Be nice, be early, and know what you’re talking about.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

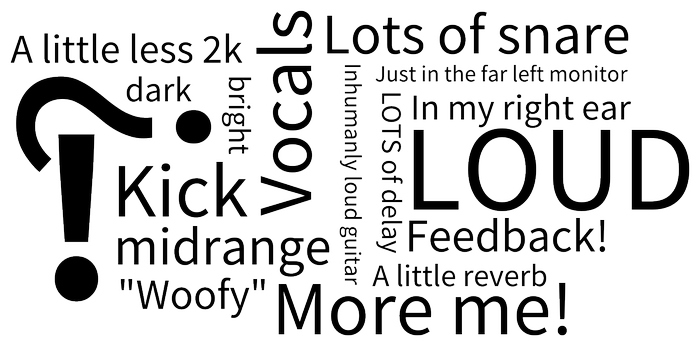

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.I was mostly done with the “wordcloud” graphic up there when I realized it was all basically about one thing. As an audio-human, most of my perception of “demanding” has to do with, well, audio. (Audio in monitor-world especially.) However, being demanding can happen across any aspect of show production. Audio, lights, staging, costumes, whatever – any area can be one where you might want to be picky.

Now, “picky,” and, “demanding” don’t really have the best connotation these days. They conjure up visions of spoiled people who can’t possibly get anything done unless everything is “just so.” You know…whiny primadonnas who are so fragile that an inconsequential mistake by catering could wreck the whole show.

But there’s honestly nothing wrong with being fastidious about the production of your show, IF you go about it the right way.

So, how do you go about being demanding in a good way? Well…

1. Be Polite

If you want to be picky, learn how to be polite. Professional show-production folks can (under the right circumstances) be inspired to move heaven and earth for you if you’re nice. Diplomatic requests in a diplomatic tone of voice – and backed up by patience and understanding – send the message that your desires come from a respect for everybody else’s craft. The unspoken connotation is that this thing is being built by a team, and you’re counting on the appropriate team member to “come through for the organization.” When that attitude comes across, it inspires respect and extra effort.

(Politeness plus enthusiasm is even more effective. Excitement and fun are infectious. If you can get people fired up and smiling, you can pull off amazing stuff.)

The flipside is acting like a brat. Depending on how much clout you have, you may still get your wish…but that wish will be granted by folks who want less and less to go the extra mile, and more and more want to just be DONE with you. You really do not want that.

Politeness is actually pretty easy. If you can stay calm, use words like “please,” “thanks,” and, “may I,” and then wait for a bit while changes are made, you’ll probably be fine.

Also, let me be clear that being diplomatic is not the same as just accepting everything silently. If you ask for a change, and you’re not sure if it’s been made, then you can always politely ask for an update or confirmation. If you handle the asking carefully, you’re much more likely to get a rational explanation of what’s going on. If it turns out that your request can’t be met, and you get a quick explanation as to why, then you’ve still come out ahead: You’ve been given a tool you can use to stay polite. Demands that aren’t reasonable stray quickly into being impolite, just by default. Becoming aware of what’s possible helps you to stay reasonable.

2. Be Early

All the politeness in the world can be quickly undone by asking for something at the wrong time. If you want to be picky, then make sure that you and everyone else have the time necessary.

There have been multiple occasions in my career when I’ve been asked to make changes on a production, and my internal thought has been “I’ve been here all day, and you couldn’t ask this until now?” Some changes, especially those that involve moving pieces of staging that are proportionally large or adding several inputs, are really not good to drop on people. A lot of prep may already have been done with the assumption that things were configured in one way. If that configuration changes, you may be inadvertently asking for your change…AND for a lot of other things to get rebuilt in a rush.

In the same vein, being detail-oriented requires time. You have to be able to identify what you don’t like, get it fixed, and then test the fix, and it’s hard to do that with just seconds to go. You want the lights to be a very specific color, and focused on very specific places? Cool! But that takes a while. You want to put together five, very specific and intricate monitor mixes? Cool! But let’s do that with three hours until “doors,” instead of three minutes.

I personally love, LOVE working on shows where we come in early and take our time. It means that we can be careful about everything, troubleshoot, get everybody what they need, and just have smiles all around. It’s a million times better than trying to muddle through a bunch of intricacy at high speed.

If you want the standing necessary to be demanding about your show, then you must give yourself (and everybody else involved) enough time to do it all properly.

3. Know What The Heck You’re Talking About

It’s really hard to be effectively fastidious if you don’t know what you’re being fastidious about. If you don’t cultivate the vocabulary and technical knowledge necessary to speak intelligently about production issues, then all you’re left with is the ability to make vague pronunciations about what you dislike. If you can’t nail down exactly what you want to change, your chances of getting it changed drop precipitously.

Also, I’ll throw it out there that not knowing what’s going on prevents you from allocating enough time to work through your show’s production. (See heading #2, above.) For instance, you don’t have to know everything there is to know about lighting, but it does help a lot if you can coarsely identify different fixtures. If you aren’t wild about a color choice, it’s good to be able to figure out if a light can change color via remote command (lots of LED fixtures and most incandescent “movers”), or if the light requires someone to manually switch a color gel (most “static” incandescents). Remote control is “cheap” in terms of time and effort, whereas a physical change is relatively difficult.

The wider point here is to acquire the ability to discuss problems in a way that facilitates helpful responses from other people. The more specific you can be, the better. Declaring that “the monitors suck” doesn’t help anyone to stop them from sucking. There are a lot of things that can suckify a monitor mix. Being able to say things like, “the guitars are too low in this wedge here” is very helpful. It tells an audio-human a lot about what isn’t right, and also (by extension) how to fix it.

Having high expectations for your show is a good thing. Getting those expectations met can often boil down to knowing what you want, having enough time available to make what you want happen, and being able to ask for what you want in a diplomatic way.