Life is different when small changes are very audible.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

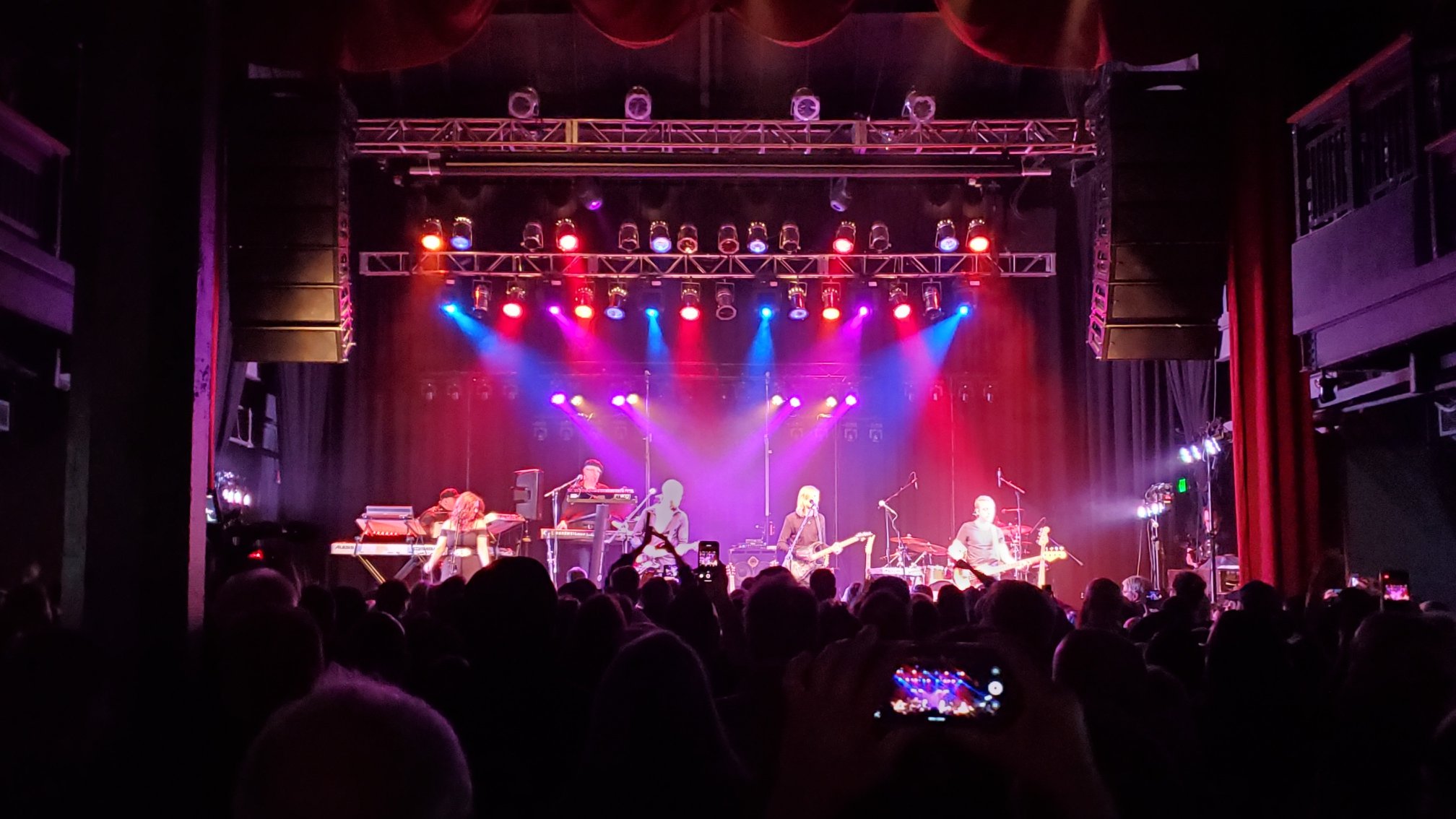

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.I’m very proud to work with a Pink Floyd tribute called “The Great Gig.” We recently had a show at The Depot, one of the premier music venues in Salt Lake. Mixing in that room is very different from mixing in other rooms, and not just because it’s a rather large-ish place by my standards.

And also not just because they have a big PA with lots and LOTS of reserve power. Although that is a HOOT, let-me-tell-ya!

It’s because mixing there is what I call a “low-inertia” process.

In smaller spaces, you have the opposite. They’re high-inertia, because of the very large contribution of acoustic energy that’s essentially independent of the PA system. Any changes you make to the mix in the FOH PA are dampened: You get on the gas with a guitar to the tune of +3 dB, and unless you’re already much louder in the PA you don’t hear a huge difference. You yank the snare drum all the way out, and the snare doesn’t disappear because it’s already quite loud in the room. You might just get a bit of a tonal change, with the overall blend seeming to be quite similar.

In The Depot, though, a pretty tame room and reasonably absorptive stage mean that it’s possible to really, REALLY hear the PA over the stage wash without being insanely loud. That means low-inertia. You give a guitar a small push, and you hear that small push. Yank certain things down and they get much more lost than they would otherwise.

It’s a cool thing! Your faders, EQ, compression…all your processing tools are much more responsive. It’s also challenging, though, because the mix in the room is very strongly about your choices with fewer safety nets. There’s much less filling in the gaps. If you don’t get something tweaked quite right, it’s very audible. A little bit of buildup in the main mix that hasn’t addressed with the bus EQ? It can bite you in the face.

But, at the same time, you don’t have to sledgehammer with that main EQ. You can be much more subtle…and you can also do some tantalizingly wild things due to your relative independence from the stage. I imagine it’s rather similar to driving a car with a very light body and a very big engine. Small control inputs have large consequences.

It’s definitely enjoyable to mix in a low-inertia situation, but it takes a bit to get used to. You can also get yourself into trouble quickly. You have to be willing to own your choices, and be honest with yourself if you’re not pleased with the way thing are going.