Music that hits hard requires careful management of the parts that don’t hit hard.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.A few weeks ago, I had the unexpected pleasure of working with a band called “Outside Infinity.” I say that the pleasure was unexpected because I had some major concerns going into the show. Metal, as a genre, can be pretty challenging in a small space. The sheer volume can be tough (or even impossible) to work with, and the arrangements are often quite dense – which compounds the volume problem. Several instruments banging away at full-blast can make for lots of challenges when trying to differentiate each part of a mix.

Outside Infinity had none of those problems. In fact, they were a prime example of how heavy metal – or any type of music that you want to “hit hard” – actually achieves that goal. (They were so much fun to listen to that I’m pretty sure I had a stupid grin on my face for large portions of the night.) I was really impressed by the sound that they had crafted, and I started to think about it.

Why were they so much fun?

Why did they capture what I’ve loved about heavy metal in the past?

Why did their sound have what so many rock and metal bands want, but so often fail to achieve?

I think that the generalized answer to all of those questions is this: Transient impact.

The Stopping Is As Important As The Starting

There are a number of necessary elements to a really great song performed live in a really great way. The lyrics have to be interesting, of course, and a memorable melody (or overall musical theme) is required. Skipping those steps will efficiently torpedo a tune’s ability to grab and hold an audience. There’s more, though: The overall sound of the song has to keep the listener interested. It’s analogous to eating a meal that leaves you remembering the food for years. Every bite is delicious, yes, but certain bites contain an extra explosion of flavor that plays on the mouth and tongue…and then dissipates. That “taste transient” pokes out from the “steady state deliciousness” of the rest of the meal, creating an ebb and flow of special delight, anticipation, and reward.

But if that burst of flavor just continued unabated, with no steady-state to contrast it against, then the “burst” wouldn’t be attention-getting anymore. It would BE the steady-state, and would quickly become unremarkable.

