A love-letter to patrons of live music.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.Dear Live-Music Patron,

Occasionally, you have a question to ask an audio human. That question isn’t often posed to me personally, although, in aggregate, the query is probably made multiple times in every city on every night. The question isn’t always direct, and it can morph into different forms – some of which are statements:

“I can’t hear anything except the drums.”

“The guitar on the right is hurting my ears.”

“It’s hard to talk to my girlfriend/ boyfriend in here.”

“Can you keep everything the same, but turn the mains down?”

“Can you make it so the mic doesn’t make that screech again?”

And so on.

Whenever the conversation goes this way, there’s a singular question lying at the heart of the matter:

“Does it have to be this loud?”

There are a number of things I want to say to you regarding that question, but the most important bit has to come first. It’s the one thing that I want you to realize above everything else.

You’re asking a question that is 100% legitimate.

You may have asked it in one way or another, only to be brushed off. You may have had an exasperated expression pointed your way. You may have been given a brusque “Yes” in response. You may have encountered shrugging, swearing, eye-rolling, sneering, or any number of other responses that were rude, unhelpful, or downright mean.

But that doesn’t mean that your question is wrong or stupid. You’re right to ask it. It’s one of the minor tragedies in this business that production people and music players talk amongst themselves so much, and yet almost never have a real conversation with you. Another minor tragedy is that us folks who run the shows are usually not in a position to have a nuanced discussion with you when it would actually be helpful.

It’s hard to explain why it’s so loud when it’s so loud that you have to ask if “it has to be this loud.”

So, I want to try to answer your question. I can’t speak to every individual circumstance, but I can talk about some general cases.

Sometimes No

I am convinced that, at some time in their career, every audio tech has made a show unnecessarily loud. I’ve certainly done it.

As “music people,” we get excited about sonic experiences as an end in themselves. We’re known for endlessly chasing after tiny improvements in some miniscule slice of the audible spectrum. We can spend hours debating the best way to make the bass (“kick”) drum sound like a device capable of extinguishing all multicellular life on the planet. The sheer number of words dedicated to the construction of “massive” rock and roll guitar noises is stunning. The amount of equipment and trickery that can be dedicated to, say, getting a bass guitar to sound “just so” might boggle your mind.

It’s entirely possible for us to become so enraptured in making a show – or even just a small portion of a show – sound a certain way that we don’t realize how much level we’re shoveling into the equation. We get the drums cookin’, and then we realize that the guitars are a little low, and then the bass comes up to balance that out, and then the vocals are buried, so we crank up the vocals and WHAT? I CAN’T HEAR YOU!

It does happen. Sometimes it’s accidental, and sometimes it’s deliberate. Some techs just don’t feel like a rock show is a rock show until they “feel” a certain amount of sound pressure level.

In these cases, when the audio human’s mix choices are the overwhelming factor in a show being too loud, the PA really should be pulled back. It doesn’t have to be that loud. The problem and the solution are simple creatures.

But Sometimes Yes

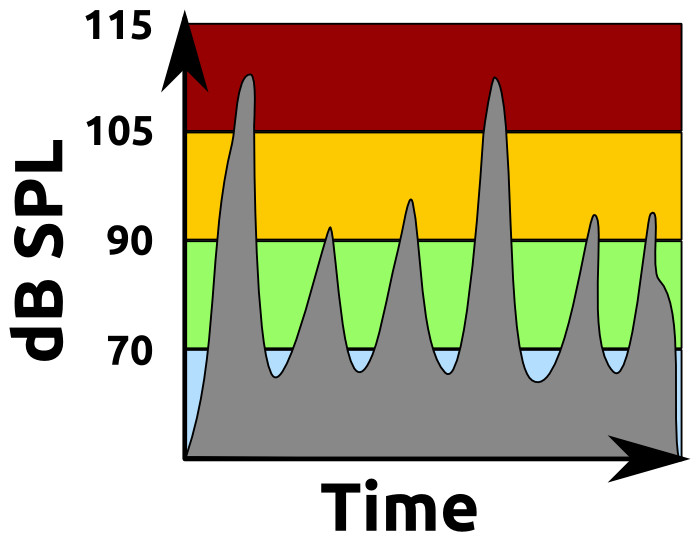

The thing with live audio is that the problems and the solutions are often not so simple as what I just got into. It’s very possible, especially in a small room, for the sound craftsperson’s decisions to NOT be the overwhelming factor in determining the volume of a gig. I – and others like me – have spent lots of time in situations where we’ve had to deal with an unfortunate consequence of the laws of physics:

