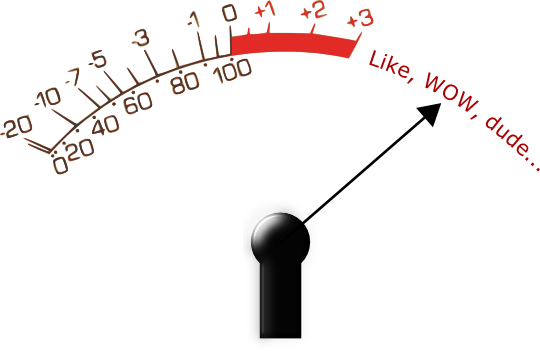

Sound quality is important, but it’s not at the top of the priorities list.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

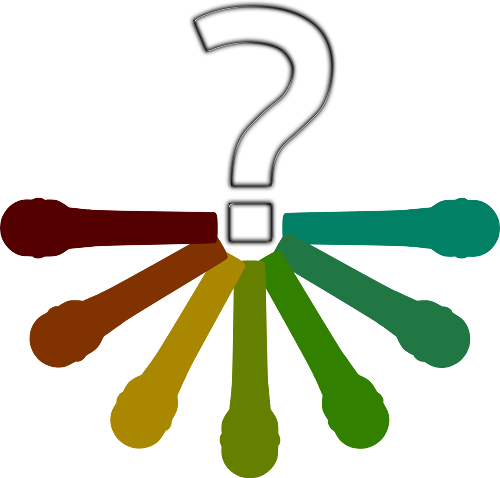

As a live-audio tech, I’m often the guy who supplies all the mics. As such, I end up picking microphones that work for me in a variety of situations. My “favorite pets” are usually the transducers that work without a fuss on 90%+ of whatever they get pointed at. It really isn’t about what’s stunningly stellar for any particular vocalist or instrument rig, because there isn’t time to figure that out directly.

What you might think, then, is that buying a mic for yourself as an individual vocalist would be an exercise in different priorities. At an intuitive level, it makes sense that you would put most of your effort into finding a transducer that sounds amazing when coupled with your voice.

…and of course, you don’t want to pick a mic that makes you sound bad, or is downright painful to listen to.

But…

What’s not intuitive is that you will probably be best-served by satisfying a different list of priorities. That priorities list is basically the same one that a pro-audio human uses – it’s just that you meet it in ways that are specific to you, instead of ways that are generally applicable.

Priority 1: Gain Before Feedback

The most beautiful sounding mic for your voice is completely worthless if you can’t be heard. The most durable mic on Earth isn’t worth a dime if you’re completely and unintentionally buried in the mix. The mic that you could afford “right now” that squeals like a pissed-off toddler and howls like a talkative husky? It just effectively made the spendier mic even more expensive.

The most important thing to look for in a mic for stage-vocals is that it, when coupled with your performance style, can have sufficient gain applied for you to be heard clearly – both onstage and out front.

A complete discussion of everything that effects GBF is beyond the scope of this article. However, there are some rules of thumb that can help you narrow things down a bit:

- You don’t need to worry about the microphone’s sensitivity or overall output. You can think of mic sensitivity as a sort of fixed, pre-preamp gain. It doesn’t necessarily buy you greater feedback rejection. It dictates how much preamp gain is required to get the mic output up to a voltage that’s good for other devices…and that’s it.

- You do need to think about the mic’s polar pattern. Mics with tighter patterns, like supercardioid and hypercardioid models, can be more resistant to feedback when used correctly. The tradeoff with a tighter pattern is that it’s easier to cause feedback by “cupping” the mic, and you have to be much more careful not to move “off axis” during your performance.

- You also need to think about where the mic’s capsule is placed. Certain mics achieve better GBF by putting the capsule very close to the grill – it’s just basic physics. The tradeoff is that you only get the benefit of this placement if you are willing to park your face right on the mic. If you’re not willing to do this, then any benefit of “right up on the grill” capsule placement is lost.

- You don’t necessarily need a mic with “laser flat” frequency response, but you should try to find a mic where the response is “smooth.” Feedback problems are exaggerated by mics with narrow peaks in their response, because the peaks are disproportionately disposed to ringing compared to the frequencies around them. If a mic has a “response peak” or “presence boost” that’s been designed into the capsule, it’s best if the peak or boost covers a wide area – say, two octaves or more.

- Even though a flat response isn’t imperative, you should be wary of mics that are overly “hyped” in one frequency range or another. If a monitor or FOH rig also has proportionately higher gain in the same frequency range, you may experience problems. VERY exaggerated response can cause feedback even if the live-sound rig doesn’t have higher gain in the same range.

Priority 2: Reliability

I chose “reliability” over “durability” because I think there’s more to this factor than just being able to handle wear and tear. A reliable mic stands up to being transported and accidentally dropped, but it also “just works” without being finicky.

The second most important thing to look for in a stage-mic is that it should be resistant to accidents, and require as little external or specialized equipment as possible.

So – what does this mean?

Well, for one thing, it means that condenser mics are less reliable than dynamic mics. It’s not that a condenser mic can’t be made to be quite durable. The drop in reliability comes from the condenser needing phantom power to work. It’s possible to be in a situation where you don’t have phantom available for the mic. It’s also possible to have phantom, and forget to engage it. The mic may be rock-solid, but it becomes effectively less reliable.

(This isn’t to bag on condenser mics, by the way. A condenser may, in fact, be the right mic for you. You just need to be aware of the downsides.)

There are, of course, all kinds of other considerations. If a mic needs a special, odd-sized clip to fit on a stand, it’s effectively less reliable. If its XLR connector has trouble mating with certain mic cables, the microphone is effectively less reliable. If the mic has a switch that’s a little too easy to disengage, the unit is effectively less reliable. If the mic has extremely high or low sensitivity, it’s effectively less reliable.

