The (not so secret) sauce behind audio production for Pigs Over The Depot.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

For weeks now, I’ve been meaning to open up the show files from Pigs Over The Depot (A Tribute To Pink Floyd) and go through some parts therein. I finally got off my rear and got busy! Here are some selected thoughts:

Routing

The show routing was really straightforward, with one small twist in monitor world:

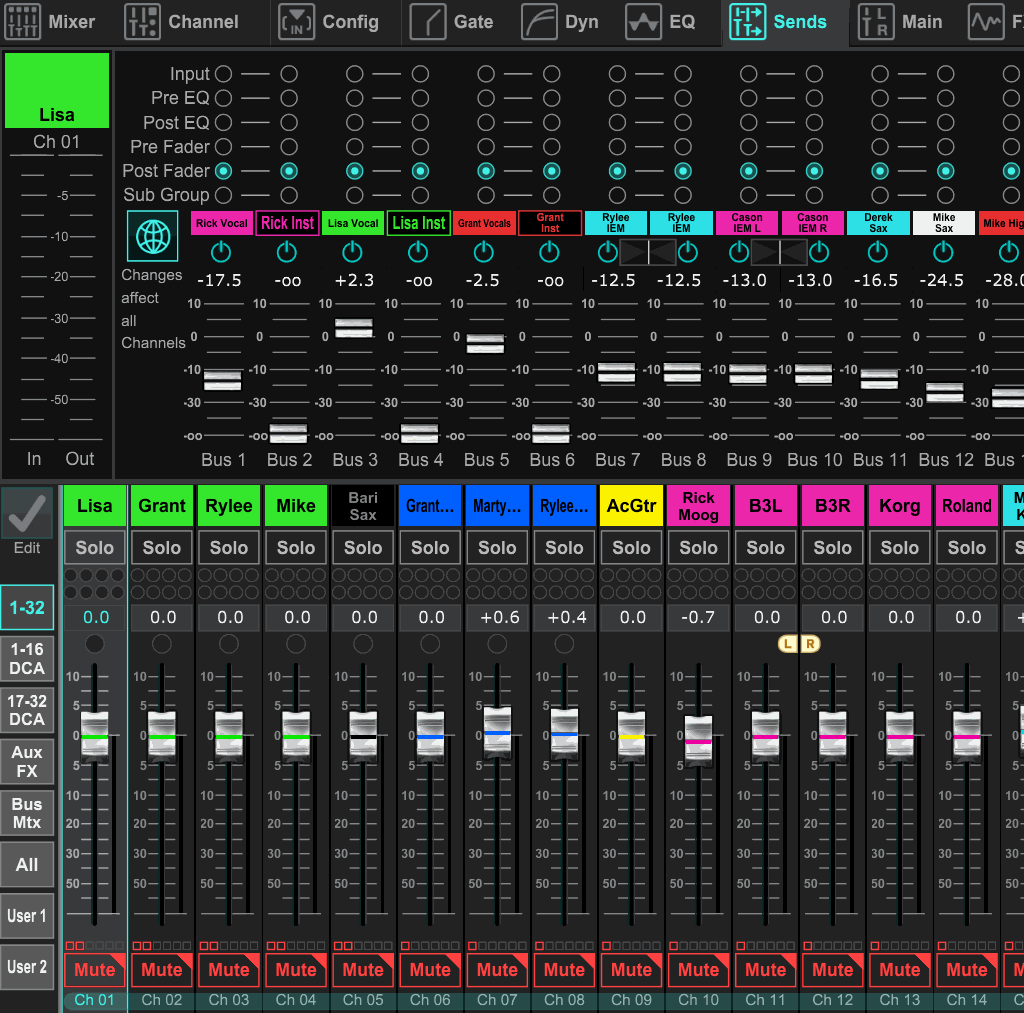

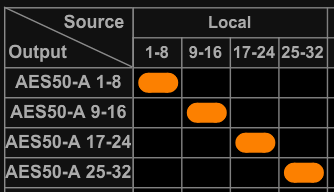

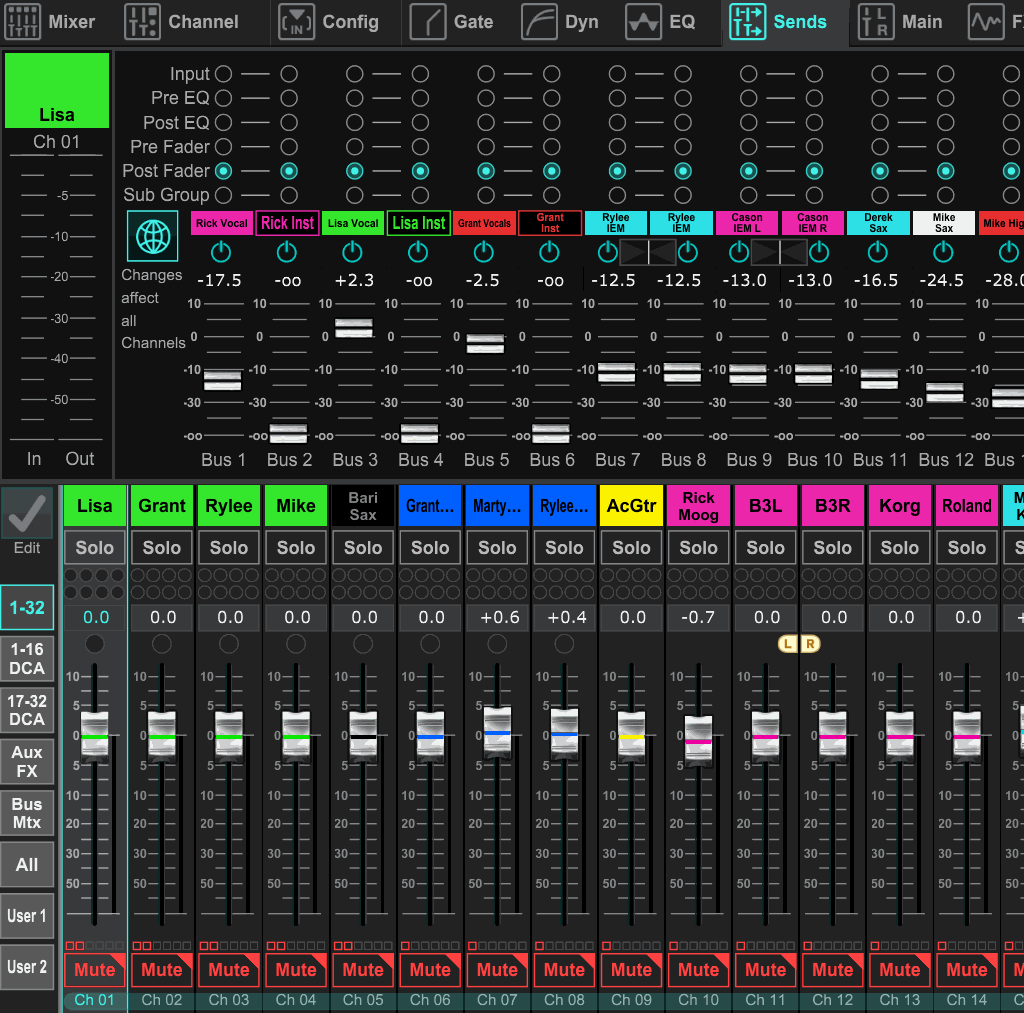

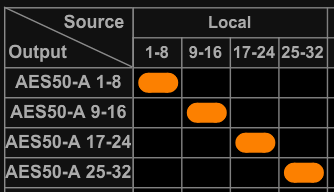

The monitor console was gain-master for the show, because all analog input was handled by it. FOH was an X32 core connected by AES50, meaning that four of monitor world’s AES50A Output routing blocks needed to be sourced from the local inputs.

Some folks might look askance at such a setup, but it’s just fine for me. Jason, the monitor engineer, is a top-shelf operator. Plus, neither of us are preamp twiddlers. Jason figured out a good, healthy input level for his headamps, and left them alone after that.

