Everything tried to kill Fats, but tenacious ownership kept it alive.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.Everybody hated the giant patch of nothing that was next door to Fats. A testament to the economic catastrophe of 2008, the “Sugarhole” was a titanic wound in the middle of Sugarhouse. Buildings had been torn down in advance of a giant “renewal” project that had ground to a tooth-scraping halt. When the project finally got back underway, there were smiles all around. If the old Sugarhouse had to be no more, it should at least be no more with a new, shiny development in place. Something to look at, you know.

As the new building went up, Mario started running numbers in his head. The grand, rejuvenated Sugarhouse center would be a mixed-use affair, with condos sitting atop commercial space. Mario figured out that just 2% of the occupants, visiting twice a month, would change Fats forever.

We would have to live through the construction project first, though.

As the build got into full swing, the problems began. Small disruptions have enormous effects upon small businesses. You might not think that a minor inconvenience to vehicle traffic would be a big deal, but it’s a near-lethal poison to the local shop. As the area around Highland Drive got more difficult to traverse, the consequences were definitely non-trivial. As formerly reliable parking was chewed up by contractor personnel, people found other places to be.

Daytime sales dried up.

Mishell went to war.

Fats and everybody in it were basically Mishell’s other baby. Messing with somebody’s kid is a surefire way to get into a no-holds-barred battle, and somebody was messing with Mishell’s kid. Month after exhausting month, she did battle with accounts, landlords, slipping sales, Utah’s bizarre liquor regulations, equipment failures, and plumbing problems, all while keeping on top of booking shows. She found an advocate with the city to try to bring Fats through the construction problems. It was revealed to us that, adjacent to projects like the one taking place a few hundred feet north, 80% of local businesses bail out or just flatly fail. Mishell was determined, come hell or high-water, that we would be in the 20% column.

As the project reached its completion, we all started to breathe a sigh of relief. Maybe we had made it. Maybe we were about to see the revitalization that comes from a bunch of new, urban-minded people being on the block.

The sigh of relief was interrupted as though all the air in the city had been blown away into space. As the new eateries and brew-pubs opened, our lot was again jammed to the gills…with people going other places. The promised revitalization WAS happening, but not for Fats and the other longtime tenants. If you were inside the footprint of the new development, business was booming. If you were outside that footprint and merely in the shadow of that “leading-edge,” high-density monstrosity, you were invisible.

And yet, we were NOT out of business. Our people still came in when they could. The shows continued without interruption.

Oh, and when the shifts were over at those “johnny-come-lately” places? When their workers were done and needed to unwind? I’ll give you one guess as to where they went for a beer and some tasty eatings. That’s right.

Fats was covered with battle scars. Fats was struggling. Troubles and challenges loomed over that brick-walled, Sugarhouse shoebox like a thunderstorm ready to drop a torrent. Fats, though, was still standing, and Mishell simply refused to quit.

There was a point where Fats changed how bands were paid. We started out on the guarantee model, where a band is compensated with a set amount of money for appearing. It’s a simple, well-liked setup that keeps things easy, but it’s also financially challenging. For a bar to pay a guarantee, that guarantee has to basically be surplus. It means that a predictable amount of business will be done by the bar on any given night, and that the band is meant to be a sort of “garnish” on that revenue stream. The party is already going to be in the room; The band will make the party last longer.

If the bar’s business is UN-predictable, however, running a guarantee system becomes a huge liability. If the public only shows up for the bands they specifically want to see and hear, you can only pay guarantees to bands that establish a track-record of drawing a crowd. For everybody else, you have to pay a percentage. If you don’t, the venue runs its cash reserves into the toilet, and the doors close.

Mishell was not about to shut down the basement venue, so we moved to a percentage system.

Some people were very upset, and I can understand why. Whenever we feel like something is being taken away, we humans tend to take it badly. There were folks who simply couldn’t afford to play Fats gigs anymore, and we understood. If a band needs to play “guarantee” gigs as part of its business model, that’s just the way it is. There was nobody at Fats who couldn’t respect that.

What got me pretty “hot,” though, was when a few folks wanted to paint Mario and Mishell as being “disrespectful” to musicians by instituting the percentage system. There was zero disrespect involved, I assure you.

To start with, real disrespect of musicians is promising one thing and then delivering another. At no point was anyone intentionally promised guaranteed pay, and then (also intentionally) switched to a percentage when things weren’t working out at the bar. A small minority of gigs were still done on the basis of a guarantee, and there were a few issues of misunderstanding or miscommunication, yes, but there was no “intention” involved. I was never, EVER told to short a band so that Fats would make a few more bucks. Mishell had far too much respect for players to do something like that. Also, the transition to the percentage system was done slowly, and with quite a bit of open discussion. There was no bait-n-switch involved.

Real disrespect of musicians is asking someone to play for free. Mishell never asked anyone to play for free, that I was ever aware of. Someone might argue that percentage pay can result in playing for free (or so little as to be effectively playing for free), but that’s not disrespect. What that ACTUALLY comes down to is simple misfortune. Disrespect is making a bad promise, and then expecting people to like it.

Let me dig into that a bit.

Band pay at a bar has a left side, and a right side. The left side is the bar’s revenue, and the right side is the multiplier on that revenue for band pay. When musicians are being hugely disrespected, the right side multiplier is dropped to zero. This is commonly expressed as “the gig will be great exposure!” It looks like this:

Bar Revenue (maybe big, maybe little, who knows) X 0 (Exposure! Experience! Good vibes!) = 0.

