Every once in a while, I get a request for information on how to create or add-on to a system for live audio. I like to personalize this information, because rigs for show and event production are best built for specific applications. However, there is a point where insisting that everything be approached in a customized way becomes inefficient – a lot of the same ground gets covered repeatedly.

So…

If you’re wondering what I think is required for a “small, basic, but still worthwhile” audio rig, read on. I’ll be including lots of links to vendor pages where you can buy various products.

(We’re going to go in order of signal flow, by the way.)

Input Transducers and Interfaces

For the smallest possible rig, take a distributed approach: With anything other than vocals, have the musician supply their own, personalized sound. Further, seek to avoid the whole issue of putting the output of that sound through the PA. Let a guitar amp make the guitar sound, let the drums just make their own noise in the room, and so on.

Having the ability to put more in the PA increases your potential control over the sound of the show, but outside factors can prevent that potential control from becoming actual control. Also, more inputs means more complexity, and thus more difficulty in system operation. There’s no hard and fast rule of what to be ready to reinforce, but I generally encourage folks – especially folks new to this whole thing – to ease themselves into the maelstrom that is live audio.

Wired Microphones

A decent mic will basically sound like the thing it’s being pointed at. For this reason, don’t agonize about getting specialized mics for everything right off the bat. A good “vocal” mic will be fine for many, many instrument applications. I recommend buying mics with tighter patterns (super or hypercardioid), as they can make the handling of high-gain situations much easier. Tight-pattern mics do require that the musicians – especially the vocalists – be able to use them appropriately. This issue should be considered as something for the musicians to figure out, because no system can fix everything (and a basic rig can fix even less of everything, if you take my meaning).

My current favorite mic is the EV ND767a. You might also consider the Audix OM2. Here’s a comparison of the two at Sweetwater.

Microphone Accessories

Each mic you buy will require an appropriate stand and XLR-Female to XLR-male cable.

Budget stands (like these from OnStage Stands) are just fine… if you can put in the effort to be nice to them. Gator Frameworks also has some promising offerings.

When it comes to cable, don’t overspend and don’t oversave. For a 20+ foot mic cable, paying more than $1.00 per foot is a huge premium for no benefit that I’ve been able to clearly observe. There are perfectly decent cables that can be had for as low as $0.40 per foot when purchased in a bundle. Going much below that, though, is likely to lead to problems.

I’ve been quite happy with cables I’ve gotten from Audiopile and Orange County Speaker. I’ve gotten some REALLY inexpensive cables from Unique Squared that were okay for a good while, but started having problems after a number of uses.

Wireless Mics

One word: Don’t.

Wireless is a pain in the donkey, with the FCC selling off all kinds of UHF spectrum to cellphone and computing companies, and the frequencies used for digital wireless becoming ever more crowded and hostile. Functionally, wireless transmission of audio is far more “fragile” than signal running on a cable, with all kinds of weird things that can happen outside your control.

But no matter what I say, you’re going to buy at least one wireless mic anyway, so…

Buy a digital system that operates in the 2.4 Ghz band if you want a chance at retaining your sanity in the short term. Specifically, look at the XD-V55 systems by Line 6. They’re very reasonably priced, have nice features like remote monitoring of mute status and battery level, and are the best wireless experience I’ve personally had to date.

You can, of course, go up from there.

Wireless Mic Accessories

Handheld wireless mics benefit greatly from having a stand available for every transmitter. Further, each receiver will need a cable to interface with the rest of the system.

Direct Boxes

A direct box is what I class as an “interface,” because it doesn’t convert acoustical events into electrical signals. A DI makes signals that are already electrical play nicely with pro-audio equipment when they might not otherwise. An aspect of this is also isolation, in that the DI creates what you might call an indirect connection between a console and a device. This can be very handy if the sending device (a guitar, keyboard, sampler, whatever) can’t tolerate phantom power, and the console has phantom applied to the signal line in question.

Direct boxes come in two main flavors, passive and active. Active DI boxes require external power of some kind, be that power from the wall, batteries, or phantom from the console. If you’re going to buy DI boxes, buy ACTIVE models. An active DI will work with almost anything, whereas some instrument pickups pair quite badly with passive boxes. You might as well buy units that work everywhere, and thus simplify your life. Expensive models from BSS, Radial, and Countryman are certainly nice, but there’s great value to be had in units from ART and Behringer, especially the “multiple modules in one box” offerings.

DI Box Accessories

Just like a microphone, each DI box will require an XLR-Female to XLR-Male cable. Remember that multi-module DI boxes require a cable for each individual module.

You don’t have to actually mount a rackable DI system, but you might want to. Sweetwater and Audiopile both sell quality rack cases in a huge variety of configurations.

Snakes/ Multicore Connections

Depending upon how you implement the mix and signal processing part of the rig, you may or may not require multicore cabling. If you want to send and receive a bunch of audio signals at a remote location, a snake really is a must. If you merely want to control the processing of signals from a remote location, you might be able to use your console in the same way you would use a traditional snakehead or stagebox.

