Going viral is neat, but you can’t count on it unless you can manage to do it all the time.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.“Going viral is not a business plan.” -Jackal Group CEO Gail Berman

There are plenty of musicians (and other entrepreneurs, not just in the music biz) out there who believe that all they need is “one big hit.” If they get that one big hit, then they will have sustained success at a level that’s similar to that of the breakthrough.

But…

Have you ever heard of a one-hit wonder? I thought so. There are plenty to choose from: Bands and brands that did one thing that lit up the world for a while, and then faded back into obscurity.

Don’t get me wrong. When something you’ve created really catches on, it’s a great feeling. It DOES create momentum. It IS helpful for your work. It IS NOT enough, though, to guarantee long-term viability. It’s a nice bit of luck, but it’s not a business plan in any sense I would agree with.

Why? Because of an assumption which I think is correct.

Consistency

In my mind, two hallmarks of a viable, long-term, entrepreneurial strategy are:

A) You avoid being at the mercy of the public’s rapidly-shifting attention.

B) Your product, and its positive effect on your business, are consistent and predictable.

Part A disqualifies “going viral” as a core strategy because going viral rests tremendously upon the whims of the public. It’s so far out of your control (as an individual creator), and so unpredictable that it can’t be relied on. It’s as if you were to try farming land where the weather was almost completely random – one day of rain, then a tornado, then a month of scorching heat, then an hour of hail, then a week of arctic freeze, then two days of sun, then…

You might manage to grow something if you got lucky, but you’d be much more likely to starve to death.

Part B connects to Part A. If you can produce a product every day, but you can’t meaningfully predict what kind of revenue it will generate, you don’t have a basis for a business. If your product is completely at the mercy of the public’s attention-span, and will only help you if the public goes completely mad over it, you are standing on very shaky ground. Sure, you may get a surge in popularity, but when will that surge come? Will it be long-term? A transient hit will not keep you afloat. It can give you a nice infusion of cash. It can give you something to build on. It can be capitalized on, but it can’t be counted on.

A viable business rests on things that can be counted on, and this is where the statistics come in. If I reduce my opinion to a single statement, I come up with this:

Long-term business viability is found within one standard deviation, if it’s found at all.

Now, what in blazes does that mean?

