Alternative Title: Why it’s so hard to get paid and get promoted.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.I’ve heard plenty of legitimate complaints about concert venues and “promoters.” I put promoters in quotes because it seems like the loudest and most legitimate complaints are aimed at the folks who create concerts by charging musicians money (directly) to play their own music. The correct word for those folks is rarely “promoter.” The appropriate nomenclature is probably more like “parasite,” or “scam artist,” or “Sauron, Lord of The Black Land” if their activities are egregious enough.

(Seriously, if someone “offers you the chance” to pay them money to play a gig where “you’ll get lots of exposure,” do yourself a favor. Walk, run, bike, drive, or charter a spaceflight that will take you FAR AWAY.)

Anyway.

I’ve also heard lots of complaints about venues and concert producers that are less legitimate. Many of these gripes have a kernel of legitimacy in them, but the blame is misdirected. I have to admit that I get a bit “hot” when I hear misdirected blame, and I also have to admit that it’s taken me a while to realize that my annoyance isn’t really helpful. The problem is education and understanding, and if I’m sitting around being mad instead of helping people to get educated…well, I’m not participating much in a solution, am I?

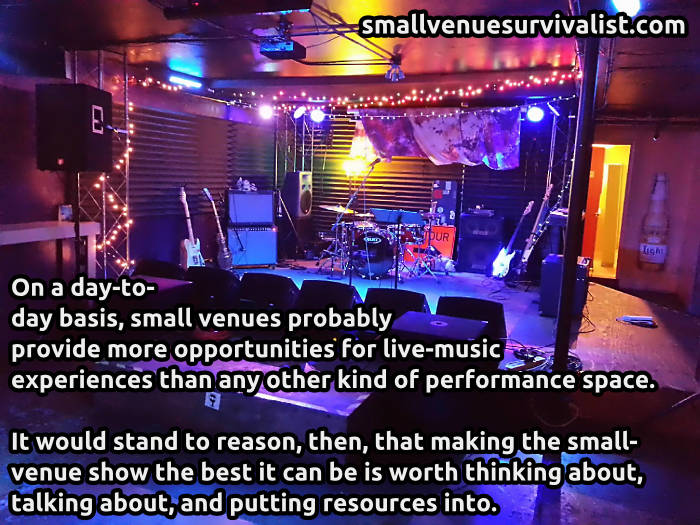

To that end, I want to present the following. It’s essentially a set of numbers that I think explains certain aspects of the economics of small venues. These economics, in turn, help to explain certain entrenched realities in what it’s like to get paid for a small-venue show, and why small-venue promotion is the way it is.

BEFORE WE START: The venue I’m presenting in this article is a “hypothetical room.” It’s what you might call a composite character, and so it doesn’t directly represent any one venue that I’ve been involved with. Certain parts of the model may apply very differently to actual, individual venues in individual locales. Please proceed with caution.

A Theoretical 200-Seater

Let’s say that there’s a certain human who really digs live music. The opportunity arises for this particular human to put together their own room. The space isn’t massive – the capacity will be about 200 people – and the spot will be “competent,” though not exactly world-class.

The plan is to put on about 160 shows per year, which is three shows per week and a handful of special events.

The first cost to the venue operator is startup. This is to cover some basic, cosmetic renovation of the space, an audio and lighting rig, and a few little things that have to be addressed to be compliant with local regulations.

Startup Cost: $30,000

Zoinks! That looks like a lot of money. It’s not so bad, though, because the plan is for it to be essentially amortized over 10 years. Divide the startup cost by the expected 1600 shows, and…

Startup Cost Per Show: $18.75

The thing with gear is that it requires maintenance. Things break, or just wear down, and so there has to be money in the budget for fixes and replacements. The decision is made to put $1000/ year into a “fixit” fund.

Maintenance Fund Cost Per Show: $6.25

The next thing to consider is the cost of leasing the space. The building is owned by a landlord who is sympathetic to the arts, and so the rent for the 4000 square-foot space is pretty darned “rock bottom.” The rate is $1/ square-foot/ month. Do a bit of math on that, and you get this:

Rent Cost Per Show: $300

On top of the rent will be the utilities required to keep the lights and gear running, the water on, the room at a comfortable temperature, and so on. Some things in the building are efficient, and some aren’t. When it all comes out, the various “monthlies” might work out to this (a wild guess on my part):

Utilities Cost Per Show: $10

The next thing needed is a show-production craftsperson. They’ll be both an audio-human and a lighting operator, and they’ll be decent enough at their job that most musicians will be happy with how things go.

Production Tech Cost Per Show: $85

The venue operator decides that some help is needed in the area of running the door, taking money, and other tasks.

Venue Helper Cost Per Show: $40

With all of this in place, the venue operator wants the acts coming through the room to get some press. The decision is made to supplement the venue’s own website and social-media promo with a print ad in the local independent. It can’t be so small that it’s easy to miss, so the decision is made to secure a 1/6th page space. The ad is black and white to save a few dollars, and each ad has all the shows for the week. The per-week cost is $360, and that works out to:

Print Promo Cost Per Show: $117

One of the final things to take into account is PRO licensing with ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC. PRO licensing is what (in theory) gets artists paid for their songs being played as covers in bars, clubs, theaters, stadiums, and whatever else. The good news for our hypothetical venue is that it’s NOT a restaurant or bar – it’s going to basically be a theater. As such, the licensing will probably be worked out to be a small portion of the gross receipts from the door. With that being the case, we’ll just ignore the licensing cost.

