Naturally scarce things stay valuable naturally. Artificially scarce things lose value despite all the effort involved.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

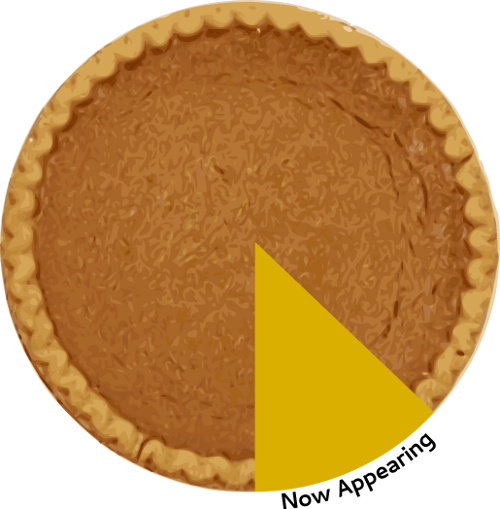

I can share this picture with any number of people, but it can’t replace the experience of actually being at a Stonefed gig.

I can share this picture with any number of people, but it can’t replace the experience of actually being at a Stonefed gig.When the whole Napster thing hit, I was one of those folks that didn’t get it.

I got all wrapped up in this idea that people were being jerks by taking music, and I wasn’t afraid to tell people how I felt about it. I had this notion that what we had was an attitude problem, and everybody’s attitude had to be fixed.

Over ten years later, I feel differently. I’ve come to realize that computing has fundamentally altered the landscape of the media, and that the alteration was by no means “unnatural.” That is, the fundamental rules of value weren’t somehow broken by us all getting high-speed, high-availability data that could transmit music. The way things are valued underwent a huge change, but not actually in a way that’s alien and incomprehensible.

Yes, there have been some very uncomfortable and unhappy consequences, but a lot of BS is also getting flushed down the toilet – and that’s a good thing. I think there’s a decent chance that these growing pains we’re experiencing are a doorway to a reality where the things that are naturally valuable, that really matter, are what will retain their value.

Things could go all topsy-turvy again at any moment, but I see the live performance as becoming more and more the locus of a musician’s ability to create value for themselves and others.

Here’s why.

Real And Artificial Scarcity

Way back when, recorded music was physically scarce. The equipment and facilities necessary to record sound were much more difficult to acquire, and the distribution media was actual, physical media. A record (the actual round thing with grooves) wasn’t something that just anybody could create on a whim. Recorded music was naturally scarce, naturally tangible, and naturally hard to reproduce without explicit permission. As a relatively scarce physical good, recorded music had a sort of natural monetary value. People who could afford recorded music bought it without a second thought, because you had to have a physical thing to play the music, and you couldn’t just make a copy for someone else.

As technology marched along, though, there was an inexorable shift. The technology required to put music-representing information into a form that machines could play back got cheaper and cheaper. There was still a good bit of scarcity, though. For instance, you could copy your favorite record to a cassette tape, but it took the entire linear play-time of the record to do so. You could make a copy for a friend, but it wasn’t a trivial process. Even with a high-speed dubbing deck, it could take a while to create the copy – and generation loss meant that the copy of the copy had a good deal more noise (and other artifacts). It was unlikely that the average Joe had a multi-copy tape deck around, so there usually weren’t many dupes to be had. The dupes also still had to be physically present for playback to occur.

So, even with consumer-writable media, recorded music was still pretty scarce.

The situation above continued to develop. We eventually gained the ability to make digital copies, which made generation loss a negligible problem. Even when the price of write-capable optical drives dropped, and the media became more affordable, there was no great tsunami of change.

And then, it became possible for regular folks to compress digital data that represented music. It also became possible for people to transfer that data between remote computers, and to do so without a fixed piece of media. (Yes, they needed network infrastructure, but the data isn’t “fixed” to the network cables. It just travels across the network media.)

Recorded music wasn’t scarce anymore.

See, the entire point of a computer is to store, change, copy, and transfer data, and to do all that as quickly as possible. Once recorded music became computer-manageable data, its scarcity was all over. You didn’t need individual pieces of physical media. Making copies was trivial, and got even more trivial. Transferring the copies was trivial, and got even more trivial.

Now then.