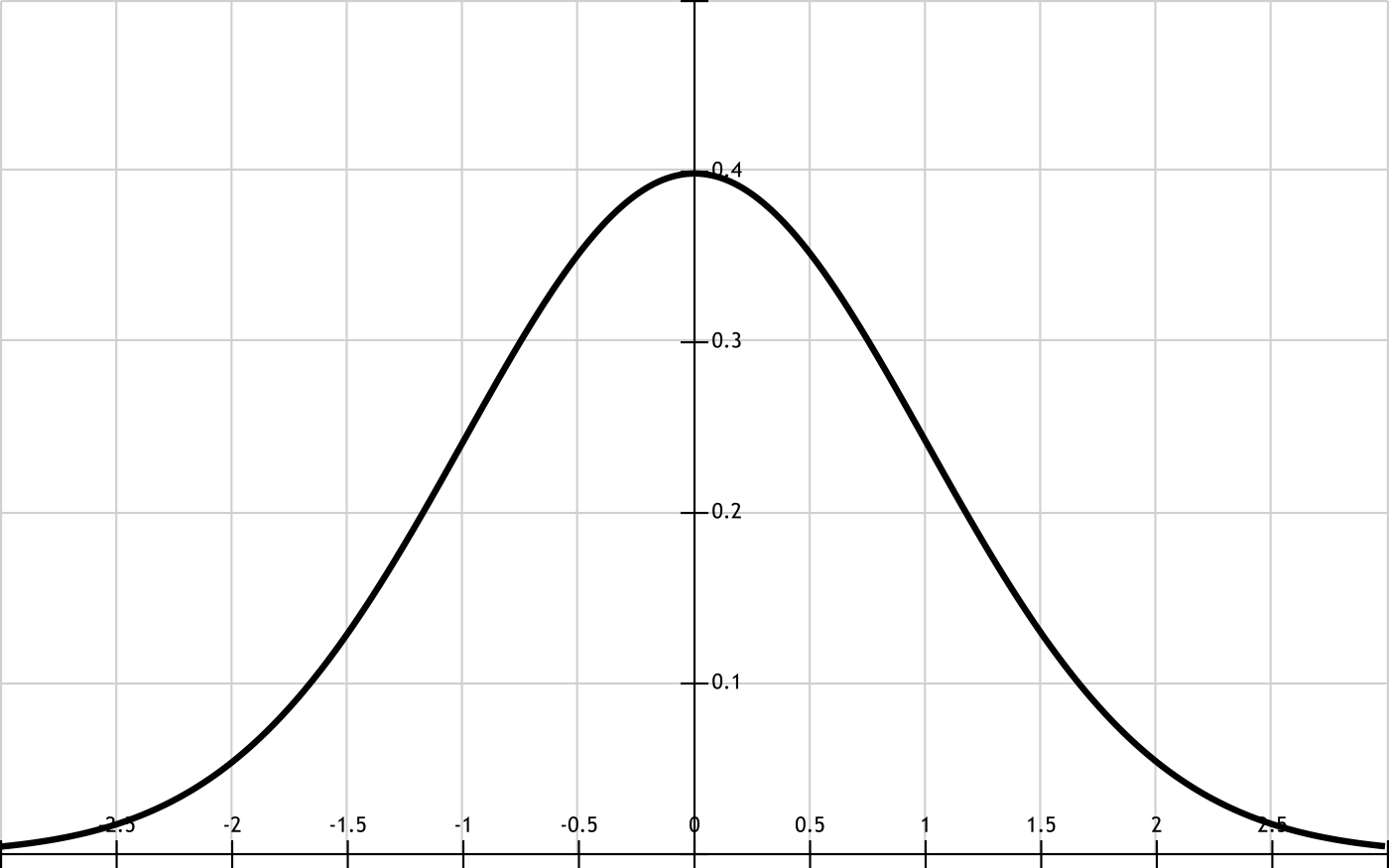

One Sigma

When we talk about a “normal distribution,” we say that a vast majority of what we can expect to find – almost all of it, in fact – will be between plus/ minus two standard deviations. A standard deviation is represented as “sigma,” and is a measure of variation. If you release ten songs, and all of them get between 90 and 110 listens every day, then there’s not much variation in their popularity. The standard deviation is small. If you release ten songs, and one of them gets 10,000 listens per day, another gets 100, another gets 20, and so on all over the map, then standard deviation is large. There are wild variations in popularity from song to song.

When I say that “Long-term business viability is found within one standard deviation, if it’s found at all,” what I’m saying is that strategy has to be built on things you can reasonably expect. It’s true that you might have an exceptionally bad day here and there, and you might also have an exceptionally good day, but you can’t build your business on either of those two things. You have to look at what is probably going to happen the majority of the time.

Do I have some examples? You bet!

I once ran a heavily subsidized (we wouldn’t have made it otherwise) venue that admitted all-ages. When it was all over and the dust settled, I did some number crunching. Our average revenue per show was $77. The standard deviation in show revenue was $64. That’s an enormous spread in value. Just one standard deviation in either direction covered a range of revenue from $13 to $141. With a variation that enormous, the only long term strategy would have been to stay subsidized. Not much money was made, and “duds” were plenty common.

We can also look at the daily traffic for this site. In fact, it’s a great example because I recently had an article go viral. My post about why audio humans get so bent out of shape when a mic is cupped took off like a rocket. During the course of the article’s major “viralness” (that might not be a real word, but whatever), this site got 110,000 views. If you look at the same length of time just before the article was published, the site got 373 views.

That’s a heck of an outlier. Even if we keep that outlier in the data and let it push things off to the high side, the average view-count per day is 162, with a standard deviation of over 2000. In that case, the very peak of the article’s viral activity is +22 standard deviations (holy smoke!) from the mean.

I can’t build a business on that. I can’t predict based on that. I can’t assume that anything else will ever do that well. I would never have dreamed that particular article would catch fire as it did. There are plenty of posts on this site that I consider more interesting, yet didn’t have that kind of popularity. The public made their decision, and I didn’t expect it.

It was really cool to go viral, and it did help me out. However, I have not been “crowned king of show production sites,” or anything like that. My day to day traffic is higher than it was before, but my life and the site’s life haven’t fundamentally changed. The day to day is back to normal, and normal is what I can think about in the long-term. This doesn’t mean I can’t dream big, or take an occasional risk – it just means that my expectations have to be in the right place: About one standard deviation. (Actually, less than that.)