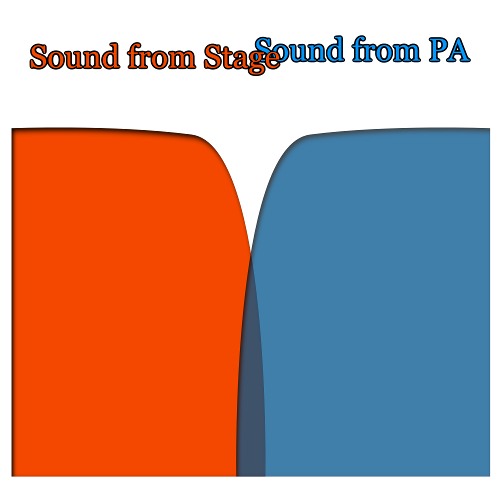

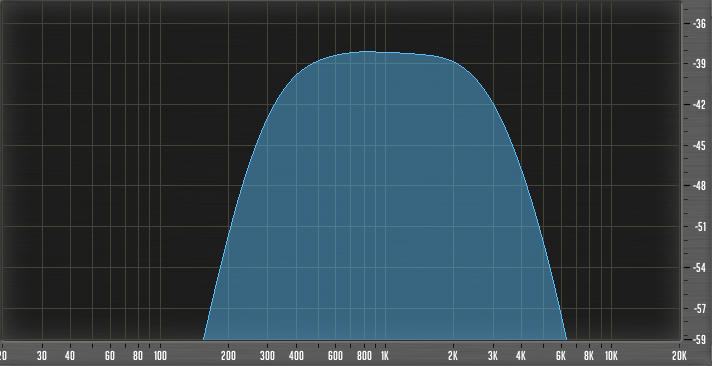

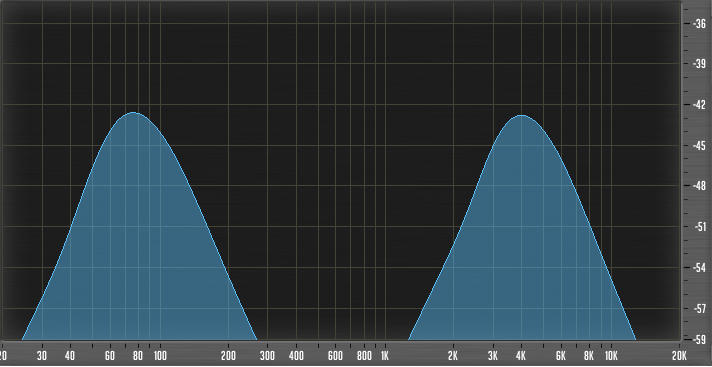

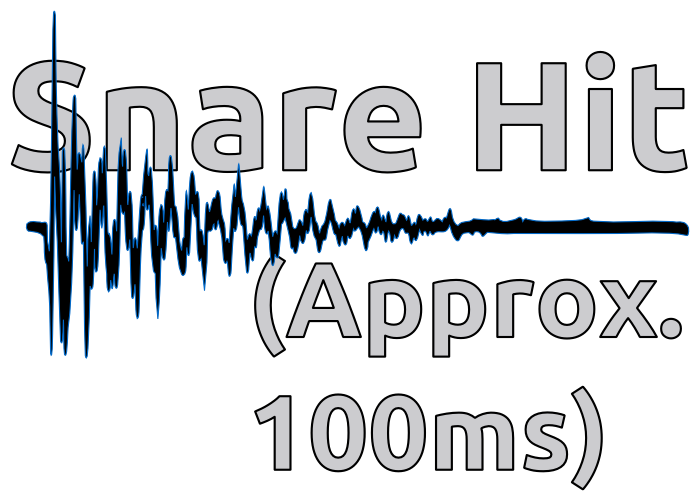

Sound behaves in a way that’s fundamentally the same. We perceive it differently, and the time-scales involved are sometimes much shorter, but the transient content is still the basis of what holds attention. Transient content is the determining factor behind the (ironically) nebulous idea of music that’s “really defined.” In music that aims to convey power and force, sounds that hit above the steady-state, and then swiftly decay are what cause the individual parts to “slam into you.” Everything just banging away at full throttle, continuously, for several minutes, has no impact. No spark of flavor. The brain starts to have trouble distinguishing the music from noise, because of the lack of anything to lock on to.

The mastery of stopping notes at the right time is what creates epic riffs. The mastery of creating a pleasing steady-state, which is then punctuated by sharp, sonic flavors, is the essence of the “thunderous” rock show.

…and because transients are all about proportionality, it is entirely possible to create a pile-driving artillery barrage of a show within the confines of a small venue. More on that later. First:

Dynamics And Articulation

Music, especially rock and metal, has a long history of breaking rules and pushing boundaries. This is what drives innovation, and it’s a good thing. However, there are certain rules that can’t truly be broken successfully. Those rules are the ones that are based in fundamentals of the physical universe and human perception.

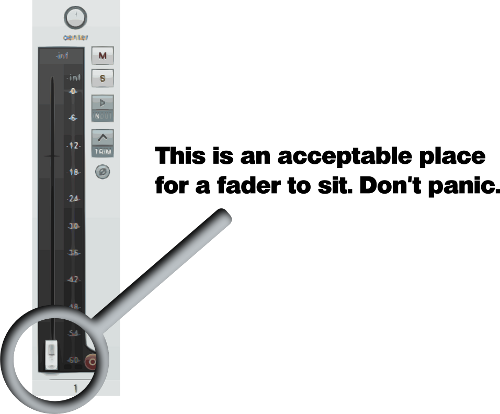

One such rule is that, for a particular musical part to seem “big,” the other parts around it must be proportionally small. There are different ways of achieving this, but it all pretty much boils down to volume. The “small” part must either be quieter across the entire audible spectrum, or quieter across the most important part of the spectrum occupied by the “big” part. Especially in the small-venue context, plenty of bands shoot themselves in the foot with this. I’ve heard too many groups that interpret the instrumental breaks of their songs as “there’s no vocal, so now all the instruments should play as loudly as they can, occupy every frequency possible, and we’ll just hope that the audio-human can crank the actual solo above all that.”

