Show promotion is an expense like any other: It shrinks or grows based on risk and reward.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Music folks of all kinds, from instrumentalists to vocalists, sitar players to sound guys, are often their own worst enemies when it comes to the business side of the…er…business. Maybe I’m just trying to flatter myself, but I don’t think it’s because we’re mentally lazy or incapable of analytical thought. No, I believe the root of the problem is that “business” is a discipline that’s separate from music and production, and so it doesn’t get developed to the same extent.

Or it doesn’t get developed at all.

As such, music humans can get bamboozled by business myths, or easily blinded by “gussied up” portrayals of how the industry works.

One of the areas that seems to be the most opaque is that of promotion. There’s no shortage of people who provide services related to it, and you can’t swing a stuffed-toy marmot without hitting someone on the Internet who dispenses advice about it. Promotion suffers from “mythology” as much as anything else I’ve encountered over the years, and I myself have blundered into believing fairy-tales.

Let’s just say that it took me until only a few years ago to realize that show promo isn’t a magical process. It’s entirely understandable to me that frustrated musicians and techs, having worked their tails off for a night that was poorly attended, will begin to say that someone “should have promoted more,” or “those people over there should have spent more money on building a buzz for the show.” There’s a belief (that I shared for a long time) that promo dollars bring people to performances in predictable ways.

It’s a false belief, but it sticks around because massive, sold-out stadium gigs get a lot of press. We make the mistake of thinking that correlation implies causation (it doesn’t), and so we figure that all that press brought a ton of people to the show (maybe it did, maybe it didn’t). We also reckon that if we did press on a similar scale, more people would come to our shows (maybe they would, maybe they wouldn’t).

Before going further, I should point out that I am still an outsider to the show-promotion world. I’ve made a good number of observations through the years, and I’ve even gained some hands-on experience with show promo and marketing in general. However, I have never been on staff with a firm that did concert marketing as its core business. As such, when it comes to things like numbers and percentages, I have no choice but to make educated guesses.

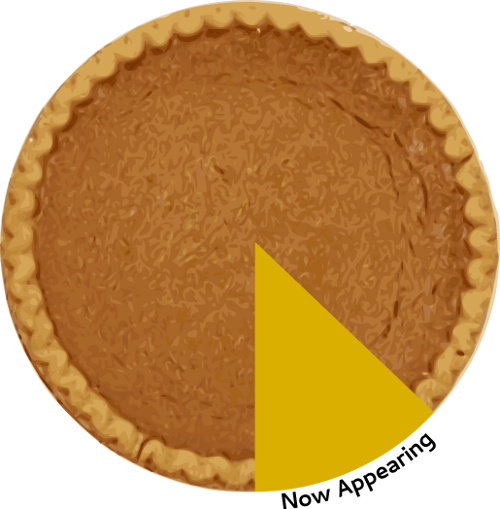

My defense for these guesses is that they seem to line up with actual realities that I’ve experienced. Those actual realities have played out in a way that suggests that promotion is a slice of the overall “pie” of show production costs, and that the slice’s absolute and proportional sizes are dependent on a number of factors.

More Pie For People Who Like The Filling

Like I said before, show promo isn’t magical. If there’s any foundational theory that the rest of this is based on, it’s that idea of non-magic. Lots of people think that promotion “creates” show attendees, but it actually doesn’t. Show promotion is just like other marketing effort, in that:

Show promo is primarily the act of informing a band’s existing, invested fanbase that an appearance by the group has been planned.

The key words above are “primarily,” “existing,” and “invested.” Sure, there are some folks that might see the promotion and get intrigued by the mere fact that something’s going on, but the main purpose is to connect with the folks who are already tuned in. Marketing ISN’T to reach the indifferent masses – it’s to reach the people who you’re very sure will go, “Shut up and take my money!” People run big, generalized campaigns for TV sets, because vast swaths of people are interested in buying them. People don’t run prime-time TV commercials for mic-preamps, because most folks don’t give a rip about ’em.

To bring this back to show-promo, though, think about a superstar, like Taylor Swift. Whether you like Taylor Swift or not, she packs stadiums. She also has a lot of promotional effort behind her. Now – here’s the question: What percentage of the people in that stadium were indifferent to Ms. Swift, yet came to the show solely because of the promo blitz?

That percentage is probably tiny. Yes, there are some folks in the crowd who are indifferent (or even dislike) Taylor Swift, but are there because a friend or family member dragged them along. Their presence is not a direct result of the promotion for the show. The fans who are invested – who are singing along, dying for a chance to see Ms. Swift up close, and are ready to buy a TON of merch – those are the people that the promotion was aimed at.

(By the way, in the above paragraphs, I’m lumping all promotion together. Expensive traditional media, essentially free social media, and middle-cost self-managed web presence are all in there.)

It makes sense, then, that promotional efforts need to be large enough to reach the audience that is expected to be listening, while not being so large that they’re wasted on people who aren’t:

The “promo” slice of the production expense pie grows in proportion to the number of people expected to be listening intently for the promotion’s message.

It might not seem like this busts the “if we only would have promoted more…” myth, but it does. You can’t promote a show into success if nobody gives a hoot about the act to start with. Taylor Swift gets a ton of big-dollar promotion because she has a ton of fans already – her act is “generally” marketable.

Pie Is Cheaper When You Make Your Own

Another myth of promotion is that more work or more expense gets better results.