In the case of the entirely respectful, pre-arranged percentage, the multiplier is held constant. Nobody is being asked to play for free. They’re being asked to accept that there’s a risk that the math won’t result in a big pile of money. They’re being asked to be in the same boat as the club. Here’s how the math looks:

Bar Revenue X Fixed Percentage That Was Agreed Upon = Some number, which is never intended to be zero (but could be, if things go very badly).

Mishell had far too much respect for musicians to float the idea that the right-side multiplier should be zero.

Beyond that…

We had so much respect for musicians that we left the stage-extensions up, even when Floyd Show wasn’t playing, so that everybody could have more space.

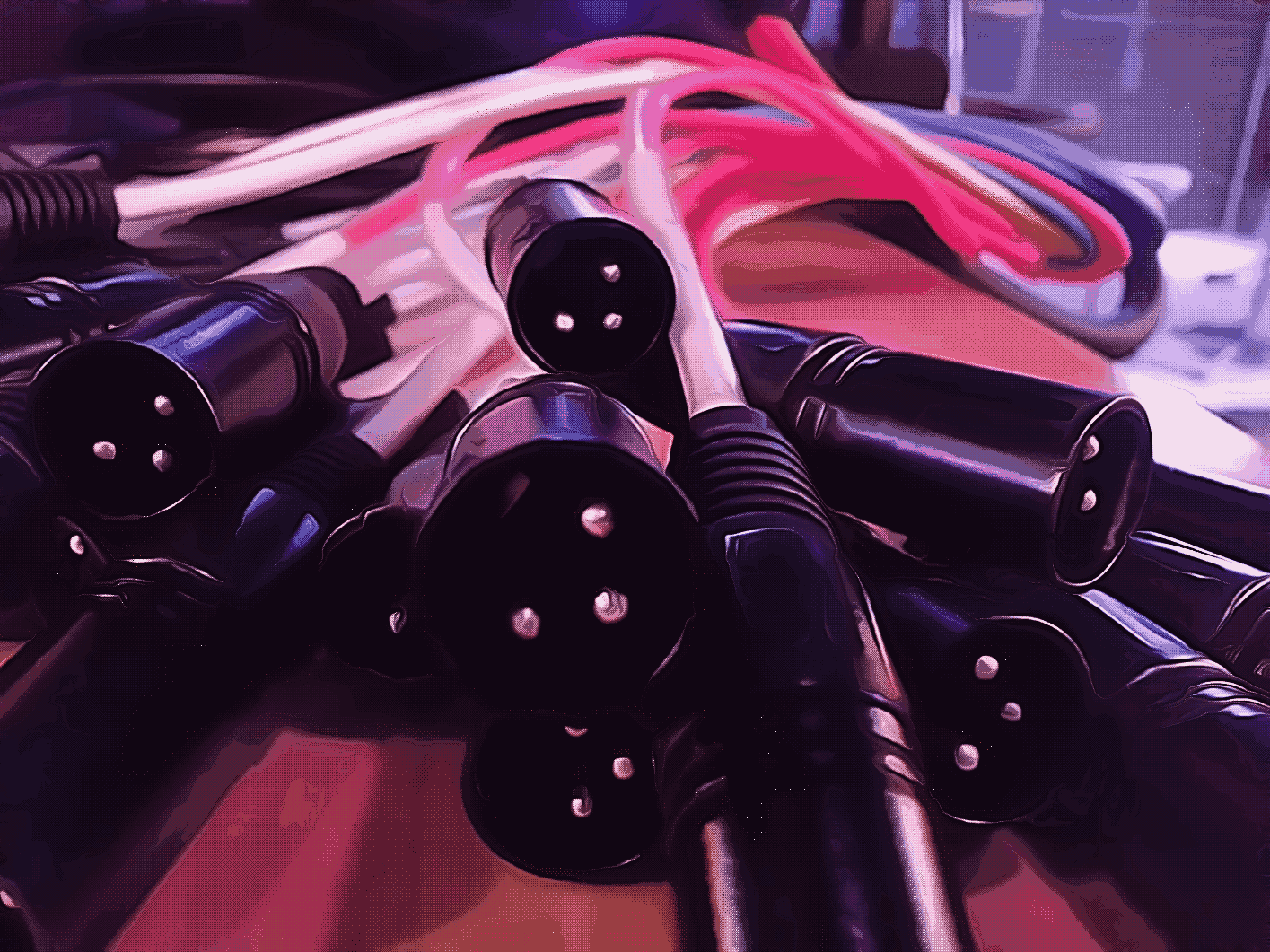

Mario and Mishell had so much respect for musicians that they effectively backed me on my hair-brained scheme to build a computerized mixing console – a console that let us do all kinds of cool things, like multitrack shows with a button-push, and beat difficult monitor situations into something that resembled submission.

Mario and Mishell had so much respect for musicians that they remodeled the basement into a “small but mighty” venue, a venue which elicited praise from players with decades of experience in tons of different rooms.

Mario and Mishell had so much respect for musicians that they paid me more than they could easily afford (for years and years), so that bands playing at their venue would be guaranteed a tech who actually cared about what was going on.

We had so much respect for the musicians that we kept adding more and more production to the venue. In the end, we had a tastefully designed (if I do say so myself) light show with movers and haze, along with an eight-mix monitor rig on deck. We wanted the shows to be as much fun as they could possibly be.

Mishell had so much respect for musicians that she continued to pay for print-ads about live music at Fats.

Mishell had so much respect for musicians that, in the face of all the troubles and struggles that beset Fats, the basement stayed open, weekend after weekend, all the way to the end.

Musicians might not have gotten rich from playing at Fats, but they were always respected there.