Not doing things that are pointless seems like an obvious idea, but…

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.This is going to sound off-topic, but be assured that you haven’t wandered onto the wrong site.

I promise.

Just hear me out. It’s going to take a bit, but I think you’ll get it by the end.

**********

I used to have a day-job at an SEO (Search Engine Optimization) company. If you don’t know what SEO is, then the name might lead you to believe that it’s all about making search engines work better. It isn’t. SEO should really be called “Optimizing Website FOR Search Engines,” but I guess OWFSE wasn’t as catchy as SEO. It’s the business of figuring out what helps websites to turn up earlier in search results, and then doing those things.

It’s probably one of the most bull[censored] businesses on the entire planet, as far as I can tell.

Anyway.

Things started out well, but after just a few months I realized that our product was crap. (Not to put too fine a point on it.) It wasn’t that anyone in the company wanted to produce crap and sell it. Pretty much everybody that I worked with was a “stand up” sort of person. You know – decent folks who wanted to do right by other folks.

The product was crap because the company’s business model was constrained such that we couldn’t do things for our customers that would actually matter. Our customers needed websites and marketing campaigns that set them apart from the crowd and made spending money with them as easy as possible. Those things are spendy, and require lots of time to implement well. The business model we were constrained to was “cheap and quick” – which we could have gotten away with if it was the time before the dotcom bubble popped. Unfortunately, the bubble had exploded into a slimy mess about 12 years earlier.

So, our product was crap. I spent most of my time at the company participating in the making of crap. When I truly realized just how much crap was involved, things got relatively awful and I planned my escape. (It was even worse because a number of us had ideas for fixes, ideas that were supported by our own management. However, our parent company had no real interest in letting us “pivot,” and that was that.)

But I learned a lot, and there were bright spots. One of the brightest spots was working with a product manager who was impervious to industry stupidity, had an analytical and reasonable mind, and who once uttered a sentence which has become a catchphrase for me:

“If it doesn’t work, I don’t want to do it.”

Is that not one of the most refreshing things you’ve ever heard? Seriously, it’s beautiful. Even with all the crap that was produced at that company, that phrase saved me from wading through some of the worst of it.

…and for any industry that suffers from an abundance of dung excreted from male cows, horses, or other work animals, it’s probably the thing that most needs to be said.

…and when it comes to dung, muck, crap, turds, manure, or just plain ca-ca, the music business is at least chest-deep. Heck, we might even be submerged, with the marketing and promo end of the industry about ten feet down. We need a flotation device, and being able to say “If it doesn’t work, I don’t want to do it,” is at least as good as a pair of water-wings.

The thing is, we’re reluctant to say (and embrace) something so honest, so brutally gentle and edifice-detonatingly kind.

We’ve Got To Do Stuff! Even If It’s Stupid!

I think this problem is probably at its worst in the US, although my guess is that it’s somehow rooted in the European cultures that form most of America’s behavioral bedrock. There’s this unspoken notion (that nobody would openly admit to embracing, even though we constantly embrace it by reflex) that the raw time and effort expended on something is what matters.

I’ll say that again.

We unconsciously believe that the raw time and effort expended on an endeavor is what matters.

We say that we love results, and we kinda do, but what we WORSHIP is effort – or the illusion thereof. The doing of stuff. The act of “being at work.”

In comparison, it barely matters if the end results are good for us, or anyone else. We tolerate the wasting of life, and the erosion of souls, and all manner of Sisyphean rock-pushing and sand-shoveling, because WE PUNCHED THE CLOCK TODAY, DANGIT!

If you need proof of this, look at what has become a defining factor in the ideological rock-throwing that is currently occurring in our culture. Notice a pattern? It’s all about work, and who’s doing enough of it. It’s figuring out how some people are better than other people, because of how much effort they supposedly expend. The guy who sits at the office for 12 hours a day is superior to you, you who only spend 8 hours a day in that cube. If you want to be the most important person in this culture, you need to be an active-duty Marine with two full-time jobs, who is going to college and raising three children by themselves. Your entire existence should be a grind of “doing stuff.” If you’re unhappy with your existence, or it doesn’t measure up to someone else’s, you obviously didn’t do enough stuff. Your expenditure of effort must be lacking.

