“Clean sound” has to do with more than just volume. Where that volume goes is also important.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.So – you might be wondering what that picture of V-drum cymbals has to do with all this. I’ll gladly tell you.

Just a couple of weeks ago, the band Sake Shot was playing at my regular gig. They were the opening act, and the drummer decided that the changeover would be facilitated by the simplicity and speed of just pulling his E-kit off the deck.

During Sake Shot’s set, Brian from The Daylates walked up to FOH (Front Of House) control. After saying hello, he made a single comment that caused me to do some thinking. What he said was: “The drums sound great. It’s so clean!”

He was absolutely correct, of course. The drums were very clear, and highly separated from the other sources on stage. If the sound of the drums had been a photograph, the image would have been razor sharp. The question was, “Why?” It wasn’t just volume. The mix was somewhat quieter than some other rock bands I’ve done, but we were definitely louder than a jazz trio playing a hotel lobby (if you get my drift). No…there were other factors in play besides how much SPL (Sound Pressure Level) was involved.

I’ll start out by putting it this way: It’s not just how much volume there is. It’s also about where that volume goes.

Let me explain.

Drums, Drums, Everywhere

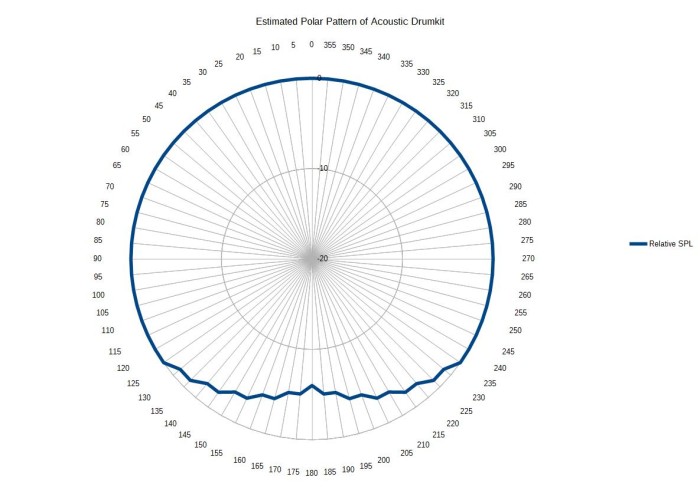

If you were to take a measurement microphone and walk around an acoustic drumkit, I’m reasonably sure that the overall plot of SPL levels would look something like this:

Behind the drummer, you might lose about 6 dB (or maybe not even that much), but overall, the drums just go everywhere. Sound POURS from the kit in all directions. In other words, the drumkit is NOT directional in any real way. This has a number of consequences:

1) Sound (and LOTS of it) travels forward from the kit, into the most sensitive part of the downstage vocal mics’ polar patterns. What’s wanted in those vocal mics is, of course, vocals. Anything that isn’t vocals that makes it into the mic is “noise,” which partially washes out the desired vocal signal.

2) The same sound that just hit the vocal mics continues forward to arrive at the ears of the audience.

3) That same sound also travels through the PA, courtesy of the vocal mics. Especially in a system that uses digital processing of some kind, latency is introduced. The sonic event being reproduced by the PA arrives slightly later than the acoustical event.

4) The sound traveling in directions other than straight towards the audience is – in a small venue – extremely likely to meet some sort of boundary. Some of these boundaries may have significant acoustical absorption qualities, and some of them may have almost no absorption at all. The boundaries that mostly act as reflectors (hard walls, hard ceilings, hard floors, etc) cause the sound to re-emit into the room, and that re-emitted sound can travel into the audience’s ears. These reflections also arrive later than the direct acoustical radiation from the kit. The reflections may exist in the closely packed, smooth wash of reverberation, or they might manifest as distinct “slaps” or “flutter.”

The upshot is that you have sonic events with multiple arrivals. One particular snare hit makes several journeys to the ears of the audience members, and what would otherwise be a nice, clean “crack” becomes smeared in time to some extent. Each drum transient gets sonically blurred, which means inter and intra-drum events become harder to discern from each other. (Inter-drum events are hits on different drums, whereas intra-drum events are the beginnings and ends of sounds produced by one hit on one drum.)

In short, the reflected sound of the drumkit partially garbles the direct sound of the kit. On top of that, the drum sound is now partially garbling the vocals.

This isn’t necessarily a disaster. Bands and techs deal with it all the time, and it’s possible to get perfectly acceptable sonics with an acoustic drumkit in a small venue. The point of this article isn’t to sell electronic drums to everybody. Even so, the effects of an acoustic kit’s sound careening around a room can’t be ignored.

Directivity Matters

Now then.

What was different enough about Sake Shot’s set to make Brian say that the sound was really clean?

It really wasn’t the SPL involved. When it came right down to it, the monitor rig and PA system were creating enough level to make the V-drums sound reasonably like a regular kit. The key was where that SPL was going…directivity, in other words.

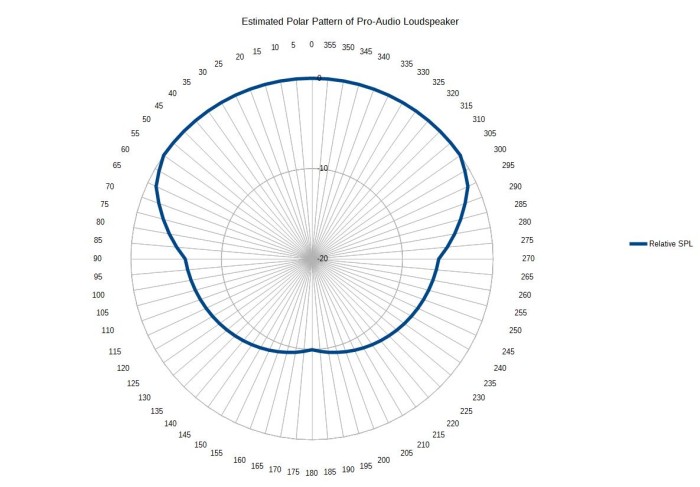

Most pro-audio loudspeakers are far more directional than a drumkit. Sure, if you walk around the back of a PA speaker, you’ll still hear something. Even so, the amount of “spill” is enormously reduced. Here’s my estimate of what the average SPL coverage of an “affordable, garden-variety” pro-audio box looks like.

This is exceptionally important in the context of my regular gig, because the upstage and stage-right walls, along with a portion of the stage ceiling, are acoustically treated. Not only do the downstage monitors fire into the parts of the vocal mic patterns that are LEAST sensitive, they also fire into a boundary which is highly absorptive. Further, the drum monitors fire into the drummer’s ears, and partially into the absorptive back wall. There’s a lot less spill that can hit the reflective boundaries in the room.

What this means is that the non-direct arrivals of the E-kit’s sounds were – relative to an acoustic kit – very low in relation to the direct arrivals from the FOH PA. Further, there was very little “wash” in the vocal mics. All this added up to a sound that was very clean and defined, because each transient from the drums had a sharply defined beginning and end. This makes it much easier for a listener to figure out where drum sounds stop, and where other things (like vocal consonants) begin. Further, the vocal mics were generally delivering a rather higher signal-to-noise ratio than they otherwise might have been, which cleaned up the vocals AND the sound of the drums.

All the different sounds from the show were doing a lot less “running into each other.”

As such, the mysteriously clean sound of the show wasn’t so mysterious after all.