You might say that another way to express “reliability” is “resistance to unexpected events.” If you can cover the unexpected events by carrying more equipment (a mic pre with phantom power, your own cables, spare mic clips, etc), then you can increase a finicky mic’s reliability.

For the record, the most reliable stage-vocal mics are dynamic units with thick, metal cases, and capsules with sensitivities of roughly -55 dBV/Pa (about 1.7 – 1.8 mV). They require no phantom power, stand up to abuse, and work with the gain ranges available from most preamps.

Priority 3: Great Sound

This might seem like an obvious factor, but it still bears some discussion. You have to think about which mics will sound great on your voice, and in the performance situations that you find yourself in the most. A mic that sounds fantastic when you listen to it in headphones is great – if everybody’s going to be listening to it in headphones. A mic that sounds divine at the venue you only get to play at once a year isn’t a good choice if it’s unflattering through the PA and monitor rigs you play through every other weekend.

Further, a mic has to work well with your performance style. This is similar to the considerations involved with GBF. If the unit is breathtakingly beautiful only when you’re right on it, and you almost never get right on the mic, then you should probably pick something else. On the flipside, if you always have your face planted on the grill, and the mic sounds terribly muddy when you do, then you might want to pick something else.

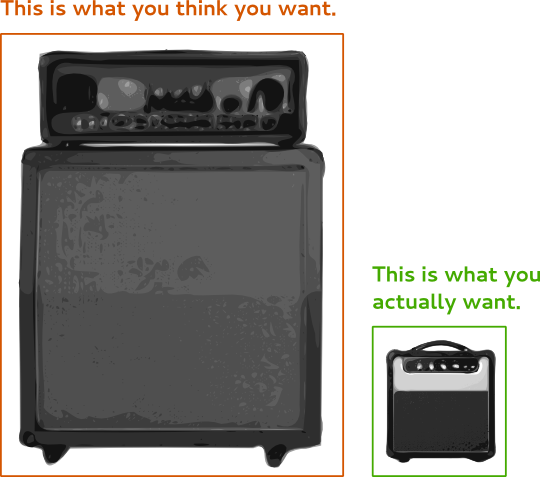

I should definitely point out that you can be VERY surprised by what works well and what doesn’t. Some folks think that the only way to get a great vocal is with a super-spendy mic, but I once heard Katie Ainge sing at a coffee shop with an inexpensive mic connected to a keyboard amp.

It was one of the most beautiful and perfect vocal sounds that I’ve ever heard.

So…How Do You Test For These Priorities?

The actual nuts and bolts of figuring out which mic is right for you look like this:

- Do some research, either empirically or online. If you play at a bunch of different places with different mics, make note of when you could hear yourself, were feedback free, and you liked the overall sound.

- Most mics can’t be returned once purchased, so either borrow or rent the units you’re interested in.

- At rehearsal, try the different mics you’ve gathered up. Feed the signal through a monitor wedge to find out which ones are feedback resistant while sounding as nice as possible.

Recommendations

To help narrow down the bewildering array of choices to be had in the vocal mic arena, here are a few transducers that I’ve had decent experiences with:

Shure SM-58 – I’m really not a fan of the 58, but that doesn’t make it an invalid choice. Most 58s that I’ve run across have ended up sounding muddy, with a rolled-off top end, but there are some voices that they’re just perfect for. The SM-58 has a cardioid pattern, workable GBF, and is capable of surviving a LOT of punishment. SM-58s seem to be slightly more forgiving of shaky mic technique than some other products.

Shure Beta 87a – These are mics that Stonefed carries with them for road shows. I would characterize them as “pretty okay.” In certain situations, we had some issues with feedback at very high frequencies (in the range of 15kHz). Their clarity can border on “whininess” in some situations, and they have more mud than I think a condenser ought to have. I’d probably cut these mics more slack if they weren’t $250 a pop – to me, that’s a lot of money for something that isn’t my favorite. The “a” units are supercardioid, so you need to stay on axis and avoid cupping the grill.

Sennheiser e835 – Bought singly, an 835 costs about as much as an SM-58…but I’ll take an 835 over an 85 any day of the week. These mics seem to have far less of the “Shure-standard mud,” coupled with a crisp top end. That same crispiness may be a bit much, depending on your tastes. GBF on these mics has rarely been a problem for me, but every so often I’ve had some trouble with ringing at low frequencies. An 835 is a cardioid device.

Sennheiser e822s – A major advantage of the e822 is that you can still find it in packages for about $50 a unit. These mics are surprisingly good for the price. I personally own a handful of them, and they have been just as reliable as more expensive units. I personally prefer the sound of these mics over that of an SM-58, but they do still have a bit of mud and garble to manage. The GBF on an 822 seems to be comparable to other mics I’ve used – sometimes even a bit better. Sennheiser e822 units are cardioid.

Audix OM5 – These mics are VERY crisp. So crisp, in fact, that you can really tear people’s heads off if things get loud. On the other hand, I’ve heard these mics deliver live vocals that sounded like a world-class studio recording. Their GBF is definitely “pro-grade,” although their marketing might make you expect miracles that they can’t deliver. OM5s are hypercardioid, so they’re best for people who aren’t shy about sticking their face to the mic.

Electrovoice N/D767a – The 767a is one of the few mics I’ve heard that seems to get the top end exactly right. They have nice clarity without being overhyped. The bottom end of the frequency response is okay, but these mics do seem to suffer from breath noise and plosives more than some others. They don’t display as much muddiness as other mics, but some situations will still require a good bit of EQ. The GBF on these supercardioid mics seems to be on par with other, professional level units.