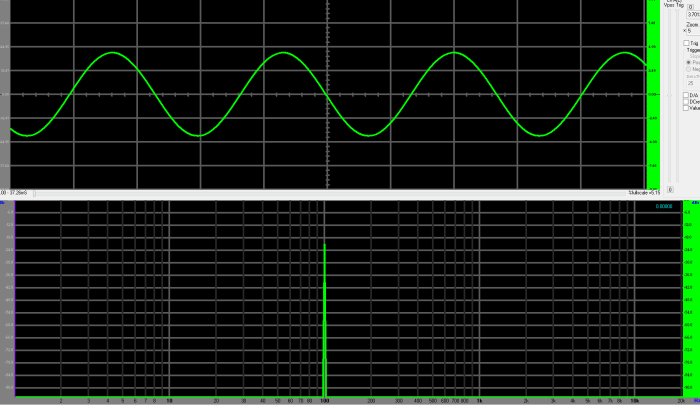

For example, here’s an analysis view of an undistorted 100 Hz tone.

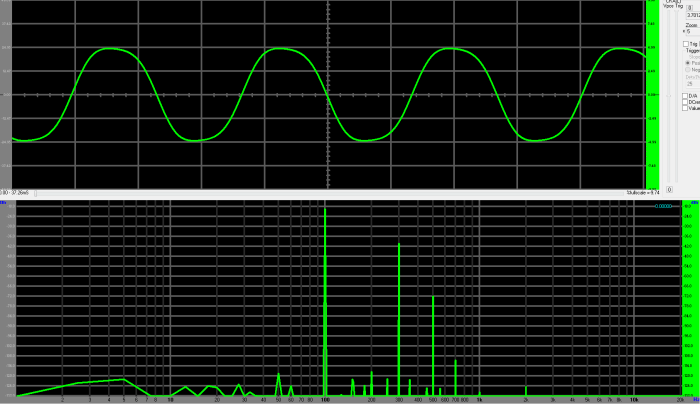

Now, I’ll simulate what happens when an attempt is made to drive that signal to a voltage that a device can’t actually swing at its outputs.

You can begin to see how the waveform is flattening out and gaining more “area under the curve.” Harmonics are also clearly visible in the FFT display.

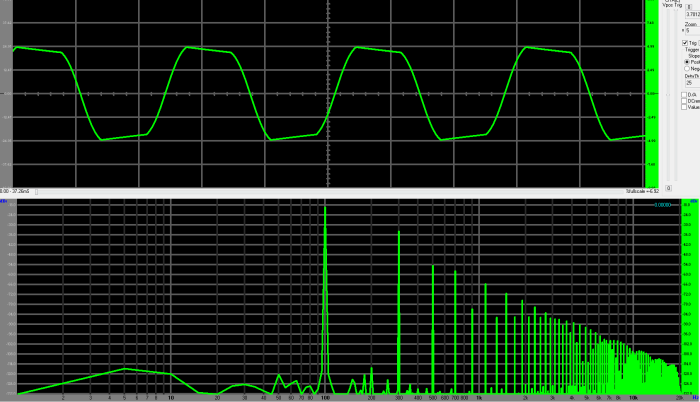

Dial things up a bit more, and…

The average level of the signal continues to climb, while the peak is stuck at its maximum. Harmonics all the way up to the end of the audible range are clearly visible on the analyzer.

What does a dying battery have to do with this? Well…

Insufficient Supply For The Demand

If you’ve got yourself an active electronic circuit, i.e., a circuit that requires a steady “supply” voltage and not just the input signal in order to operate, there’s a very important limitation in play: Without some sort of additional component or device, you can NOT swing more voltage at the outputs than is available from the supply. If you find a way to safely boost the supply, that’s fine – but the boosted supply is now simply the supply.

If the supply voltage drops, then the amount of voltage you can cleanly swing will also drop. (Makes sense, right?)

So, if you’re rolling along happily, producing an output voltage that’s just below the maximum, what happens if the supply suddenly decreases? Well, if the available voltage is below what you’re trying to produce, you’re going to get distortion. How much distortion you get is dependent upon how much your supply has been reduced. For audio gear that gets connected to “mains” power, we (usually) don’t have to worry very much about the supply changing dramatically and unexpectedly. Batteries are a different story.

As a battery gets used, its voltage drops. At a certain point, that voltage drop can result in a supply that’s too low to accurately pass a signal with the desired amount of gain applied. Combine this with the tendency (as far as I’m aware) for batteries to discharge smoothly for a long while…then suddenly have their voltage “drop off a cliff,” and you’ve got a recipe for distortion that rears up rather quickly.

So, if a battery-powered device is suddenly producing a lot of distortion, a prime suspect is the death of that power cell. You DO need to eliminate the possibility of a connection problem, and you also need to be careful to check your gain structure. Some instrument preamps’ output levels can hammer the tar out of an un-padded console mic pre. If you’ve “controlled” for those two issues, though, it’s probably time to try a new battery.