I mean, do you remember school? People would do poorly on a test, and lament that they had spent [x] hours studying. Hours of their lives had been wasted on studying in a way that had just been empirically proven to be ineffective in some major aspect…yet, they would very likely do exactly the same thing again in a week or so. The issue goes deeper than this, but at just one level: Instead of spending [x] hours on an ineffective grind, why not spend, say, [.25x] hours on what actually works, and just be done?

Because, for all our love of results, we are CULTURALLY DESPERATE to justify ourselves in terms of effort.

I could go on and on and on, but I think you get it at this point.

What in blue blazes does this (and its antithesis) have to do with the music business?

Plenty.

Not Doing Worthless Crap Is The Most Practical Idea Ever

For the sake of an example, let’s take one tiny little aspect of promo: Flyering.

Markets differ, but I’m convinced that flyers (in the way bands are used to them) are generally a waste of time and trees. Even so, bands continue to arm themselves with stacks of cheap posters and tape/ staples/ whatever, and spend WAY too much time on putting up a bunch of promo that is going to be ignored.

The cure is to say, “If it doesn’t work, I don’t want to do it,” and to be granular about the whole thing.

What I mean by “granular” is that you figure out what bit of flyering does work in some way, and do that while gleefully forgetting about the rest. Getting flyers to the actual venue usually has some value. Even if none of the actual show-goers give two hoots about your night, getting that promo to the room sends a critical message to the venue operators – the message that you care about your show. In that way, those three or four posters that would go to the theater/ bar/ hall/ etc. do, in fact, work. As such, they’re worth doing for “political” reasons. The 100 or so other flyers that would go up in various places and may as well be invisible? They obviously don’t work, so why trouble yourself? Hang the four posters that actually matter, and then go rehearse (or just relax).

Also, you can take the time and money that would have been spent on 100+ cheap flyers, and pour some of that into making better the handful of posters that actually matter. Or buying some spare guitar picks, if that’s more important.

I’ll also point out that if traditional flyering does work in your locale, you should definitely do it – because it’s working.

In a larger sense, all promo obeys the rule of not doing it if it doesn’t work. Once a band or venue figures out what marketing the general public responds to (if any), it doesn’t make sense to spend money on doing more. If a few Facebook and Twitter posts have all the effect, and a bunch of spendy ads in traditional media don’t seem to do anything, why spend the money? Do the free stuff, and don’t feel like you have to justify wearing yourself (or your bank account) down to a nub. You may have to be prepared to defend yourself in some rational way, but that’s better than being broke, tired, and frustrated for no necessary reason.

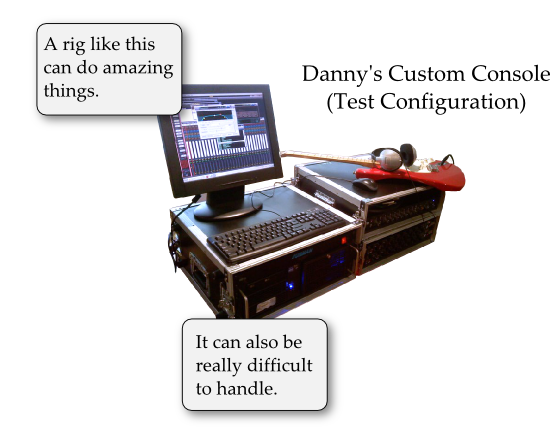

It works for gear, too. People love to buy big, expensive amplification rigs, but they haven’t been truly necessary for years. If you’re not playing to large, packed theaters and arenas with vocals-only PA systems – which is unlikely – then a huge and heavy amp isn’t getting you anything. It’s a bunch of potential that never gets used. Paying for it and lugging it around isn’t working, so you shouldn’t want to do it. Spend the money on a compact rig that sounds fantastic in context, and is cased up so it lasts forever. (And if you would need a huge rig to keep up with some other player who’s insanely loud, then at least consider doing the sensible, cheap, and effective thing…which is to fire the idiot who can’t play with the rest of the team.)

To reiterate what I mentioned about flyering, there’s always a caveat somewhere. Some things work for some people and not for others. The point is to figure out what works for YOU, and then do as much of that as is effective. Doing stuff that works for someone else (but not you) so you can get not-actually-existent “effort expenditure points” is just a waste of life.

There are examples to be had in every area of show production. To try and identify them all isn’t necessary. The point is that this is a generally applicable philosophy.

If it works, you should want to do it.

If you don’t yet know if it works, you should want to give it a try.

But…

If it doesn’t work, I don’t want to do it, and neither do you (even if you don’t realize it yet).