(The best bands avoid this problem by interpreting the solo instrument as being “the new vocal,” and thus they keep all the other instruments in a supporting role until it’s their turn to be in front.)

Anyway.

In music, there are lots of broad-brush ways to accomplish this necessary contrast. There are the overall dynamics of individual parts across a number of beats, and there are also the rests – where a part is silent for a time. Whether formally or informally, these contrasts can be reliably notated. It’s pretty easy to explicitly define the necessary negative space, whether by a symbol for a rest, a “pp” for being very quiet, or a scribbled note saying, “For the fingerpicked guitar part, no drums at all and everybody else turns way down.”

There’s something else, though, that’s required for mastery. It’s hard to explicitly notate. It’s articulation.

Articulation (as I see it) is the manner in which notes and chords are played. It’s a crucial part of getting transients to contrast with the rest of the music, because it involves dynamics and rests that are too short and frequent to write down…and yet have a massive effect on how other parts sound. Playing a power chord with a “micro rest” at the end can be key to getting a kick-hit to punch through. Making that kick-hit decay into silence quickly can make room for a note from the bass. Going through a run of notes where each tone is connected, but there’s a very slight volume drop just before the next sound, can make for a clean and precise solo line. The singer hitting a big note and then backing off means that they can help support that solo line without a miniature volume war erupting.

The very best bands have a reliable handle on making this all work – even if they’re not explicitly aware of what they’re doing. Their riffs are powerful and defined because the individual notes have space around them. Their drum hits are forceful and satisfying because there’s space for them to stick up above everything else – and yet the drums don’t overpower the tonal instruments, because the individual hits decay into the “steady state volume” before the tonals hit THEIR next transient.

This leads me into that promised bit about how this is possible in small venues.

