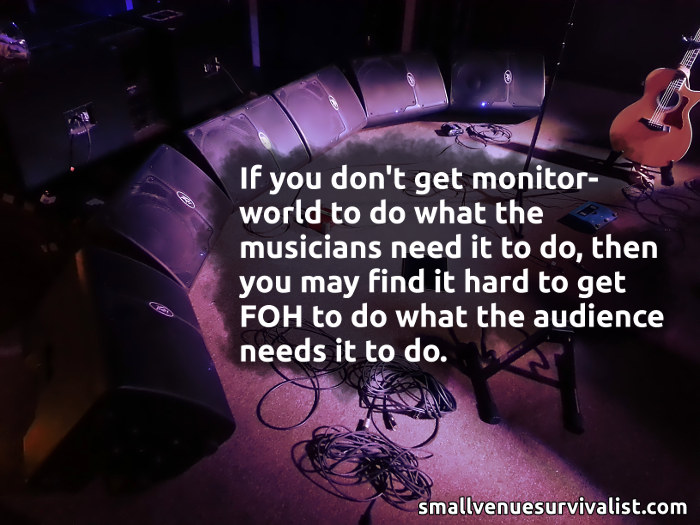

FOH and monitor world have to work together if you want the best results.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.In a small venue, there’s something that you know, even if you’re not conscious of knowing it:

The sound from the monitors on deck has an enormous effect on the sound that the audience hears. The reverse is also true. The sound from the FOH PA has an enormous effect on the sound that the musicians hear on stage.

I’m wiling to wager that there are shows that you’ve had where getting a mix put together seemed like a huge struggle. There are shows that you’ve had where – on the other hand – creating blends that made everybody happy occurred with little effort. One of the major factors in the ease or frustration of whole-show sound is “convergence.” When the needs of the folks on deck manage to converge with the needs of the audience, sound reinforcement gets easier. When those needs diverge, life can be quite a slog.

Incompatible Solutions

But…why would the audience’s needs and the musicians’ needs diverge?

Well, taste, for one thing.

Out front, you have an interpreter for the audience, i.e. the audio human. This person has to make choices about what the audience is going to hear, and they have to do this through the filter of their own assumptions. Yes, they can get input from the band, and yes, they will sometimes get input from the audience, but they still have to make a lot of snap decisions that are colored by their immediate perceptions.

When it comes to the sound on deck, the noise-management professional becomes more of an “executor.” The tech turns the knobs, but there can be a lot more guidance from the players. The musicians are the ones who try to get things to match their needs and tastes, and this can happen on an individual level if enough monitor mixes are available.

If the musicians’ tastes and the tech’s taste don’t line up, you’re likely to have divergent solutions. One example I can give is from quite a while ago, where a musician playing a sort of folk-rock wanted a lot of “kick” in the wedges. A LOT of kick. There was so much bass-drum material in the monitors that I had none at all out front. Even then, it was a little much. (I was actually pretty impressed at the amount of “thump” the monitor rig would deliver.) I ended up having to push the rest of the mix up around the monitor bleed, which made us just a bit louder than we really needed to be for an acoustic-rock show.

I’ve also experienced plenty of examples where we were chasing vocals and instruments around in monitor world, and I began to get the sneaky suspicion that FOH was being a hindrance. More than once, I’ve muted FOH and heard, “Yeah! That sounds good now.” (Uh oh.)

In any case, the precipitating factors differ, but the main issue remains the same: The “solutions” for the sound on stage and the sound out front are incompatible to some degree.

I say “solutions” because I really do look at live-sound as a sort of math or science “problem.” There’s an outcome that you want, and you have to work your way through a process which gets you that outcome. You identify what’s working against your desired result, find a way to counteract that issue, and then re-evaluate. Eventually, you find a solution – a mix that sounds the way you think it should.

And that’s great.

Until you have to solve for multiple solutions that don’t agree, because one solution invalidates the others.

Live Audio Is Nonlinear Math

The analogy that I think of for all this is a very parabolic one. Literally.

If you remember high school, you probably also remember something about finding “solutions” for parabolic curves. You set the function as being equal to zero, and then tried to figure out the inputs to the function that would satisfy that condition. Very often, you would get two numbers as solutions because nonlinear functions can output zero more than once.

In my mind, this is a pretty interesting metaphor for what we try to do at a show.

For the sake of brevity, let’s simplify things down so that “the sound on stage” and “the sound out front” are each a single solution. If we do that, we can look at this issue via a model which I shall dub “The Live-Sound Parabola.” The Live-Sound Parabola represents a “metaproblem” which encompasses two smaller problems. We can solve each sub-problem in isolation, but there’s a high likelihood that the metaproblem will remain unsolved. The metaproblem is that we need a good show for everyone, not just for the musicians or just for the audience.

