The inspiration for today’s article comes from Resli Costabell, a corporate trainer and professional speaker. She dropped by the Small Venue Survivalist’s Facebook page a few days ago, and left a note:

‘I know you’re about playing music, and I’d also be keen to hear your tips for speakers. Not speakers as in “big black box that pours out sound.” Speakers as in “human being talking.”‘

The great thing about sound for any event, whether that event is based on music or spoken word, is that the physical principles involved don’t change. At all. Sure, there may be differences in specific application, but all the science remains as it has always been. As such, any problems that occur will tend to crop up when there’s an attempt to “Captain Kirk” a situation: “Ya can’na change the laws of physics, Cap’n!”

As I’ve said before, sound reinforcement is all about the best possible show at the lowest possible gain. The first thing we have to figure out, then, is what is critical to the success of the event, and what isn’t. I, and many other audio humans, have been witness to situations where a non-critical element becomes prioritized to the point where it wrecks the experience of the critical parts. The major culprit for public speaking?

Visual Orientation At The Expense Of Sound

This is not, in any sense, about sound craftspersons believing that they are at the center of the Universe. This is about how audio itself IS the center of the Universe at any event where the primary mode for you to impart information is speech. If your engagement with your audience is based on an auditory event (talking, that is), then everything else MUST come second to that. It’s perfectly fine for that second-place finish to be “close.” Yes, you should look professional. Yes, your slide deck should be projected as beautifully as is possible. Yes, it’s good for you to be appropriately animated on stage. Yes, you should be able to hold yourself in a comfortable way. Yes, it’s great to be able to get right up to the first row of attendees.

Yes, but…

If any of that gets in the way of you being heard clearly and comfortably, then it has to take a back seat. If it doesn’t take a back seat, then the brutal, uncompromising, feral, and downright vicious physics of sound will begin clawing and biting at your event’s success. Gain is added to mics until the system begins to noticeably destabilize. More and more equalization is applied, assuming someone is around to apply it. The sound gets more and more “hacked up.” Eventually, an unpleasant equilibrium is reached where your talk is perhaps audible, yet of an irritating tonality, tough to actually parse, and given to “ringing” in a distracting manner.

Don’t be distraught! There are things you can do to fix this.

Prioritizing Audibility

Avoid Scrimping On Audio

An alarming number of presenters will spend enormous amounts of money on signage, computer graphics, handouts, goodies, nifty chairs, nice tables, uplighting, gobo projectors, and floral arrangements…and then have almost nothing left for audio. This is an inappropriate prioritization if speaking is the core of your audience engagement.

Instead, get your sound right first. If you are having AV provided for you, go for the best system available that makes sense. You don’t need a rock-concert rig to speak to 100 people in a breakout room, but a nice mic, a flexible mixer, and some decent loudspeakers on sticks are a much better approach than some $20/ day “mini-PA” that sits on a table. You might also want to consider owning your own PA. A few bits and pieces can sometimes outperform an installed AV system. Also, it can be very nice to have a flexible “front end” if the installed coverage is great…but the controls are poor.

This point is especially important because it underpins the rest of my particulars. With all of my following concepts, I am assuming that a correctly set up and reasonably tuned PA system is being employed. A sound system that is simply inadequate can not be correctly setup or reasonably tuned to best fit your presentation. A very nice system that is not working properly is not very likely to meet your needs.

Get Help

A competent sound crew, able to listen as though they were audience members, is an enormous help to your event. If some part of the system begins to misbehave, a dedicated craftsperson can begin to act on the problem while you continue on. Small issues can be corrected quickly, without you having to think about them. This isn’t even to mention that you can do other things while the audio rig is being set up.

The alternative is that you have to do double duty. There is a point where you alone simply cannot maintain your presentation’s flow and manage audio problems in parallel. Also, it is very hard for any “set and forget” system (whether meaningfully automated or not) to compete with a knowledgeable human operator wielding an appropriate set of tools. A crew, even if it’s just one trustworthy helper, that’s dedicated to your event alone does cost a bit more. The dividends paid from that investment can be enormous, though.

