Trust your ears – but verify.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.It might be that I just don’t want to remember who it was, but a famous engineer once became rather peeved. His occasion to be irritated arose when a forum participant had the temerity to load one of the famous engineer’s tracks into a DAW and look at the waveform. The forum participant (not me) was actually rather complimentary, saying that the track LOOKED very compressed, but didn’t SOUND crushed at all.

This ignited a mini-rant from the famous guy, where he pointedly claimed that the sound was all that mattered, and he wasn’t interested in criticism from “engin-eyes.” (You know, because audio humans are supposed to be “engine-ears.”)

To be fair, the famous engineer hadn’t flown into anything that would pass as a “vicious, violent rage,” but the relative ferocity of his response was a bit stunning to me. I was also rather put off by his apparent philosophy that the craft of audio has no need of being informed by senses other than hearing.

Now, let’s be fair. The famous engineer in question is known for a reason. He’s had a much more monetarily successful career than I have. He’s done excellent work, and is probably still continuing to do excellent work at the very moment of this writing. He’s entitled to his opinions and philosophies.

But I am also entitled to mine, and in regards to this topic, here’s what I think:

The idea that an audio professional must rely solely upon their sense of hearing when performing their craft is, quite simply, a bogus “purity standard.” It gets in the way of people’s best work being done, and is therefore an inappropriate restriction in an environment that DEMANDS that the best work be done.

Ears Are Truthful. Brains Are Liars.

Your hearing mechanism, insofar as it works properly, is entirely trustworthy. A sound pressure wave enters your ear, bounces your tympanic membrane around, and ultimately causes some cilia deep in your ear to fire electrical signals down your auditory nerve. To the extent that I understand it all, this process is functionally deterministic – for any given input, you will get the same output until the system changes. Ears are dispassionate detectors of aural events.

The problem with ears is that they are hooked up to a computer (your brain) which can perform very sophisticated pattern matching and pattern synthesis.

That’s actually incredibly neat. It’s why you can hear a conversation in a noisy room. Your brain receives all the sound, performs realtime, high-fidelity pattern matching, tries to figure out what events correlate only to your conversation, and then passes only those events to the language center. Everything else is labeled “noise,” and left unprocessed. On the synthesis side, this remarkable ability is one reason why you can enjoy a song, even against noise or compression artifacts. You can remember enough of the hi-fi version to mentally reconstruct what’s missing, based on the pattern suggested by the input received. Your emotional connection to the tune is triggered, and it matters very little that the particular playback doesn’t sound all that great.

As I said, all that is incredibly neat.

But it’s not necessarily deterministic, because it doesn’t have to be. Your brain’s pattern matching and synthesis operations don’t have to be perfect, or 100% objective, or 100% consistent. They just have to be good enough to get by. In the end, what this means is that your brain’s interpretation of the signals sent by your ears can easily be false. Whether that falsehood is great or minor is a whole other issue, very personalized, and beyond the scope of this article.

Hearing What You See

It’s very interesting to consider what occurs when your hearing correlates with your other senses. Vision, for instance.

As an example, I’ll recall an “archetype” story from Pro Sound Web’s LAB: A system tech for a large-scale show works to fulfill the requests of the band’s live-audio engineer. The band engineer has asked that the digital console be externally “clocked” to a high-quality time reference. (In a digital system, the time reference or “wordclock” is what determines exactly when a sample is supposed to occur. A more consistent timing reference should result in more accurate audio.) The system tech dutifully connects a cable from the wordclock generator to the console. The band engineer gets some audio flowing through the system, and remarks at how much better the rig sounds now that the change had been made.

The system tech, being diplomatic, keeps quiet about the fact that the console has not yet been switched over from its internal reference. The external clock was merely attached. The console wasn’t listening to it yet. The band engineer expected to hear something different, and so his brain synthesized it for him.

(Again, this is an “archetype” story. It’s not a description of a singular event, but an overview of the functional nature of multiple events that have occurred.)

