An apples-to-oranges comparison still reveals a few things.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Bobby Solis of No BS Sound picked up a couple of DR110DSP loudspeakers (a new Behringer offering) for light-duty applications, and of course I wanted to get a sense of their performance. Graciously, Bobby lent me a unit and I proceeded to run test tones through both it and a reference unit – an Alto TS312, to be exact.

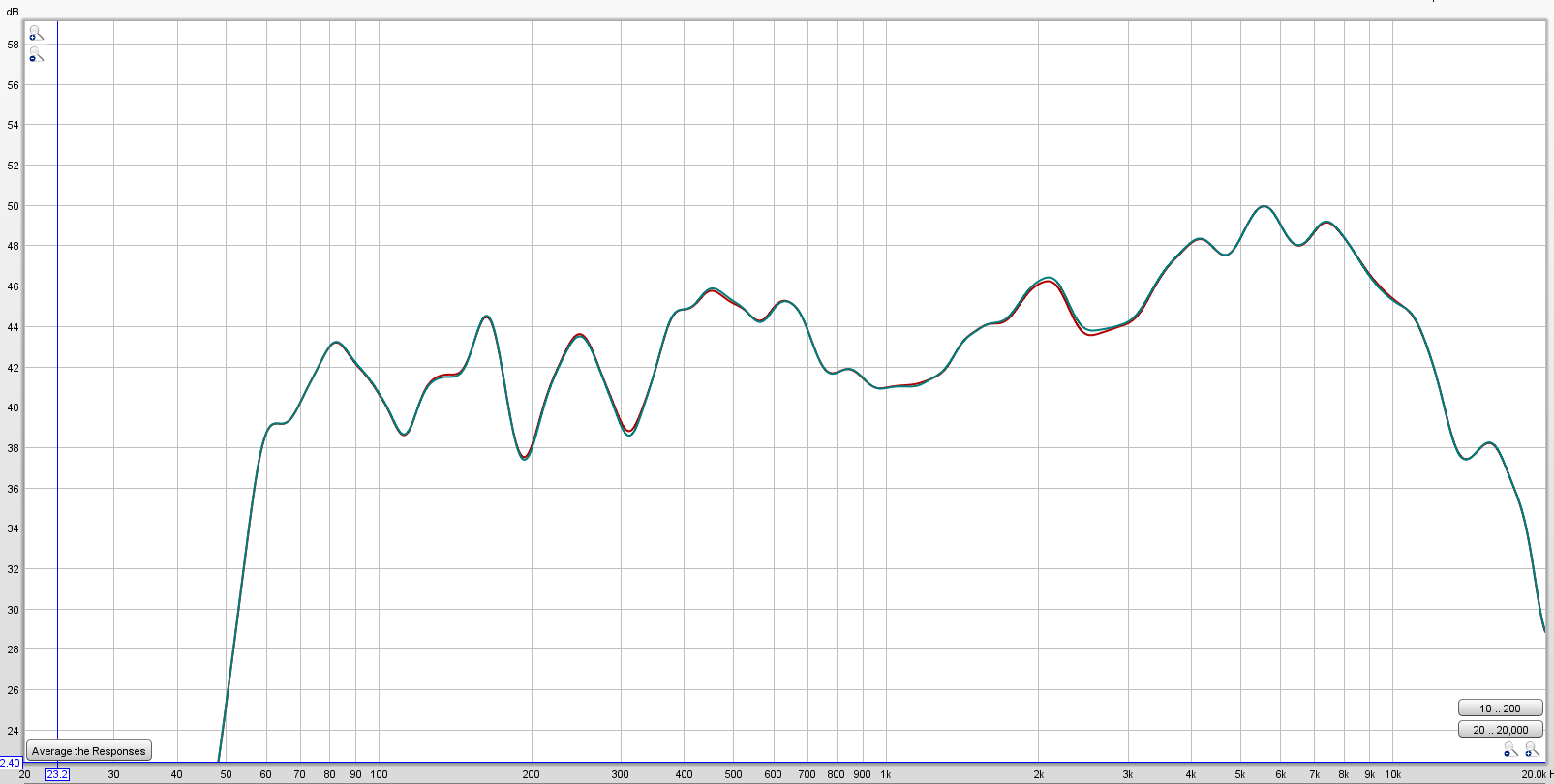

To start, I’ll say the obvious. This was an apples-to-oranges comparison. The Alto having a 12″ LF driver makes for a rather different package. Obviously, an Alto TS310 would have been a better box to have a shoot-out with, due to a closer similarity of design. Even so, we can have a conversation about the results.

