I was never going to buy wireless gear again. Until…

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.There is a taxonomy of falsehood. For instance, a particularly awful and hurtful falsity might be “a lie from hell.” Slightly less severe versions might be “a fib from heck,” or “a half-truth from West Jordan.” “Tall-tales from Hyrum” never really hurt anyone, as is the case for a “whopper from Utah County.”

In any case, I thought I was telling the truth when I said – to many people, repeatedly and emphatically – that I would never again put my own money into wireless audio. I was adamant. Determined. Resolute now to defend fair honor upon the glorious field of contest, I say to thee, Knights of the West, STAND!

Yeah, well, you can see how that turned out. Maybe what I said was “a fiction from Erda.” I’m not really sure.

Here’s what happened. I subcontract for a local production provider. A New Years Eve show had been on the books for quite a while, only for it to suddenly vanish in a cloud of miscommunication. The provider scrambled (thank you!) to find a show for me to do, so that I’d have a job that night (thank you!). Normally, we’d have time to handle some coordination for the show advance, but this was a situation where haste was demanded. The provider thought that I had a couple of wireless handhelds available. The show was specced, booked, and advanced. About a day and a half before downbeat, I got the input list.

A strict requirement was at least one wireless handheld. Eeeeep!

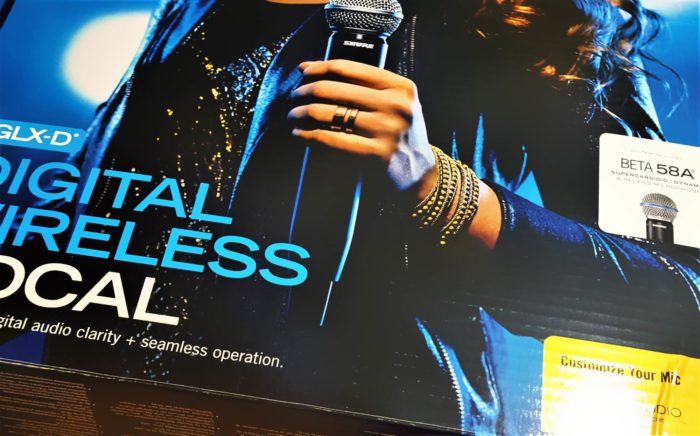

It was too late to cross-rent from one of our shared connections. My favorite place to buy or rent “right now” items was closed for inventory. I grabbed my credit card and drove to The Geometric Centroid of Strummed Instruments. (Think about it.) I was in and out in a jiffy, carrying with me a Beta58 Shure GLXD system. As much as the 2.4 Ghz band is becoming a minefield, I went with a digital system; If I was going to spend the money, I did NOT want a unit operating in a part of the spectrum that the FCC would end up auctioning or re-apportioning.

I could have gotten something significantly cheaper, but I wouldn’t have been as confident in it. My imperative was to bring good gear to the show. If I brought something from the bargain-bin, and it ended up messing the bed, that would be hard to excuse. If a better unit misbehaved, I could at least say that I did my due diligence.

In any case, the show had to go on. I’m still not a fan of wireless. I still don’t intend to add to my inventory of audio-over-airwaves devices. Even, so, you sometimes have to bend yourself around what a client needs in a short timeframe. It’s just a part of the life. Of course, after the show, my brand-new transmitter had lipstick embedded in the grille, but that’s a whole other topic…