When your other senses correlate with your hearing, they influence it. When the correlation involves something subjective, such as “this cable will make everything sound better,” your brain will attempt to fulfill your expectations – especially when no “disproving” input is presented.

But what if the correlating input is objective? What then?

Calibration

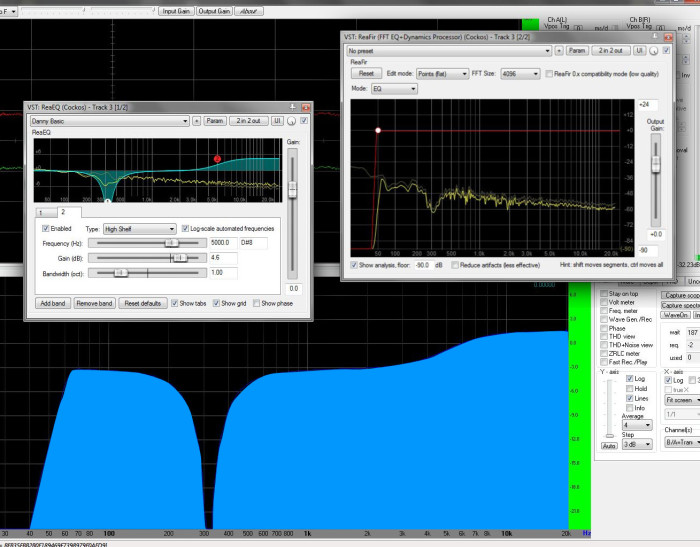

What I mean by “an objective, correlated input” is an unambiguously labeled measurement of an event, presented in the abstract. A waveform in a DAW (like I mentioned in the intro) fits this description. The timescale, “zero point,” and maximum levels are clearly identifiable. The waveform is a depiction of audio events over time, in a visual medium. It’s abstract.

In the same way, audio analyzers of various types can act as objective, correlated inputs. To the extent that their accuracy allows, they show the relative intensities of audio frequencies on an unambiguous scale. They’re also abstract. An analyzer depicts sonic information in a visual way.

When used alongside your ears, these objective measurements cause a very powerful effect: They calibrate your hearing. They allow you to attach objective, numerical information to your brain’s perception of the output from your ears.

And this makes it harder for your brain to lie to you. Not impossible, but harder.

Using measurement to confirm or deny what you think you hear is critical to doing your best work. Yes, audio-humans are involved in art, and yes, art has subjective results. However, all art is created in a universe governed by the laws of physics. The physical processes involved are objective, even if our usage of the processes is influenced by taste and preference. Measurement tools help us to better understand how our subjective decisions intersect with the objective universe, and to me, that’s really important.

If you’re wondering if this is a bit of a personal “apologetic,” you’re correct. If there’s anything I’m not, it’s a “sound ninja.” There are audio-humans who can hear a tiny bit of ringing in a system, and can instantly pinpoint that ring with 1/3rd octave accuracy – just by ear. I am not that guy. I’m very slowly getting better, but my brain lies to me like the guy who “hired” me right out of school to be an engineer for his record label. (It’s a doozy of a story…when I’m all fired up and can remember the best details, anyway.) This being the case, I will gladly correlate ANY sense with my hearing if it helps me create a better show. I will use objective analysis of audio signals whenever I think it’s appropriate, if it helps me deliver good work.

Of course the sound is the ultimate arbiter. If the objective measurement looks weird, but that’s the sound that’s right for the occasion, then the sound wins.

But aside from that, the goal is the best possible show. Denying ones-self useful tools for creating that show, based on the bogus purity standards of a few people in the industry who AREN’T EVEN THERE…well, that’s ludicrous. It’s not their show. It’s YOURS. Do what works for YOU.

Call me an “engineyes” if you like, but if looking at a meter or analyzer helps me get a better show (and maybe learn something as well), then I will do it without offering any apology.