FOH was connected to its own AES50 stagebox for physical tie lines to The Depot’s system. Driveback through monitor world’s auxiliary channels would have been possible, but easy, XLR connectivity was my priority for the evening.

Buses and VCAs and FX, Oh My!

FOH

On my side, I had two mix buses going on: Vocals and Drums. I wanted to be able to EQ and compress all the vocal and drum mics as separate groups, especially if there was a consistent “vocal garble” frequency giving me trouble. I also wanted to have a quick control for “more vocals NOW,” if the need arose.

As is my usual, I had a main L/R mix and a separate send for subwoofer material.

For FX, I set myself up with three options: Hall Reverb, Long Delay, and Regular Delay.

The reverb was driven hard for “Great Gig In The Sky,” and Grant had a guitar part that needed to be fed through it. Other than that, I tried to be pretty sparing.

The long delay was specifically for the echoing “Stone!” in “Dogs,” with the left-side of the delay having a time of 1.5 seconds and the right side being set for one second. I used quite a bit of feedback in order to make the echoes last longer, but I still feel that I undershot a little on my settings there.

The regular delay was 0.5 seconds with only a touch of feedback, and I didn’t lean on it very much. Mostly, it ended up being a vocal texturizer on “Great Gig In The Sky.”

Due to a late-breaking addition of a second channel for the Juno synth which got pushed off into a spare line that would have been for drums, I couldn’t stereo link the Juno inputs. I should have just bused them together, but I went for a DCA instead. Clever – but I didn’t realize that the DCA was muted until we were a few songs into the first set. Whoops!

Monitor World

In monitor land, there was a true extravaganza of feeds for Jason to mix. The first six buses were monitor wedges deployed in pairs but fed with total independence. One wedge was dedicated to carrying a vocal mix only, while the other wedge was for all the instrumentation that the performer wanted. The idea was to increase clarity and separation by having the vocals emanate from a source that was physically separate from everything else. (In other words, yes, it was a Dave Rat double-hung system, but with monitor wedges.)

After that, four buses were used by the stereo in-ears that Rylee and Cason listened to. The two sax players were back on wedges, with one box dedicated to each. The final two monitor buses were used to drive a “Texas Headphones” drumfill, which sat on both sides of the kit but was mixed in mono: One bus drove the tops, and the other bus drove the subwoofers.

Reverb and delay were critical to the onstage performance, so Jason had independent processing at his disposal. The two FX sends, added to all the monitor sends, meant that the X32 was maxed out in terms of all 16 mix buses being consumed.

Jason didn’t really get into anything DCA wise, but he did make use of mute groups. One group was to mute all the inputs, the second group was to manage vocals, and the third was to kill the FX sends easily when they weren’t needed.

Lots Of Input

Of course, we didn’t just maximize the output side of things. Pigs is a 32 input show if you count everything, including a spare.

First, there’s a block of vocal mics. It starts with Lisa on stage right, and then has Grant, Rylee, and Mike included. Cason was also going to have a vocal, but in the end that was switched out to a bari sax option.

The next three channels were dedicated to electric guitars. Normally we have two, but Marty Thomas put in the clutch performance on “Dogs,” so we needed one more. After that, we had one line for acoustic guitar.

The next nine(!) inputs were for various keys and synths. Rick had a Moog, a B3 in stereo, a Korg, and a Roland to work with. Grant uses a Micro Korg and a SubPhatty in the course of the show. The left side of the Juno was next, followed by the Nord.

The bass line came after, followed by one mic for each saxophone.

Originally, I had seven inputs reserved for drums, but Mike surprised me by deleting one tom from his shell pack. This lead to the “split Juno” situation, where between the toms and the overheads we plugged in the right side of the Juno.

Channels 29 and 30 were for the playback FX (the preshow announcement that’s actually part of the show, the crashing plane, helicopter, clocks, etc). The final two inputs were for crowd mics that we connected purely for recording purposes. Some performers like to have some ambience blended into their IEM mixes, but Rylee and Grant didn’t opt in for that on this occasion.

