…if you’re prepared, of course.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.Fog and haze are sometimes unwelcome.

It’s a shame, because I love the way that atmospheric effects make lighting “rock.” At the same time, though, I have to respect the fact that some folks just can’t handle breathing a bunch of stuff that’s been shot into the air. Also – even though I haven’t done a show in a random room for a long time – I have to respect that some venues don’t (or can’t) allow “atmo.” Some places have had bad experiences with residue and dangerously-slick dancefloors. Some places have fire alarms that trip easily, and automatically call the fire department, which is bad if there isn’t actually a fire. (Seriously, if a venue says “no fog, and no haze,” you need to listen. Your life could get very expensive in a huge hurry.)

“But we need atmospherics!” you complain. “The show isn’t the same without seeing the beams!”

Hey…I get it. Like I said up there, I’m a lover of haze. Even with the simple setup that I currently use, I love how the colors from the backlights cut diagonal lines across the stage picture. If I don’t have a specific reason to keep the hazer disabled, I’m going to run it.

So, what can you do if you’ve got a beautifully crafted, beam-filled light show all ready to go – and then someone tells you that atmospherics are out of the question?

Well, it’s time for some problem solving, and problem solving is made much easier when the bedrock principles of what you’re doing are “top of mind.” What’s the basic principle in play with your light show? In my opinion:

The Beam Has To Hit Something

I’ve talked about fog and haze before, but when I did, I was writing with the assumption that people knew why they wanted some kind of “atmo.” I didn’t really get into “first principles” with that article, though.

Light beams CAN be scattered by particles that are quite small when compared to the wavelengths of visible light. This is why the sky is blue, if you didn’t know. The general problem with this as an effect is that you need a really, really large volume of those particles to get anything visible. You also need a very intense light source…something with the luminous flux of, say, the sun. (As it turns out, unrestrained fusion reactions in space are REALLY FREAKING BRIGHT.)

Anyway, “small particle” or “Rayleigh” scattering isn’t really helpful to lighting crafts-humans. Especially in small venues (but pretty much everywhere), we don’t have a lot of air to work with, and we rarely have sunlight-comparable fixtures on hand. As such, we need “big particle” scattering in order to get anything useful. This is where fog and haze come in. Even really fine haze can be enormous when you compare the particle size to light wavelengths. If a very deep red has a wavelength of 700 nanometers, then five-micron haze is about seven times larger. The “particle-size to wavelength fraction” just gets bigger as the light wavelength increases.

The point being that the light smacks into something that’s relatively large, and scatters towards our eyes. When that happens, we get awesome light beams. Liquid sky. Aerial effects. WOOT!

That is, until someone ruins our fun by saying that they don’t want fog or haze to be used. Actually, I shouldn’t really say that, because that’s unprofessional.

See, when a band or venue tells you that they don’t want atmospherics, they probably have a good reason. What’s more, they’re coming to you as a professional and asking you to make your show work within the parameters that they need it to work in. That’s what professional production techs do: They do everything possible to get their show into the parameters that the situation presents.

If the light show needs scattering to look right, but aerial scattering has been removed from the list of allowable parameters, what have you got left?

Screens, Scrims, Banners, and Drape

This is one of those things that’s obvious when you’re reading articles on the Internet, but not so obvious when you’re deep in the throes of getting a light show built. If you’re like me, you tend to focus on your specific vision for what’s going to happen, and then forget about everything else. If a monkeywrench gets thrown, going back to the basic principles of what you’re trying to accomplish can be forgotten in the mad rush to save “the original intent.” I know. I get it.

But when somebody says “No fog or haze!” you can do yourself a great service by remembering the most basic fact of what you’re going for: Light beams that become visible due to striking an object larger than the light wavelength.

If that’s the basic requirement, then I can tell you that projection screens, scrim (material that looks opaque when front-lit, and translucent when backlit), and various kinds of drape definitely fit the bill. Hit those with the lights, and you will definitely see something. Of course, you have to be ready to modify the lighting setup to make this work…and if you’re taking a show on the road, being ready for a no-atmo situation is probably a very good idea. Yes, screens and drape aren’t as foolproof as atmospherics, due to their not being “everywhere.” Still, they’re a lot better than nothing, and can actually look quite good.