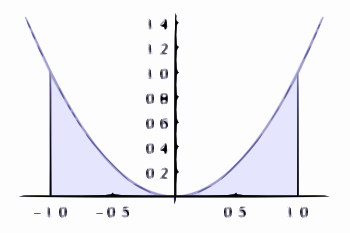

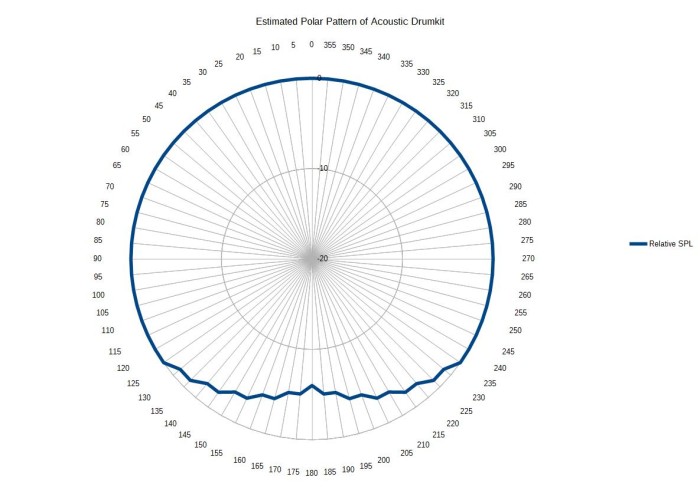

In the worst-case scenario, neither sub-problem is even close to being solved. The show is bad for everybody. Interestingly, the indication of the “badness” of the show is the area under the curve. (Integral calculus. It’s everywhere.) In other words, the integral of The Live Sound Parabola is a measure of how much the sub-solutions functionally diverge.

(Sorry about the look of the graphs. Wolfram Alpha doesn’t give you large-size graphics unless you subscribe. It’s still a really cool website, though.)

Anyway.

A fairly common outcome is that we don’t quite solve the “on deck” and “out front” problems, but instead arrive at a compromise which is imperfect – but not fatally flawed. The area between the curve and the x-axis is comparatively small.

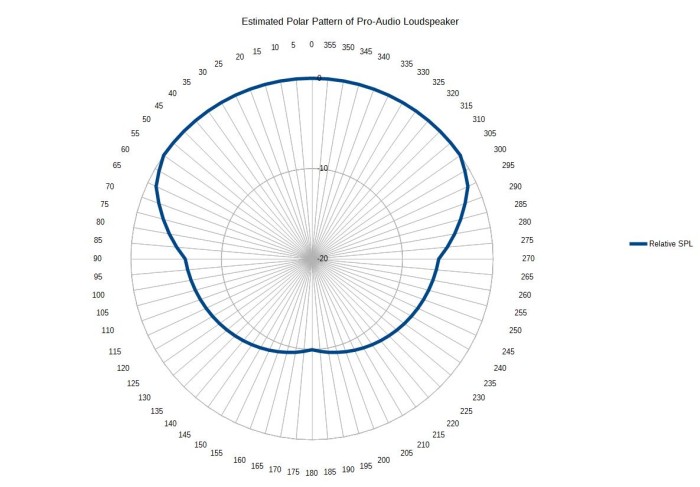

When things really go well, however, we get a convergent solution. The Live-Sound Parabola becomes equal to zero at exactly one point. Everybody gets what they want, and the divergence factor (the area under the curve) is minimized. (It’s not eliminated, but simply brought to its minimum value.)

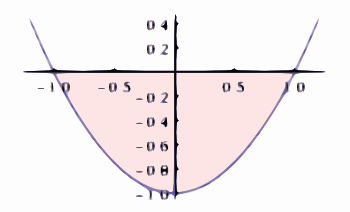

What’s interesting is that The Live Sound Parabola still works when the graph drops below zero. When it does, it’s showing a situation where two diverging solutions actually work independently. This is possible with in-ear monitors, where the solution for the musicians can be almost (if not completely) unaffected by the FOH mix. The integral still shows how much divergence exists, but in this case the divergence is merely instructive rather than problematic.

How To Converge

At this point, you may be wanting to shout, “Yeah, yeah, but what do we DO?”

I get that.

The first thing is to start out as close to convergence as possible. The importance of this is VERY high. It’s one of the reasons why I say that sounding like a band without any help from sound reinforcement is critical. It’s also why I discourage audio techs from automatically trying to reinvent everything. If the band already sounds basically right, and the audio human does only what’s necessary to transfer that “already right sound” to the audience, any divergence that occurs will tend to be minimal. Small divergence problems are simple to fix, or easy to ignore. If (on the other hand) you come out of the gate with a pronounced disagreement between the stage and FOH, you’re going to be swimming against very strong current.

Beyond that, though, you need two things: Time, and willingness to use that time for iteration.

One of my favorite things to do is to have a nice, long soundcheck where the musicians can play in the actual room. This “settling in” period is ideally started with minimal PA and minimal monitors. The band is given a chance to get themselves sorted out “acoustically,” as much as is practical. As the basic onstage sound comes together, some monitor reinforcement can be added to get things “just so.” Then, some tweaks at FOH can be applied if needed.

At that point, it’s time to evaluate how much the house and on-deck solutions are diverging. If they are indeed diverging, then some changes can be applied to either or both solutions to correct the problem. The musicians then continue to settle in for a bit, and after that you can evaluate again. You can repeat this process until everybody is satisfied, or until you run out of time.

With a seasoned band and experienced audio human, this iteration can happen very fast. It’s not instant, though, which is another reason to actually budget enough time for it to happen. Sometimes that’s not an option, and you just have to “throw and go.” However, I have definitely been in situations where bands wanted to be very particular about a complex show…after they arrived with only 30 minutes left until downbeat. It’s not that I didn’t want to do everything to help them, it’s just that there wasn’t time for everything to be done. (Production craftspersons aren’t blameless, either. There are audio techs who seem to believe that all shows can be checked in the space of five minutes, and remain conspicuously absent from the venue until five minutes is all they have. Good luck with that, I guess.)

But…

If everybody does their homework, and is willing to spend an appropriate amount of prep-time on show day, your chances of enjoying some convergent solutions are much higher.