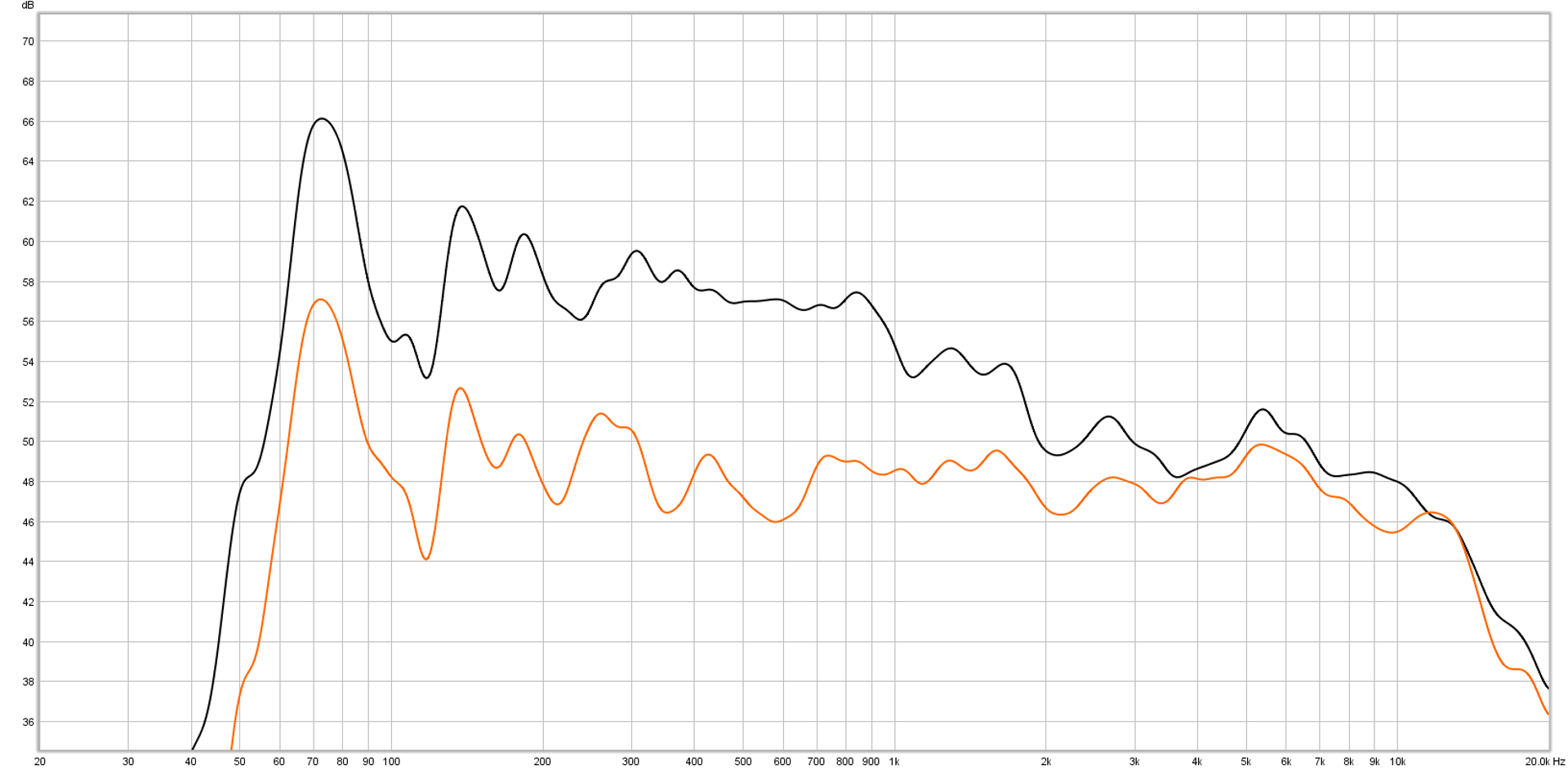

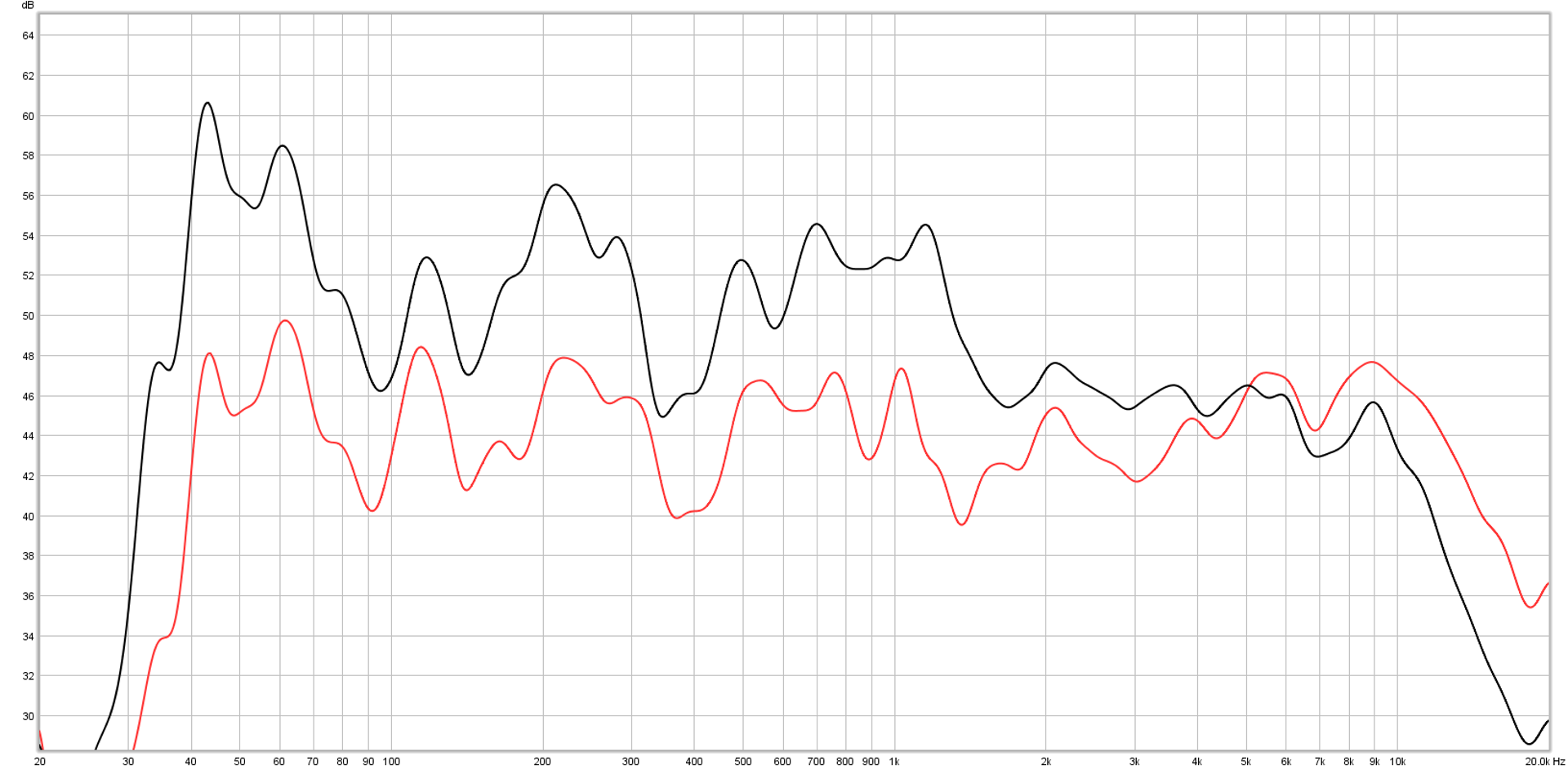

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.