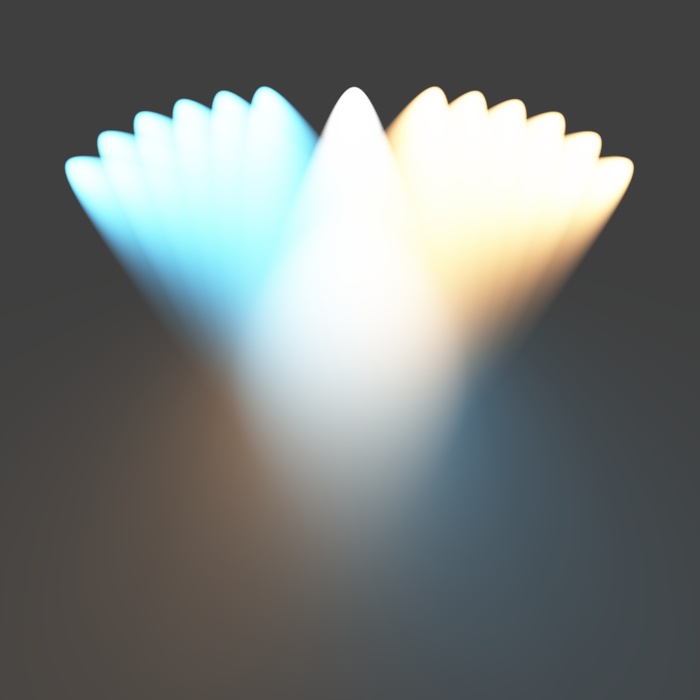

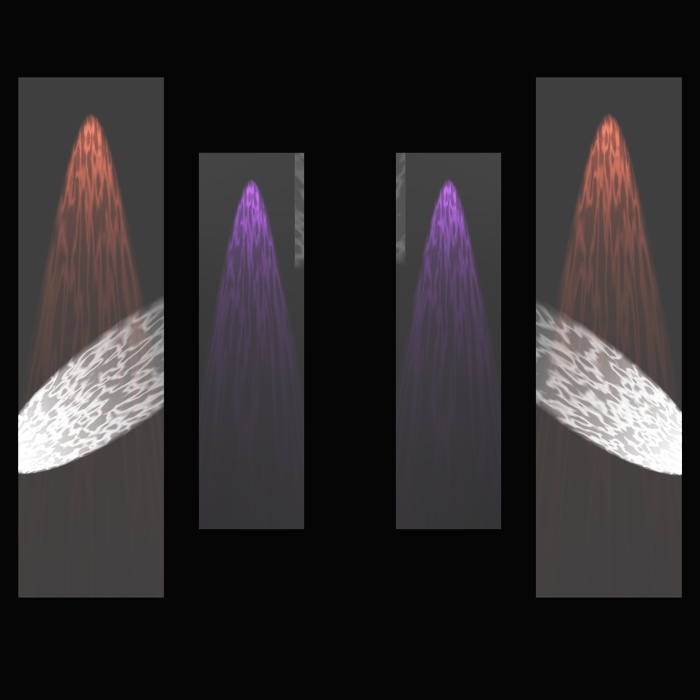

For example, here’s just one kind of kaleidoscopic effect you can get with a circular screen and a bunch of colored spots. (This is, of course, exactly what Pink Floyd – and various tribute acts – have done with “Mr. Screen.”)

In the same vein, you can also get some very nifty looks with a “full screen” behind the band and lights arranged in an arc. This is very similar to what The Australian Pink Floyd Show did for their concert at The Royal Albert Hall. (Of course, they also had fog and haze for the movers to shoot through when they weren’t aimed at the screen – but whatever.)

If you have more limited resources, you might consider “floor to whatever height” banners that you can hit.

There are lots of pointers to be had about what to use as “targets.” Obviously, honest-to-goodness movie-screen material will work nicely. Light, gauzy fabrics can also be interesting, but you have to be careful if your fixtures emit a significant amount of heat. White materials provide you with the most flexible “canvas,” but you can also get creative with other colors. Depending on your setup, you may be able to hang drape from your lighting stands. Also, make sure you’ve budgeted enough time to get everything in place and tested.

(I’m sure there are a LOT more particulars to think of, but these are the biggies that came to mind.)

The point is that being denied your atmospheric effects isn’t the end of the world. In fact, it can be an opportunity to do something different and cool.