Mic Choice And Technique

For the love of all that is good, please get over any hangups you have regarding blocking your face with a microphone. Microphones work best when the apparent sound pressure of your voice is VERY large when compared to the apparent sound pressure of anything else – the PA system being a valid example of “anything else.” The louder your voice is at the capsule, the less gain is needed. Making your voice the loudest thing at the mic capsule means using a directional mic and holding that mic as close to your mouth as you can. If the overall result of sounds bad because of plosives (“p” and “b” sounds which “boom” or are otherwise problematic), then change the mic position so that the airstream from your mouth is less direct. You can try parking the front of the mic on the tip of your nose, or just below your bottom lip. Be careful not to tilt the mic so that you’re effectively talking into the side of the element. The front is where a directional mic is most sensitive and sounds the best.

Yes, holding a mic in this way is going to cause some sight lines to your face to not be the best. Remember, please, that the audibility of your speech must be the winner of all arguments. I do sympathize with the needs and wants of people running video. I recommend a cordial, polite, and firm stance that three-quarter and profile shots be used if there is a concern over straight-on views.

Implicit in the first paragraph is that a handheld mic is best. A headworn unit can be okay, but it must be placed carefully. Again, the mic should be as close to your mouth as is possible, but bear in mind that many headworns are not meant to be placed directly in front of the mouth. Their “pop-and-blast” filtering is inadequate for that approach. The corner of your mouth is the target area for many of these mics. Get the mic as close to that area as you can, and then ensure that it stays where you’ve put it.

Under no circumstances should your preferred solution be a lavalier mic attached to your jacket or shirt. Holding a directional mic at the level of your chest would not be acceptable, so I have no idea why doing the same thing with an omnidirectional unit would be considered a reasonable approach. With speech, lavalier microphones are indeed useful for “after the fact” video productions. For realtime sound-reinforcement they are simply inappropriate, and if anyone disagrees with me on that point, well, I just don’t care. I will gladly enter a competition where a properly placed lavalier and a properly placed handheld are set against each other in a battle of gain-before-feedback; I am confident that the handheld will be victorious.

Vocal Power

Just a while ago I said that, “Microphones work best when the apparent sound pressure of your voice is VERY large when compared to the apparent sound pressure of anything else.” This really is THE first principle of getting things right when speaking publicly with a PA. In the same way as a powerful singer makes concert sound much easier, so too does a powerful speaker. In fact, the PA system as a whole works best when your voice’s acoustical output is a “very hot” signal.

Speak as loudly as you can without straining. Straining your voice will tire you out, maybe damage your vocal cords, and produce unpleasant overtones that irritate your audience. Without getting to that point, speak as though you had no mic and no PA system. This will help ensure that the direct sound of your voice from your mouth is the largest possible acoustical signal the microphone can encounter. You probably will not be “too loud,” but if you are (and if you’ve followed my advice about getting good gear and good help), you can very easily be turned down. Effectively reducing a system’s gain is trivial when compared to increasing the gain. Reducing overall system gain reduces “smear” from sound looping back through the system, which helps make the presentation sound better.

Where Do You Stand?

Following on some more from my “first principle,” you should seek to stand as far behind (or out of the way of) the PA system as you possibly can. The PA is not for you to hear the sound of your own voice. It is for your audience to hear you. The closer you stand to the PA loudspeakers, and the more you stand in front of them, the greater their apparent sound pressure is from the mic’s standpoint. This, of course, works against your voice being a very large signal when compared to other arrivals at the microphone.

This is another situation where sight lines may suffer a bit for some people. It depends on how the PA is deployed. As always, this is unfortunate, but your voice’s audibility must be the top priority. Your message will probably survive people not being able to see all of you at all times, but it may not survive people not being able to hear.

Acoustical Awareness

A sad fact of life is that many of our gathering spaces are built to hold many people while looking grand…and sound terrible while doing so. In the same way as musicians must be aware of how each player’s sound fits in with other sounds, so too do you have to be aware of your voice and the room. Intelligibility is key, and difficult acoustics ruin intelligibility. The sound of the room’s reverberation can easily “run over” and mask new sounds, even if it’s in a relatively subtle way. For intelligibility, you must have separation between the direct sound of your speech, and the indirect noise of previous sounds that are bouncing around the space.

