Cleverness is only helpful if it’s applied to the right problem.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Back in October, I ran a fog machine “dry” by fixing it’s remote switch. Not directly, you understand. In an effective sense.

Here’s the story:

I switched over to an actual, honest-to-goodness continuous hazer after my old unit refused to unclog. I still had juice for the old hazer, though, and I didn’t want to just toss it out. I discovered that we had an old fogger that still worked, and the leftover haze juice was water based – thus, it would be (mostly) compatible with the fogger. I decided to take the new hazer out of service for long enough to burn off the old haze fluid.

I rigged up an extension to the fogger’s remote so that I could drive the output from FOH (Front Of House). In the process of making my extension work, I discovered that something was amiss in the remote’s switch wiring. I did some light pulling and finagling, and a proper connection was re-established.

Groovy. (Yes, that’s a shout out to “Army of Darkness,” even though you couldn’t tell.)

The fogger went back into service in time for a two-band show. The opener ended up pushing their downbeat time back about 30 – 45 minutes, but I wanted to establish some atmosphere (literally and figuratively) while we waited.

So, I hit the “Fog” button, and nothing happened. I figured that the button wiring had gotten tweaked again, so I pushed and pulled on the remote’s strain relief…hey, look! Fog! Nice.

The fog unit vented its output into a fan, and I got a pretty-okay haze effect out of the whole shebang. The hang-time on the haze wasn’t very long, though, so the stage ended up clearing in only a few minutes.

I kept hitting the button.

We got through most of the first act’s set, when I suddenly didn’t get fog anymore.

“Freakin’ button.” I thought. “I’m going to just open up the unit and twist the conductors together. It won’t be as nice as having the button, but I can still yank the extension connection if the haze gets out of control.”

And that’s exactly what I did. As the first band was getting their gear off the deck, I was unscrewing the cover on the remote and shorting the wires that would otherwise be connected to different poles on the “Fog” switch. Satisfied that I had performed a nifty little bit of “rock and roll” surgery, I got set for the main act.

The band’s first set got rolling, and I connected my remote.

No fog.

“The connection at the machine end must be bad. Oh well, I’ll fix that later.”

When I finally got up on deck and took a look at the fog machine, I realized what the problem actually was: In the process of keeping the venue hazy during walk-in and the opener, I had run the (rather small) fog tank completely dry. The remote wasn’t the problem at all.

Seriously, if the fogger had been a car, I would have just tried to fix the issue of not having any gas by tearing down and rebuilding the steering column. Whoops.

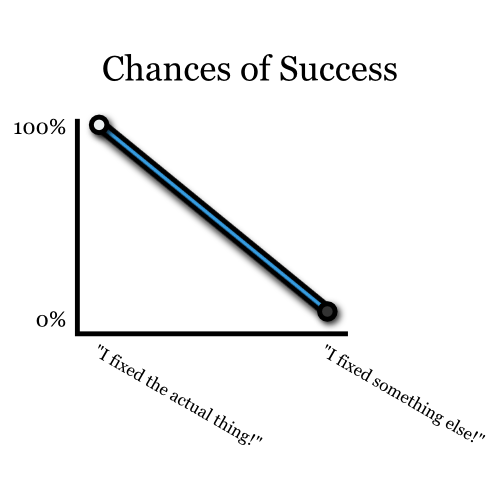

If Fixing A Problem Doesn’t Fix THE Problem, You’ve Fixed The Wrong Problem

I had just been bitten by what some folks call “The Rusty Halo Effect.” A rusty halo is a sort of mental designation that we humans give to things that have caused us trouble in the past. If a person, piece of gear, venue, component, or really anything has been a point of failure before, we tend to assume that the same thing will be the point of failure again. This can actually be quite helpful, because we can build and maintain an internal list of “bits to check if you’re having problems.” Being good with the list can make you look like a fix-it ninja…

…but assuming that your list is complete can cause you to miss different causes for similar problems.

I’ll go so far as to say that most of my really embarrassing audio problems in the last few years have been due to “Fixing The Wrong Thing,” or “Misdiagnosing The Problem.” Not so long ago, I was soundchecking a drummer who wanted a lot of the kit in the drumfill. We were getting everything dialed up, and I had taken a stab at getting some levels set on the sends from the drum mics. We started to really work on the kick sound, and when we got it to the right point we also found the point where feedback became a problem.

“I’ll just notch that out,” I thought. I got into the kick mic EQ for monitor world, and starting sweeping a narrow-ish filter around the area of the big, low-frequency ring we were dealing with. Strangely, I couldn’t find the point where the filter killed the feedback.

I muted the kick mic. The feedback slowly died. Much more slowly than I would normally have expected.

This is what tipped me off to me having tried to fix the wrong problem. If a single channel is, overwhelmingly, the culprit in a feedback situation, then muting that channel should kill the feedback almost instantaneously. If that’s not the case, then you’ve muted the wrong channel.

The real problem was one of the tom mics. It was perfectly stable as long as no low-frequency acoustic energy was present, but when the drummer hit the kick there was a LOT of LF energy introduced into the tom mic, the actual tom itself, and the drumfill. All that together created an acoustical circuit that rang, and rang, and rang…right up until I muted the offending tom mic.

Silence.

I killed the appropriate frequency in the tom mic, and we were all happy campers.

So – what can be generalized from these two stories? Well:

For troubleshooting, try to maintain a skillset that includes rapid isolation of problem areas. If a suspected problem area is isolated and removed from the involved system, and the problem persists, then the problem area is actually elsewhere.

Corollary: It is very important that you strive to know EXACTLY how the individual parts of your system connect and communicate with each other.

In other words: Try not to fix the wrong thing.