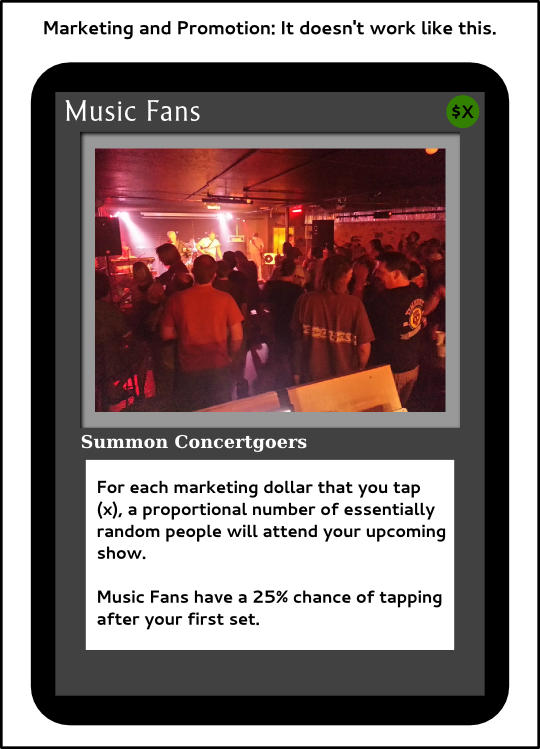

The record companies and established recording artists didn’t really like this, because their business model was and is based on the idea of recordings being scarce. As a result, the record companies hatched (and continue to hatch) all kinds of strategies to create artificial scarcity. Copy protection systems, DRM for file-based media, royalty schemes that are tailor-made for terrestrial radio but crazy for network streaming…all of it is built, even if unconsciously, around trying to keep recordings scarce.

The problem, though, is that anything you can turn into data is not scarce anymore. Fast computers and fast data have made demanding money for a piece of media obsolete. (Politely asking for money as a “thank you” for an experience is not obsolete, however.) All the copy-protection and DRM schemes in the world can’t change the simple fact that the entire globe basically runs on machines and networks which are purposefully and specifically designed to make data as un-scarce as possible.

What this means is that the intrinsic, monetary value of the data itself will drop to some minimum. The minimum may be zero, or it might not be. I don’t know.

Anyway, this is where the live show comes in.

Live Performances Are Naturally Scarce

I’m not just saying this because audio for live performance is what I do.

I’m saying this because it’s the conclusion that seems to be supported by the facts I’ve got.

As of this writing, we don’t have a way to convert an actual show into data, and that means that live shows are – digitally speaking – rare. Sure, someone can record the show on video and post the file, but you can’t make a copy of actually being there. You can’t mass-duplicate being in the crowd, and having the band right there, and being in a moment that can only happen NOW and never again. You can’t.

Now, if we ever find a way to digitize and store memories, all bets will be off. If we ever find a way to have true, full-blown, full-fidelity telepresence, the all the bets will be even more off. (If we get to that point, though, I’m betting that we’ll have made it to a completely post-scarcity society. Or a horrific dystopia. Could go either way, I guess.)

The point is still that we haven’t yet found a way to get realtime, ephemeral experiences into a form that’s trivially copied and shared. Thus, the immediate and transitory reality of a live show with a live band has tremendously more intrinsic scarcity than recorded music does. Heck, it has more intrinsic scarcity than recorded music EVER had. Big record companies could stamp a lot of vinyl, but they couldn’t make copies of the actual band.

So what?

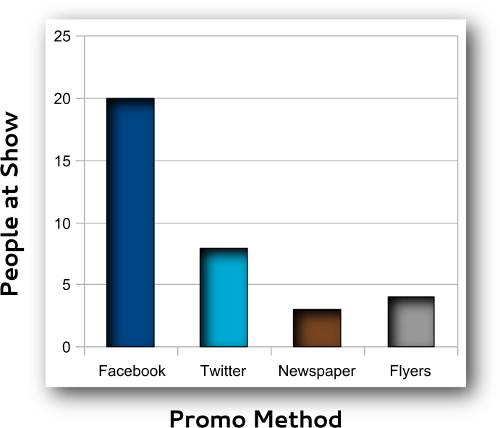

So, I say, record your music. Record it as well as you can. Shape it, polish it, and be proud of it. Even so, recognize that the recording as a saleable product in and of itself is not the concept that it used to be. The recording is a mass-marketing tool for your act, and one that you may be able to get some money from. That money, though, comes from the experience of liking and supporting the band, instead of paying to be in possession of information. The recording is data that represents how cool your songs are, just like your artist bio is data that represents how cool your band is. The purpose of this data is to be shared by as many people as possible.

Why?

Because it helps to create a lot of value around the very scarce experience of being in a room and listening to you craft an experience in real time. At least for the time being, that experience is naturally rare, and therefore precious.