To some degree, system tuning can help with this, but it’s just a “patch.” If a certain frequency area tends to build up, that area can be de-emphasized in the PA – but you have to be careful! Too much de-emphasis and it will be very obvious that a strange-sounding audio system is firing into a reverberant room. It is simply impossible to equalize one’s way completely out of an acoustical problem. Also, simply adding volume to the sound system doesn’t really help either. The audio system is a sonic emitter in the room, just like any other, and as such the room reverberation is proportional to whatever the PA is doing. A louder PA just means louder reverberation, and also a PA that’s less sonically stable. (Remember: We want the lowest possible gain.)

If PA volume isn’t the answer, then you have only one other element to work with: Time.

In a reverberant room, you MUST slow down. You have to allow for the reverberant sound to die off so that the next sonic event (a word or sentence) is separated from all the garble. Slowing down means that you may have to condenser your presentation, or allow for extra time.

There are some volume adjustments that work, but they have to come from the way you talk. Try to add a bit of emphasis to the “hard” sounds in your speech. Hard sounds act as signposts regarding where words start and end, and are critical to people figuring out what you’ve said if some of the other information is lost. Enunciating those bits mean that they stick out from other sounds, which gives intelligibility a boost.

Of course, if you can, you should pick a space with excellent acoustics for spoken word. That is, a room with a very short reverb time and very low reverb level. The larger such a room is, the more expensive it tends to be – and that loops right back around to not scrimping on audio.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

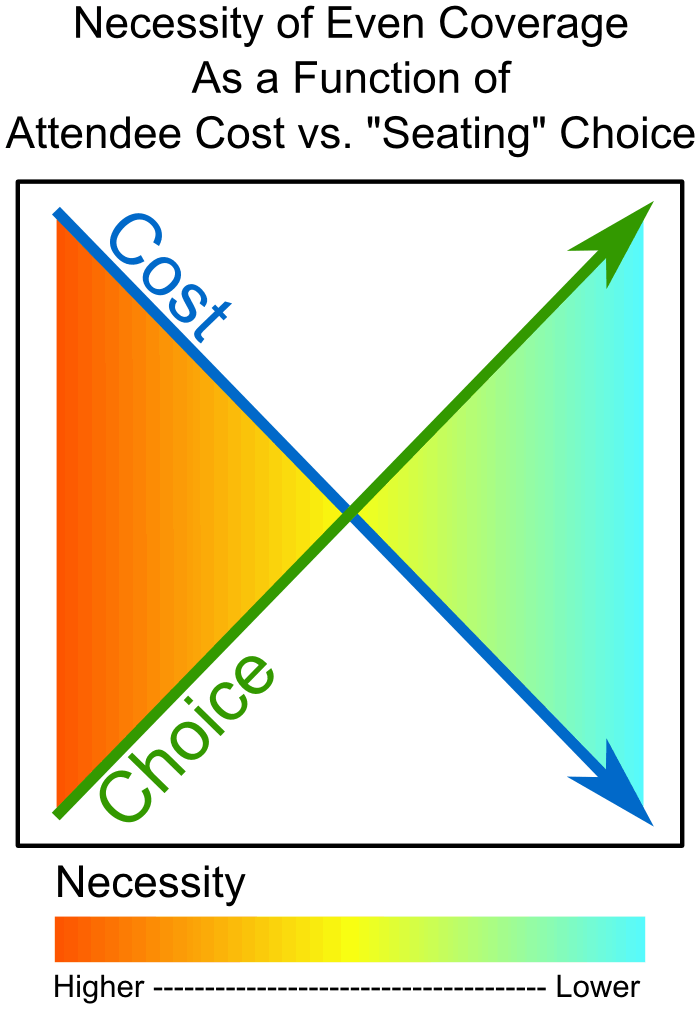

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.