If you do use a multicore, I suggest getting one that’s a little “overkill” in terms of the number of lines it contains. If a line fails, you’ll have a spare to patch to. “Headless or “fan-to-fan” snakes are a bit cheaper, but less convenient than multicores that terminate one end at a box. (You will always have to hunt for the specific line you want to connect to. It’s like a law of nature, or something.)

Audiopile would be my first choice for buying a snake I was really serious about. I have had good results with Seismic Audio fantail-to-fantail snakes, but my experience with their stagebox offerings has been mixed.

Mixing Consoles and Output Processing

This is where things get REALLY interesting.

Essentially, you have three major choices:

1) Use a relatively simple console where output processing is handled externally, and place all that at a “remote” location.

2) Use a more sophisticated console that encapsulates the output processing, and place the console at a “remote” location.

3) Use a more sophisticated console that encapsulates the output processing, leave the console close to the stage, and control the console from a remote location.

Option one takes up more space and requires more complicated physical patching, but the interface can be easier to understand at an intuitive level. Option two is compact and easy to physically patch, but the whole thing can be less intuitive for an inexperienced operator. Option three is like option two, with the added issue that control can depend entirely on an external device and network connection. If those fail, you may be in big trouble.

In every case, a console with some room to grow in terms of both inputs and outputs is a good idea. Don’t go overboard, though. You’ll end up spending a lot of money to no functional end. Especially if you’re new to all this, keep your monitor sends down to a maximum of four.

Option 1

The Console

Whatever you do, buy a console where the EQ has sweepable mids on the EQ and pre-fader auxiliary sends for each unique monitor mix you want to handle. A Soundcraft EPM8 is probably the minimum you should look for. I’ve been quite pleased with Yamaha’s mid-basic offerings, which have been revamped since I’ve bought one.

Simple, analog consoles “race” in a VERY tight pack, which means that there are lots of little permutations and many viable choices. Mackie, A&H, and Peavey are all worth looking at, and Behringer, while not having the shiniest reputation, has a knack for cramming lots of features into small cost. An XL2400 has what I would consider to be pretty darn flexible routing for a $650 mixer.

Console Accessories

Some consoles can be easily cased up or rackmounted, and some can’t.

You will need patch cables and/ or adapters with appropriate ends to get from your console outputs to your processing, one cable for each channel. As with other cables, high-dollar options really aren’t necessary. Stay somewhere in the $2/ foot range, and you’ll have patch connections that are long enough for some wiggle room and cheap enough that you won’t cry about ’em.

Also, get yourself a decent set of headphones for listening to the console’s solo bus. I have a pair of very-well-loved HD280s, and lots of other options exist. You want to look for closed-back, durable, “un-hyped” phones if you’re doing your own hunting.

The Processing

What you choose for output processing depends greatly on your own personal taste and comfort level. At the minimum, you should have an independent EQ for each mix. A really basic setup might be three mixes – one for the audience, and two monitor mixes for the stage. Things go up from there, of course.

Graphic equalizers, while not my personal favorite, are straightforward for most folks to operate. I generally recommend 31-band models over 15-band units, because you can focus in on a problem area without sledgehammering material that’s not making trouble. Peavey and dBX are good overall bets, but affordable graphics are similar to affordable consoles: All the players are very similar. I do like the features of the Behringer FBQ3102, but I also had one die after a year of use and a bumpy ride in the back of a truck.

If I’m going for an EQ-only solution, I can tell you that I vastly prefer a flexible parametric EQ over a graphic. In that realm, I have been extremely impressed by Behringer’s Feedback Destroyers. To be clear, my experience is that their automated feedback management is mediocre at best – but they are WICKED HANDY when you run them manually. You get a huge number of fully parametric filters at a very low price point. I’ve never had a major problem with any Feedback Destroyer I’ve owned. (Be aware that parametric EQ is more involved than graphic EQ. It’s not quite as “grab-n-go.” There are more choices that you have to make deliberately.)

If you want your processing to include dynamics, and also to let you have a graphic EQ combined with a parametric EQ, then a Behringer DEQ2496 is another killer device. Again, I haven’t found anything else exactly like it “in the wild,” although a Driverack PA2 is actually very close. DEQ2496 units do sometimes have problems with one of the internal connectors getting loose, but it’s an easy fix once you get the cover pulled off the device…and the connector freed from being glued down. (You will very definitely void your warranty if it’s still in effect, but hey, live a little.)

Processing Accessories

You may or may not be able to patch your snake returns (or other output cables) directly to your processing, so some adapters or patch cables might be necessary.

Also, you should definitely rack up any outboard processors you have for your system. It really does help to keep things neat and tidy.

Option 2

The Console

Digital consoles are a great route to take if you want to keep everything in one box. The downside, of course, is that the one box becomes a single point of failure. Then again, in any case, losing the console pretty much ends your day if you don’t have a spare.