Now then.

You put all of this together, and the price for our theoretical room to have a night of music is this:

Total Cost To Open The Doors For A Show: $577

In other words, this venue, which I think is doing well at controlling its costs and avoiding unneeded extravagance, starts every show in several hundred dollars of debt.

Let’s Have A Show

So, let’s say that three local bands book the room for a night. They decide to charge $10 at the door to keep the show accessible to as many fans as possible.

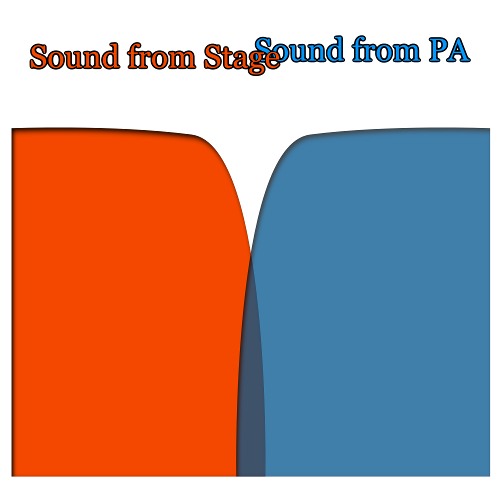

…and the turnout is pretty good! About 150 people show up, which creates a revenue figure of $1500. I don’t know about anybody else, but I don’t see that as too shabby. Here’s the thing, though: That $1500 is revenue, not profit. Profit is what’s left over after the expenses are deducted. Remember that it cost the venue $577 “just to show up.” What that means is that the raw profit for the show is $923, or just over 61% of what was taken in at the door.

You also have to remember that the person who is the venue operator is not the production human or the helper. As such, the venue operator hasn’t gotten paid yet.

If the venue operator is self-sacrificial, then they might just opt to take $100. In that case, each band would take home about $274.

If the operator wants to do things in equal shares, then the venue and each band would get $230.

If the argument is made that the venue and the bands each bore 50% of the risk of the show, then the venue would get about $461 and each band would be paid out $153 and change.

The Implications

The reality is that live music is a tough business for everybody. Even if the venue operator sacrifices themselves on the altar of getting the bands a few extra bucks, the per-band payout is hardly “2 million dollar tourbus” territory. In fact, there are some folks who, without knowledge of the sacrificial backend, would complain that they weren’t being respected as professional musicians. It’s understandable that they would have the complaint, because $274 doesn’t go very far when you split it (again) across multiple band members.

But the reality is that it isn’t an issue of respect. It’s an issue of economics.

The show outcome I concocted above was a pretty decent one. However, there are lots of shows with mediocre turnouts. Turnouts can be less than stellar for all kinds of reasons, and that leads to the particularly nasty problem of bands either not getting paid, or venues going under, or even both. For a $10/ admission show, our fictional venue has to have 58 people show up…for NOTHING MORE than to not be in debt that day.

And that’s if the bands get nothing at all for their trouble.

What’s more likely is that there’s something on the table for the bands. Maybe 50% of the ticket’s face value? Okay.

So, if 58 people show up on a $10 ticket, that means that the venue’s portion of the revenue is $290. In other words, the venue LOST $287 on doing the show. With an immediate 50% split, a combined draw of 116 people is what’s necessary for the room to stay out of debt that day.

That’s JUST to stay out of debt. The venue operator would get paid a whole $3 for that show.

…and remember that this is with print promotion factored in. Some folks are adamant that venues “should promote more,” and I can understand why that sentiment exists – but I can only be so sympathetic when the tough numbers roll in. That is, a venue operator has to ask the question: “What does promote more mean?” If it’s understood in terms of the print ad, then what if the promo effort is tripled to the equivalent of half a page in the local independent? That means that the cost for that show’s promo has risen to $351, and the venue’s revenue from the show now has to be $811 to not lose anything. With an immediate 50% split, a 200 seater selling $10 tickets has to be more than three-quarters full just to keep “above water” on the night.

(How many times have you seen a small-venue that’s below three-quarters full? Everybody’s experience is different, but I’ve seen that a lot. Even with people making special efforts at promotion and creating a show that’s an actual event, I’ve seen dismal turnouts. Dismal.)

Yes, the venue could try charging more, but it isn’t always clear how far up a ticket price can go before the cost actually ends up hurting more than helping. You can shoot yourself in the foot without even trying.

Yes, the venue could try selling concessions. However, if there’s no more room for “startup expenses,” and no more room in the space, then that’s not such an easy thing.

Yes, the venue could convert to being a bar, but the previous sentence also applies here – and it even applies more, because being a bar isn’t as trivial as selling cans of soda and bags of chips.

The uncomfortable reality is that it’s hard to get rockstar pay when the venue isn’t making rockstar pay for itself. There are some honest-to-goodness greedy-bastard venue operators out there, but there are plenty of upstanding folks who just don’t have the money to pay musicians for LearJet fuel (and the LearJet to consume it).

It’s not a lack of respect. It’s the economics of tough numbers.