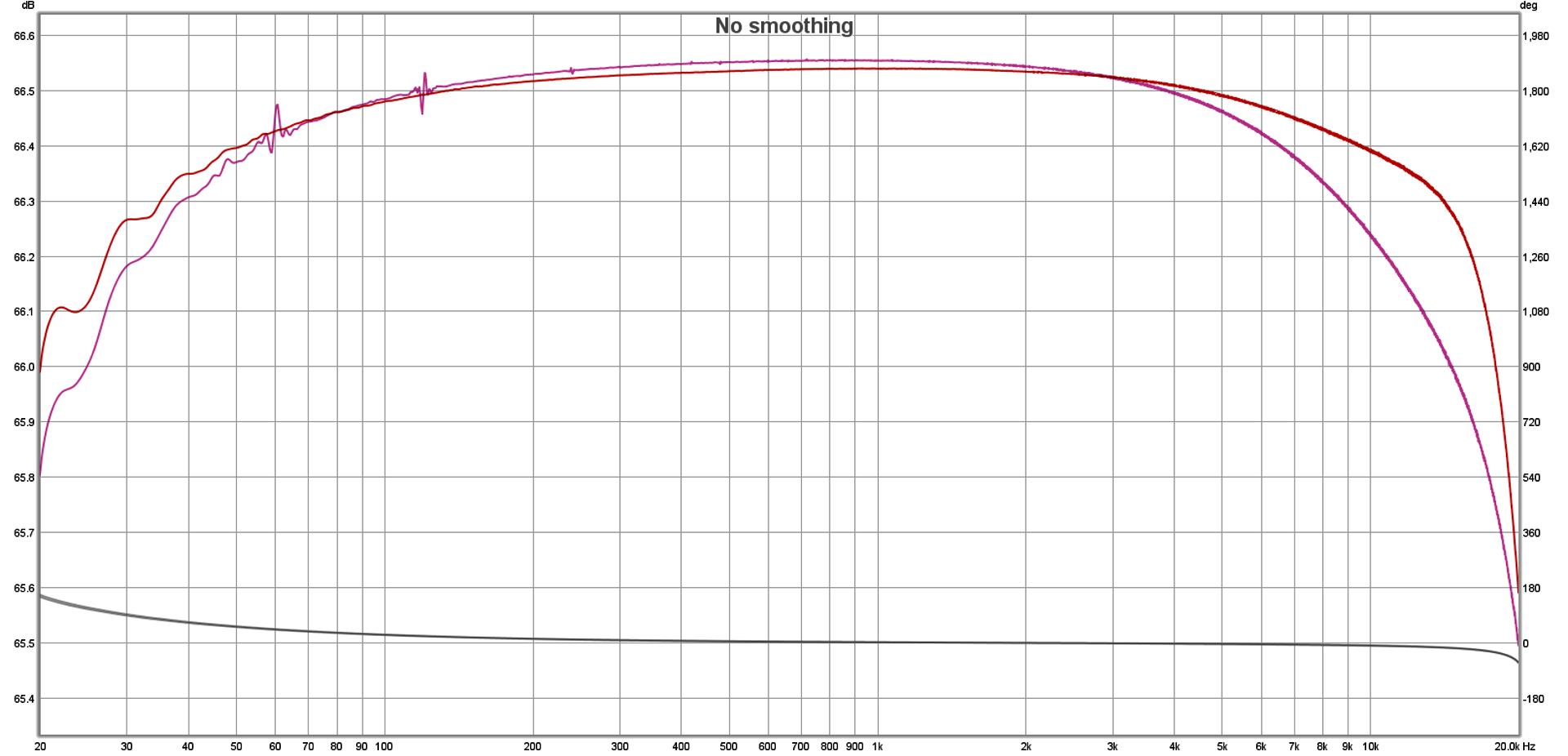

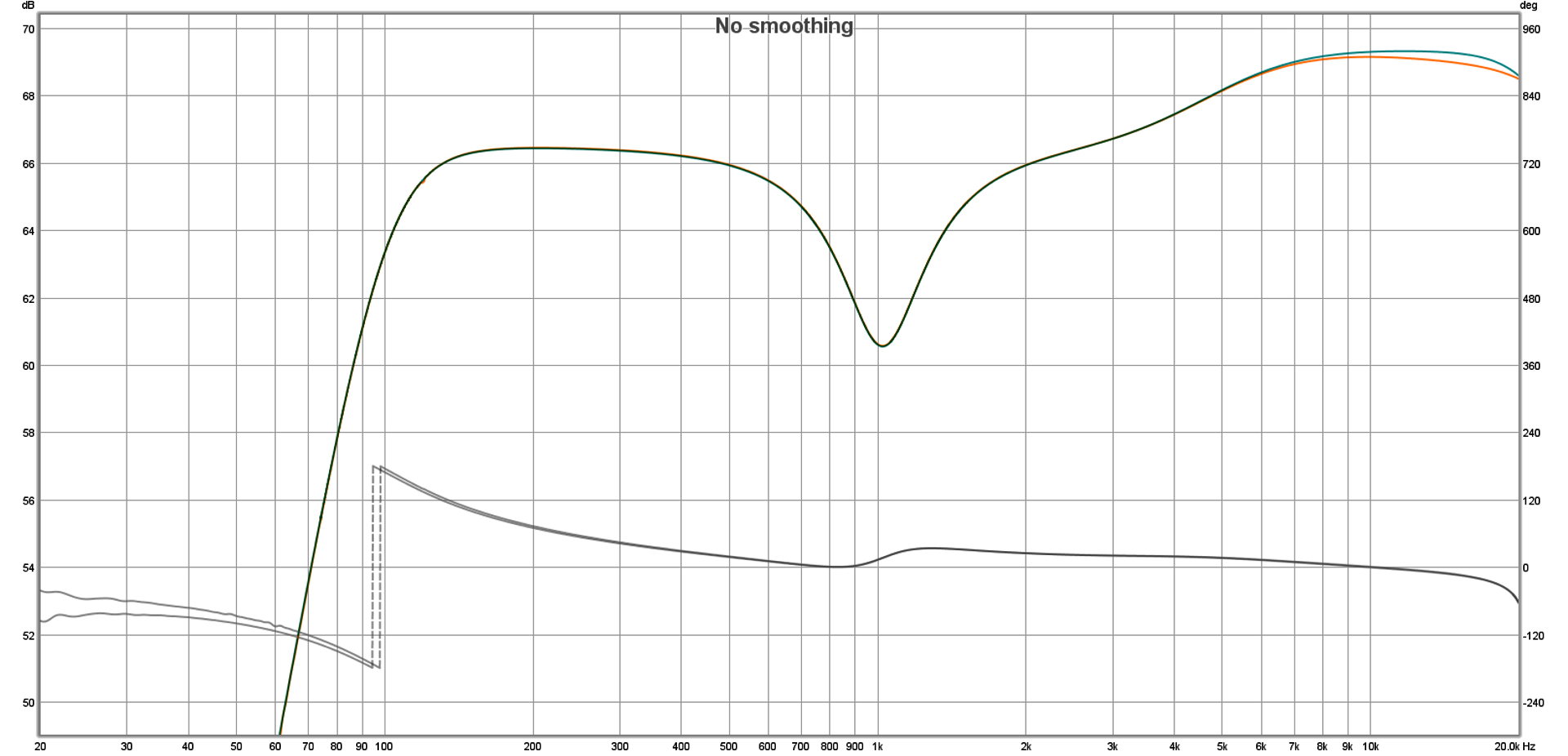

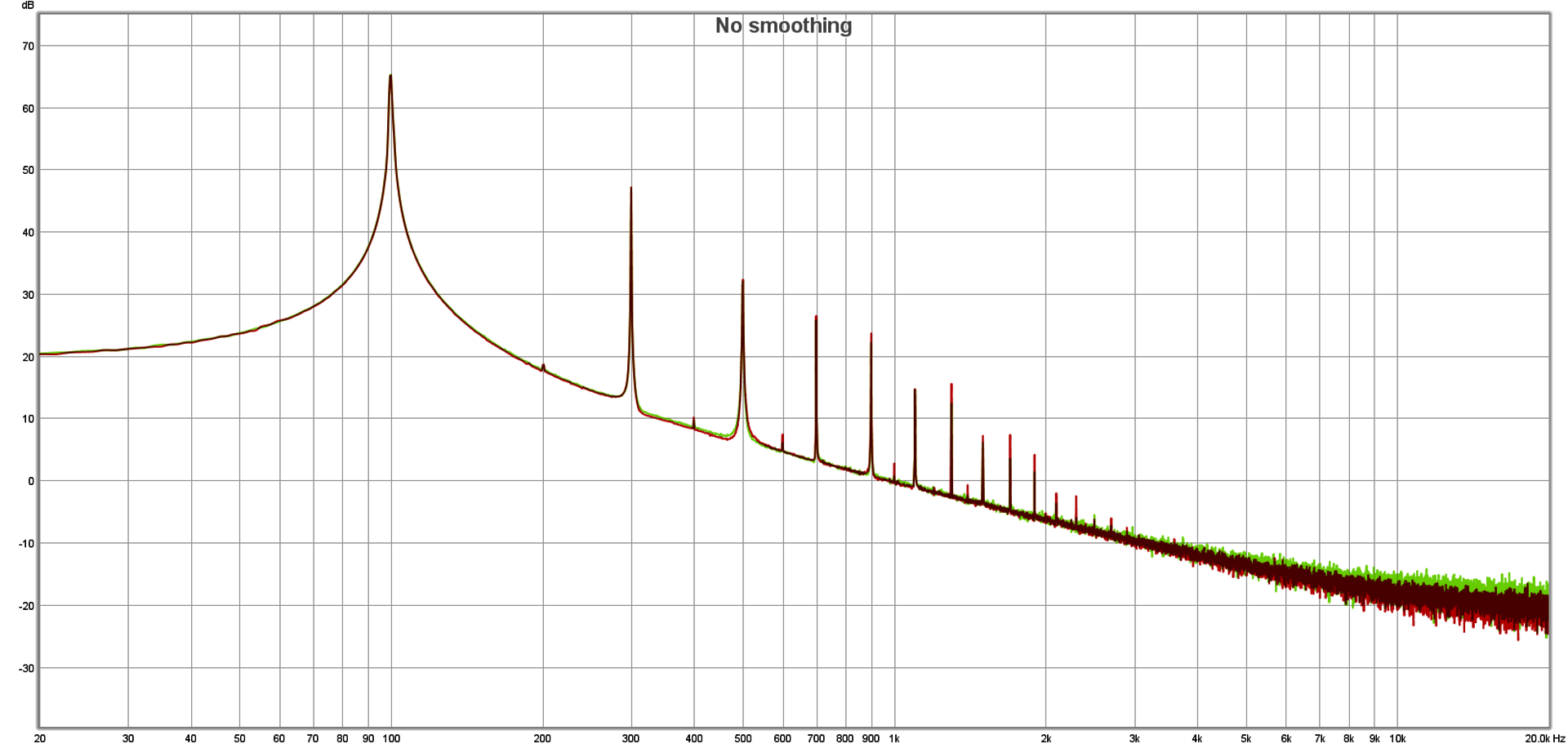

What I did for this comparison was to set up a ground-plane measurement in my garage, with the measurement mic about 10 feet from the loudspeaker grills. As best I could, I tried to find the input level on both loudspeaker units where their built-in limiters would kick in, and measured with that setting in place.