Another factor to consider is that the processing available in digital consoles tends to be more fully featured while also being somewhat abstracted. This can make them overwhelming for new users, who simply don’t know what to make of all the options available.

If you’re going to be physically present at the console, you may as well get one that has a control-surface integrated in some way. An X32 Producer is a pretty natural choice, along with offerings from Presonus, Allen & Heath, and QSC.

Console Accessories

As was said earlier, rackmounting or casing the console might be possible. You can decide if you want to go to the expense or not.

The need to buy patch cables or adapters may still be there, depending on the configuration of your snake or other output lines.

And you’ll still want some headphones.

Option 3

The Console

You can leave the console on stage and mix remotely with the consoles detailed above, although the control surface might be a bit of a waste. Affordable digi-mixers that lack a surface are an interesting new product on the scene – just remember to factor in the cost of a remote-control laptop or tablet. Also, be aware that remote control is inherently a bit more “shaky” than being physically present at the mixer. It’s not horribly problematic, of course, but you have to have a contingency plan.

Surfaceless consoles at lower price points are available from Behringer, Soundcraft, and A&H. More expensive units also exist, of course.

Console Accessories

Surfaceless consoles are definitely rackable, and definitely should be.

Remember to buy the necessary patch cables or adapters for the outputs.

…but you can probably skip the headphones, because the consoles don’t currently stream the solo bus to a remote location (that I know of). That’s another downside of the number three option – to access the solo bus, you still have to be physically present at the console’s location.

Output Transducers (Speakers, That Is)

You’ll notice that I didn’t include an option for amps and passive speakers, and there’s a reason for that: This is supposed to be a simple system, and powered speakers are really the way to go to achieve simple.

Also in the service of simple is to keep your monitor wedges and FOH speakers interchangeable. Unless it’s completely inappropriate for your application, having loudspeakers that are all of the same model means that you can expect similar behavior from each box. If a failure occurs, you can swap one box for another and not have to think about it too much.

When buying powered loudspeakers, accept nothing less than an honest-to-goodness, biamped, fully processed unit. There are plenty of powered speakers that are single amped, with no processing outside of a passive crossover that is placed between the amplifier and the drivers. You want something more – something with an active crossover, basic corrective EQ applied at the factory, and an internal limiter. A peak SPL rating of greater than 120 dB @ 1 meter is also a good thing to look for, even with all the “fudging” that marketing departments apply to output numbers.

In terms of specific recommendations, I can say that PVXP12s have done very well for me. I can do “rock and roll” monitors with them in a small space, and I’m confident that they would perform equally well as an FOH unit. There are lots of other possibilities of course, provided by JBL, Mackie, Yamaha, and Behringer (just to name a few).

Loudspeaker Add-Ons

First, make sure you have the necessary cables to get from the console or snake outputs to the loudspeakers. Because speakers tend to be deployed in a rather spread-out fashion, it’s advisable to buy a bit more cable than you think you need. A 50 footer for each loudspeaker is probably a good start.

When it comes to stands for your FOH speakers, it’s good to get something a little nicer. Stands with locking collars and/ or piston assists can be a big help. I’ve used crank stands in the past, and they’re okay, but given a chance I’d make the upgrade to a more technologically advanced support.

The Biggest Accessories Of All

In the end, none of the fancy gear will mean much without power. You don’t have to buy really fancy power-conditioning equipment, but some rackmountable power units help reduce the need to fish around for a bunch of “free range” power taps. Of course, you should still keep a few freely-positionable power taps handy, along with several extension cords that use 14-gauge conductors (or something beefier, like 12-gauge). Powered speakers spread out all over creation have an alarming tendency to need those extension cords.

While there are other sundries and gadgets you can add on, going through the above should get you a working rig. As I said, this is a basic system. It won’t do everything for everybody all the time, but it should provide you with a decent start.

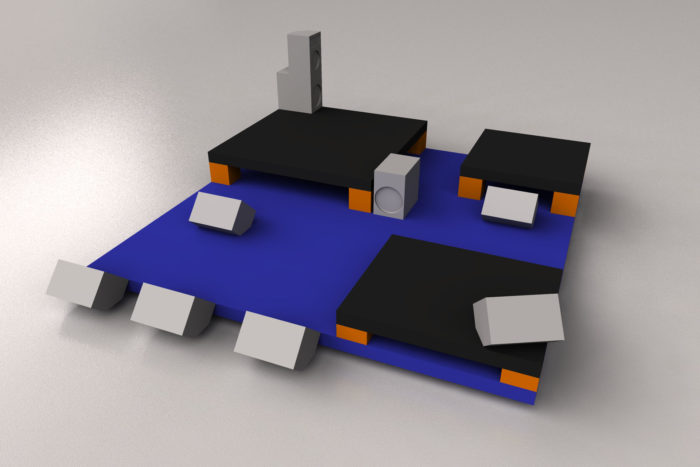

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

![[micinfographic]](http://smallvenuesurvivalist.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/micinfographic-700x417.jpg)

![[myface]](http://smallvenuesurvivalist.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/myface.jpg)