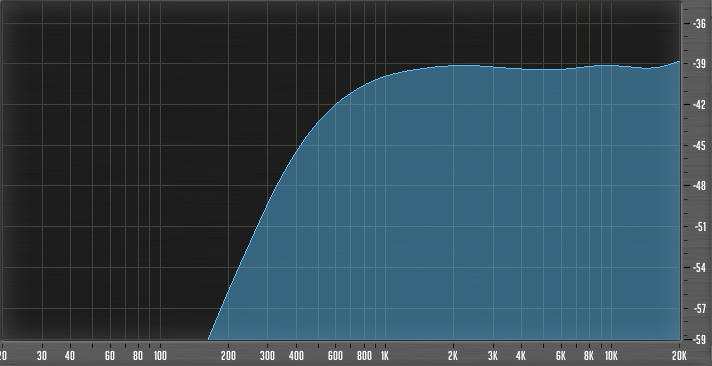

The SPL Difference Is The Key, Not The Absolute SPL Magnitude

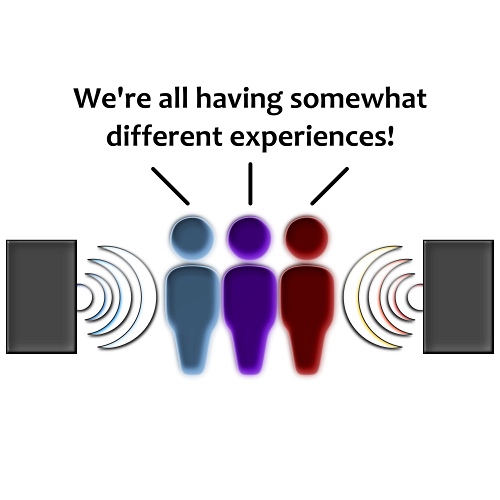

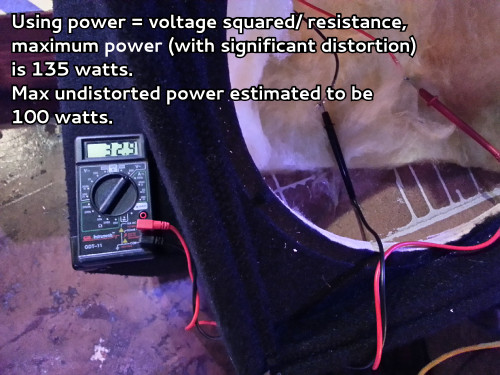

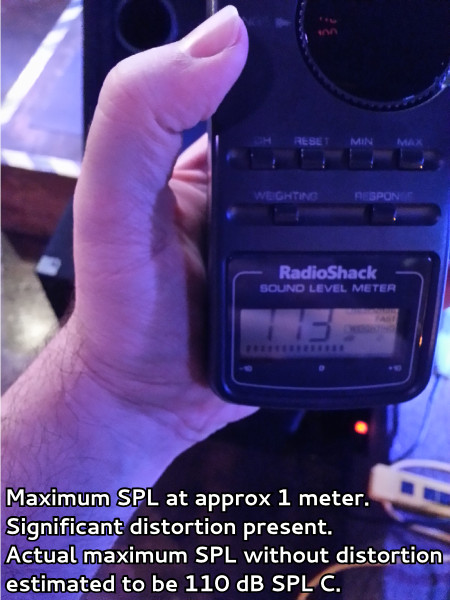

A common mistake in trying to reproduce big-show impact in a small room is trying to replicate the big-show’s absolute SPL (Sound Pressure Level). It’s very easy to think that “so and so sounded huge, and they were making about 115 dBC in the center of the crowd, so that’s what we should do.” What tends to happen, though, is that reaching that kind of level chews up all the power available in a small-venue audio rig. The result is a show that doesn’t have those oh-so-cool transient hits, because there’s just no room for them to assert themselves.

Instead of defeating yourself with excessive volume, what you have to think about is WHY the big-show PA was making 115 dBC in the center of that huge crowd. It’s proportionality. Several thousand humans having a big party can make a surprising amount of noise – and so, to be clearly audible, the audio rig has to make even more noise. If a giant crowd is hollering at 105 dBC, then the audio-human running the system up to 115 dBC is understandable…if maybe a bit excessive. (Or not. It depends.)

From that previous paragraph, you can see that the proportionality between the steady-state volume of the crowd and the steady-state volume of the band was 10 dB. In certain kinds of small venues, that might be a little bit too much. A window of +6 to +9 dB of continuous level above the crowd is worth trying for in most contexts – in my opinion. Note that the “trying” part is most likely going to be in the downward direction. Getting loud is surprisingly easy, but holding your level in check to a point where the crowd is still pretty-darned audible is HARD. It’s hard for bands, and hard for audio-humans, but it’s worth trying for.

The point of holding your continuous level down, beyond just being nice to your crowd, is that it creates space for your show’s transients. Especially if you’re a metal band, and you want that big, thunderous kick, your best chance is to be had by giving the PA lots of room. If the audio-human has to run the system at full tilt just to keep up, then there probably won’t be enough power available to put those chest-thumping transients where you want them to go. On the other hand, keeping the show’s continuous level at a manageable point means that there’s reserve power – reserve power that has to be available to create large, proportional differences for things that need accenting.

Running the audio for Outside Infinity was fun, because they had an instinctive handle on negative space and transient impact. There was plenty of power available for the musical peaks, because the continuous level of the band was appropriate and comfortable. They knew how to articulate their notes so that the music was sharp and defined. I was really impressed.

And, if you take the time to think about your music’s transients, you’ll probably also have a good shot at being that impressive.