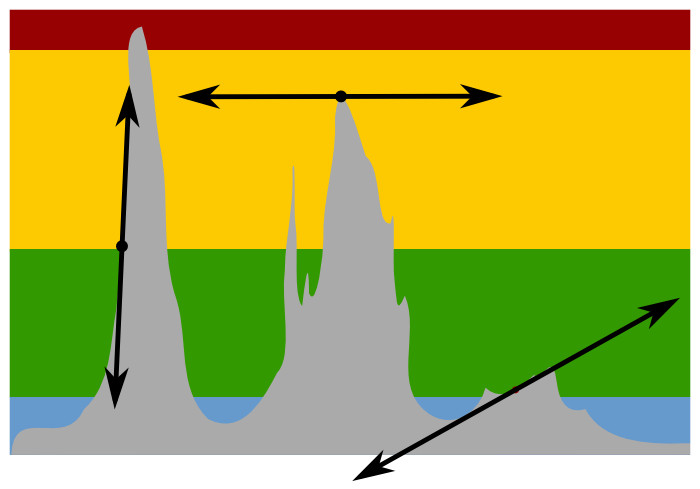

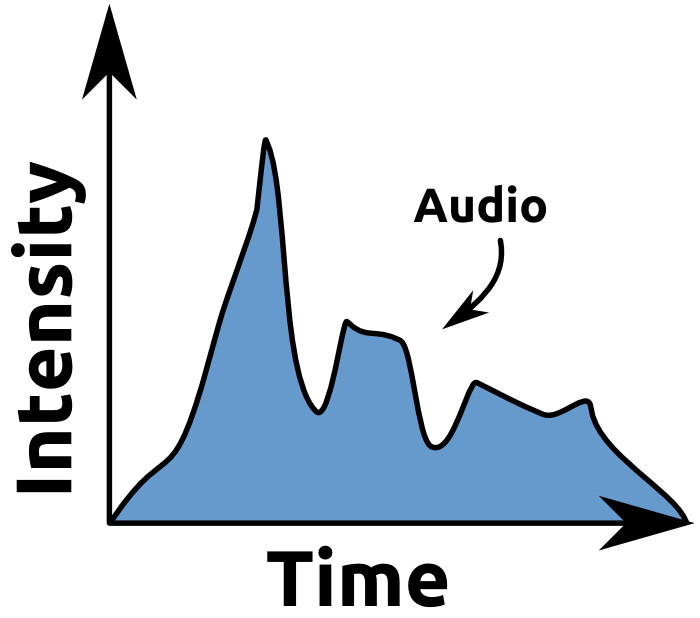

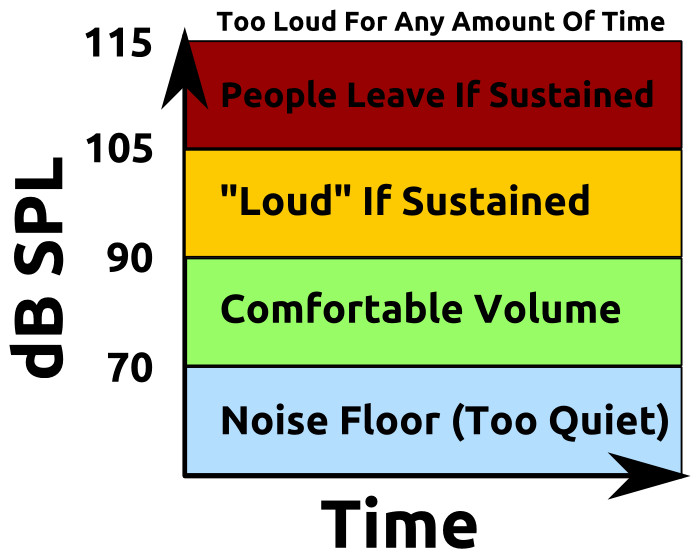

The loudest thing in the room is as quiet as we can possibly be, and quite often, a balanced mix requires something else to be much louder than that thing.

If the instrumentalists (drums, bass, guitars, etc) are blasting away at 110 dB without any help from the sound system, then the vocals will have to be in that same neighborhood in order to compete. It’s a conundrum of either being too loud with a flat-out awful mix, or too loud with a mix that’s basically okay. In a case like that, an audio human just has to get on the gas and wait to go home. Someone’s going to be mad at us, and it might as well not be the folks who are into the music.

There’s another overarching situation, though, and that’s the toughest one to talk about. It’s a difficult subject because it has to do with subjectivity and incompatible expectations. What I’m getting at is when some folks want background music, and the show is not…can not be presented as such.

There ARE bands that specialize in playing “dinner” music. They’re great at performing inoffensive selections that provide a bed for conversation at a comfortable volume. What I hope can be understood is that this is indeed a specialization. It’s a carefully cultivated, specific skill that is not universally pursued by musicians. It’s not universally pursued because it’s not universally applicable.

Throughout human history, a great many musical events, musical instruments, and musical artisans have had a singular purpose: To be noticed, front and center. For thousands of years, humans have used instruments like drums and horns as acoustic “force multipliers” – sonic levers, if you will. We have used them to call to each other over long distances, or send signals in the midst of battle. Fanfares have been sounded at the arrivals of kings. On a parallel track, most musicians that I know do not simply play to be involved in the activity of playing. They play so as to be listened to.

Put all that together, and what you have is a presentation of art that simply is not meant to be talked over. In the cases where it’s meant to coexist with a rambunctious audience, it’s even more meant to not be talked over. From the mindset of the players to the technology in use, the experience is designed specifically to stand out from the background. It can’t be reduced to a low rumble. That isn’t what it is. There’s no reason that it has to be painfully loud, but there are many good reasons why a conversation in close proximity might not be practical.

So.

Does it have to be this loud?

Maybe.