Horsefeathers.

More effective and more targeted promotion gets better results. Expense and/ or effort is mutually exclusive. This is because of the previous points above – promo is about getting the news to the people who are ready to listen.

Before the era of high-speed, high-availability data and social networking, you had to use traditional media for promotions. The traditional media outlets had defacto control over who could reach an audience, and a good amount of cash was required to gain access to that audience. Part of the reason for that expense and its justification was because of the massive coverage that the media outlets had. They would quote all kinds of demographics to potential advertisers. They would supply every kind of table and chart to illustrate how many thousands or millions of people they reached, how many of those people were in certain age groups, how many bought some product last year, and all kinds of other things.

Even so, it was all a game of averages. If you spent the money to do promo via a massive outlet, you hoped that the gargantuan audience held enough interested people to make the expense worthwhile. If you weren’t sure about the mass appeal of what you were promoting, you saved money by going with more niche media. Still, all you had was a hope that someone might hear the message and respond in some way.

Particularly for artists, there was a way around this:

The fanclub.

The fanclub was a list of people who you knew were listening for information about you. There was almost no uncertainty at all – they had raised their hands and said, “I want to be informed about every concert and every release and every poster and what the band had for breakfast and…”

With this information in hand, a band could do laser-targeted promo at a very controlled cost. Postage was non-trivial, but you knew that the message was going directly to someone who wanted to hear it.

The modern fanclub is social media.

Social media isn’t perfect. To some degree, the service provider (Twitter, Facebook, G+) still exerts a certain amount of “gateway” control. At the same time, social media allows a band to promote their shows directly to an audience that has actively declared their interest. The cost involved is even less than postage, in terms of cash required to reach any individual recipient. Even better, the “post” message engagement is measurable. You can see things like retweets, likes, and shares. There’s a much more readily measurable indication of what worked and what didn’t.

The “promo” slice of the production expense pie can actually shrink as the ability to directly reach an invested audience grows.

Again, I’m going to use Taylor Swift as an example. A few days ago, she (or her management) posted to Twitter that she was going to play five shows at the O2 in London. When I looked, that tweet had 9000 favorites and 11,000 retweets. The tweet probably took someone a minute to compose. It was sent out for free – no postage required. Nine thousand people thought it was cool enough to favorite, and 11,000 people thought it was so cool that they sent it along. If each of those 11,000 people only has 10 followers, that means that the message has reached 110,000 people.

At no major cost to the artist, if at any direct cost at all.

And it’s all a lot more trackable than an ad on radio, TV, or the newspaper. I’m sure there will be promotion via those outlets for the shows, but will it be more effective than one tweet just because it was more expensive, or took more work?

I doubt it.

You Have To Save Enough Pie To Actually Eat

The final part of this discussion is the bit that’s easiest to get wrong. It’s easy to get wrong because of the myths surrounding the issues that have already been put on the table.

It’s the idea that all promotion generates more profit, so greater promotional expenses are always justified. If promo were “magic,” then this would be a safe assumption, but it isn’t, so it ain’t.

It would be great if it WAS true. Believe me, when I was a venue operator, I would have jumped at the chance to get $2.00 back for every buck that went into promotional efforts. Heck, I probably would have been on board if it was even $1.50 or $1.25 per dollar.

But, that’s not how it works.

For traditional media, there are a lot of “minimum” costs. The first minimum cost is the barrier to any entry at all – how much money does it take to get any ad space? The next minimum cost is the barrier to effectiveness. The barrier to effectiveness is the money required to get an ad with placement that catches the attention of your hoped-for audience.

The problem, then, is that cost and uncertainty of effectiveness easily overpower a promotions budget.

I don’t know about anyone else, but based on my previous experiences, I would say this:

The “promo” slice of the production expense pie should not usually exceed 25% of the expected PROFIT from the promoted event or group of events.

I printed “profit” in caps because it’s easy to confuse profit with revenue. Back when I ran my own room, my average revenue was about $74/ show. I had a killer arrangement in terms of rent, as I was essentially subsidized by New Song Presbyterian. Seven dollars from each show went out in recognition of that upkeep. I paid myself with what was left over, and took personal responsibility for most supplies, equipment, and other expenses. That amounted to about $26 per show.

The profit, then, was around $41 per event. If we round up, we could say that the maximum prudent budget for per-show promo would be $11.00.

Eleven smackers buys absolutely nothing in terms of traditional media. All of my “promo margin” saved over a year would have been enough to buy exactly one, 8-unit ad in The City Weekly. (I could have purchased multiple smaller ads, but they would have been too easy to miss.) Even if I had gotten that big, omnibus ad, would it have increased my profitability?

My guess is no, because the ad wouldn’t have been specifically targeted. I might have gotten more booking requests, but I didn’t have any trouble keeping the room busy. The risk that spending the promo money would be nothing more than vanity was very real. This leads to another rule-of-thumb:

The “promo” slice of the production expense pie isn’t worth spending if you have little confidence that the expense will grow the size of the entire pie.

The bottom line is that any production expense has to be justified in terms of making the show better, or making the show more profitable. If there’s a huge question mark in the profitability vs. promo area, then it’s far better to spend the promo budget on something else.

If cutting out a piece of a pie is supposed to get you more pie later, and it doesn’t, then you may as well have thrown that slice in the trash.