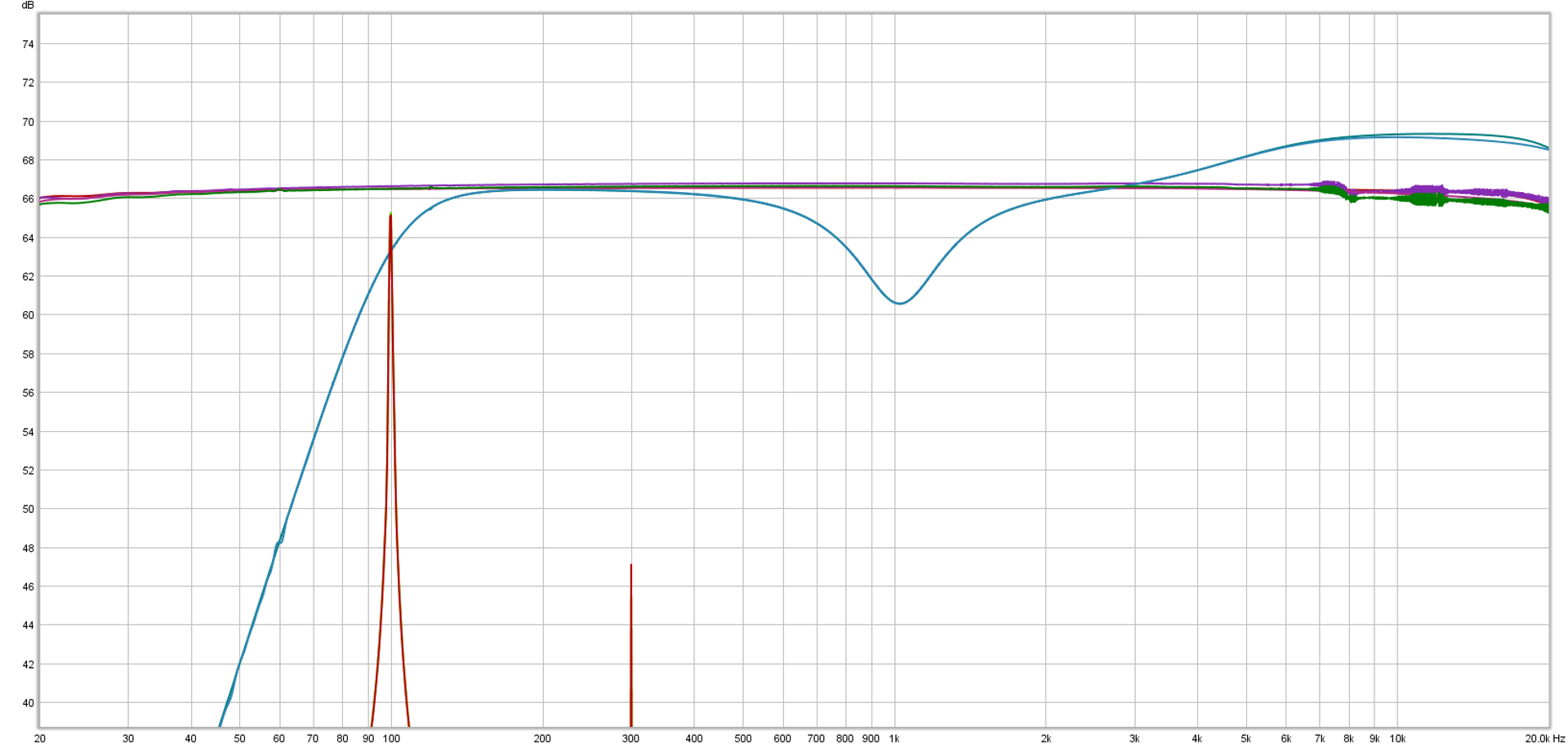

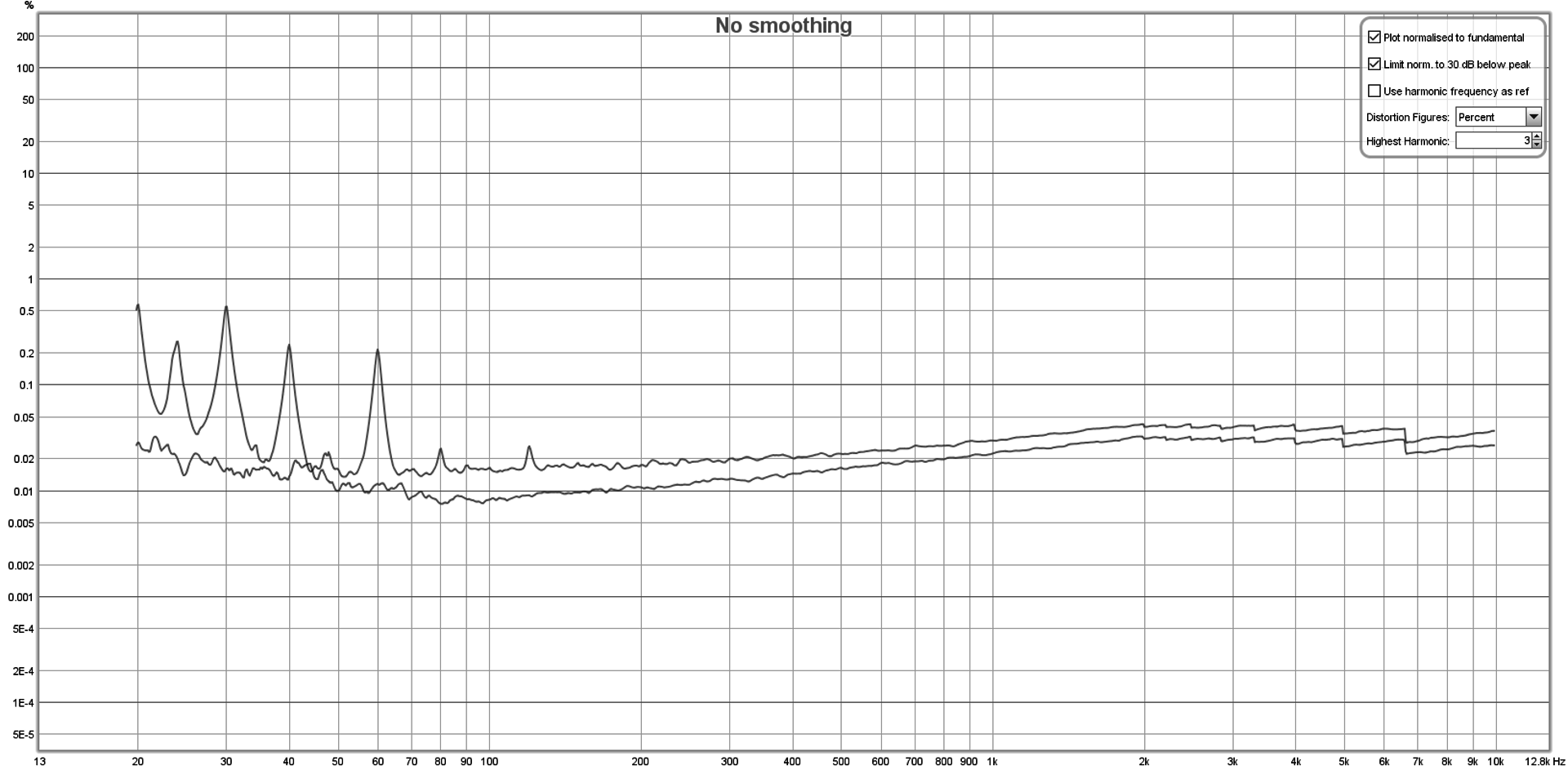

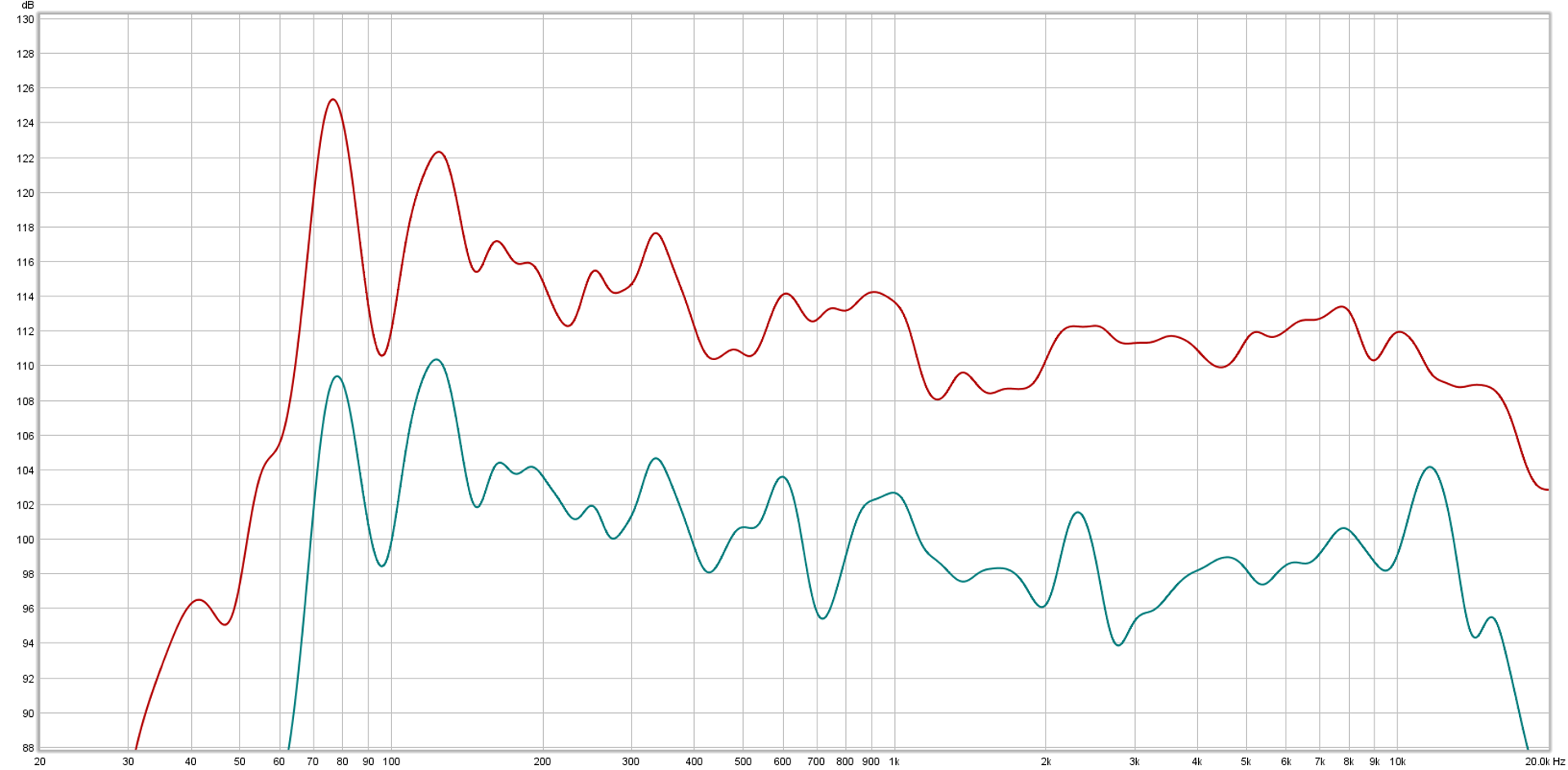

So, what did I learn from looking at the graph you can see up there?

First, a TS312 can play about 12 dB louder than a DR110DSP, on average.

Second, the DR110DSP is a bit peakier overall in its frequency response. This comports with what I hear when I use one, especially at frequencies above 1k: 2500 Hz tends to pop out, and there’s a bit of a rasp at 11 – 12 kHz. This is similar to sonic experiences I remember from the EV ZLX series, which the DR110DSP seems to be built to compete with in terms of electronics. (Interestingly, the Behringer aesthetics seems to be trying for a QSC feel.)

In terms of whizbang features, the Behringer does have a clear edge if that’s what you want. Built in Bluetooth streaming is pretty neat (and saved our bacon on a show a few days back), plus the onboard DSP offers a lot of sound-shaping options. I do appreciate having the ability to set a clearly repeatable master volume, though a continuously-variable input gain undoes that advantage a bit. An Alto TS312 is much simpler on the back panel, and some folks might see that as a disadvantage. I personally prefer my powered speakers to be a bit spartan in their control offerings, though, so the Alto fits me more readily.

So, if what you want is DSP and onboard Bluetooth, but not necessarily a ton of volume, the Behringer seems pretty okay. What I need is output and a better from-the-factory tuning, which is where the Alto leads. Even so, this evaluation was much more about curiosity than hard science. It would be interesting to find an Alto TS310 to run against the DR110DSP on a more even playing field, but I didn’t have one handy.