If you want to experiment, small venues are a great place to be.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

“The Uncanny Valley” is something that you might not be familiar with. It’s the idea that, as humans, we become more and more comfortable with creatures and machines as they look more and more like us – until a certain point. Rather suddenly, a machine or animal reaches a point where it’s very human-like, and yet not human enough. We unconsciously interpret the thing as being a physically or mentally damaged person, and so we’re repulsed by it. Climbing out of the uncanny valley requires that the object of our horror become so lifelike that we can’t readily tell the difference between it and an actual human.

The reason The Uncanny Valley has its name is that, when you graph the above phenomenon, the “person is comfortable with the object” line climbs steadily, and then drops into something of a chasm before recovering.

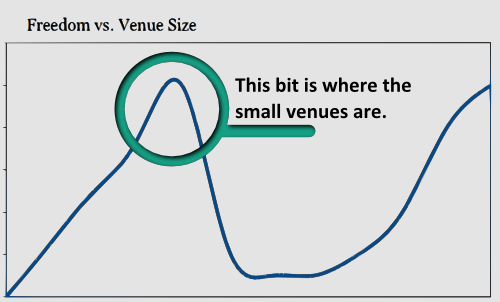

What I’ve started to notice in the past years is that Uncanny Valleys are actually pretty easy to find. One of these valleys exists in the area of an audio human’s freedom to experiment and try new things. You might think that an audio tech’s ability to explore new techniques increases in a simple, linear fashion as venue size increases – but that’s not actually true.

There’s actually a huge downward slope in the “freedom” graph for sound persons, and it happens right after the curve leaves small-venue territory. As far as I can tell, anyway.

No Riders Means More Leeway

But why would this be the case? Why would small venues actually have the potential for more experimentation by a noise wrangler?

By my estimation, it all has to do with being in a spot that’s just right for doing things that are a bit out of the mainstream. To be in that spot, the venue has to be big enough for expanded system functionality and (or) advanced applications to actually matter, while being small enough that acceptability to the widest range of acts isn’t a major factor.

…yeah, that was kinda unwieldy. Let me make this a little more concrete.

Most mixing consoles that are widely used are either analog units – where the control surface is directly tied to the circuitry – or digital mixers that simulate this behavior to some degree. In defiance of these conventions, I use a semi-homebrew console that has no traditional control surface at all.

The industry standard stage-vocal mic is the SM-58. I don’t particularly care for the SM-58, and I’m not really wild about any other offering from Shure, and so my go-to mics for onstage singers are models from EV and Sennheiser. They’re mics that I’m interested in, at a personal level.

I could never get away with this if I worked at a mid-size venue.

The reason that I CAN experiment and do what I want in the small-venue environment is because I don’t have to conform to the expectations of acts that need wide compatibility and high predictability. As a guy that works primarily with local musicians, I don’t have to contend with concert riders that make demands for industry standard gear. I also don’t have to worry about ensuring the productivity of a large number of visiting audio humans.

Most of my locals don’t even HAVE a written list of production requirements. If they did, though, it would probably read:

“It would be great if you have two vocal mics available. If you have 3 vocal mics, that would be even better. We don’t care what the vocal mics are, as long as they basically sound like what they’re pointed at and don’t smell like the hippo enclosure at the zoo. If you’ve got mics, then we hope you also have a couple of speakers to point at the audience, and one or two to point back at us. Hopefully they’re okay to listen to and not ready to spontaneously combust. See you on Friday night.”

There’s a lot of freedom in there, because there aren’t a lot of specifics. When you get into bigger venues whose bread and butter is hosting regionals and smaller nationals, things suddenly change. The riders start to say things like:

“Must have 4 Beta-series Shure mics available.”

“Console must be functionally equivalent to a Soundcraft GB4-32.”

“No Peavey, Behringer, A&H, or Mackie.”

…and so on.

To do your job properly, you simply can’t be scratching your own itches and trying oddball solutions. You have to be ready to cater to a lot of people who need to walk up to something they can predict and be comfortable with immediately, and that means lots of “industry standard midgrade-pro” gear.

Let me be clear: There’s nothing wrong with working for a venue or provider who’s target market is the regional and national act. It’s a career path that can be very exciting and enjoyable. It’s just good to know what the expectations are.

Climbing Out Of The Valley

The audio-dude freedom curve does come back up eventually. For proof of this, see Dave Rat. When you get to the level of Dave Rat and his peers, your freedom for experimentation returns. The reason for this is twofold:

1) You are now trusted enough as a craftsperson, and are regarded as enough of a leader for people to put their faith in your experiments. You’re hired specifically to be you, as opposed to being hired because you can make audio gear work. (There is a difference.)

2) You have the resources necessary to execute your experiments in a nicely crafted way, where the fit, finish, and performance are at the caliber necessary for the acts that hire you.

There’s a certain level that you can get to where YOU are the one who writes up all the requirements. When you get to that stage, you can have all the crazy-cool notions you want. It becomes your job to have those notions and bring them to fruition, and so your “freedom curve” climbs higher and higher.

It’s important to note that “the curve” isn’t the same for everyone. For in-house audio humans, the freedom curve drops off after the small-venue scale, and then never recovers. For guys and gals that provide complete rigs for acts, the curve can have all kinds of peaks and dips. For folks that mix with their own front ends on other people’s systems, the curve can be pretty flat.

The bottom line is to figure out what excites you as an audio tech, and find a groove that works for you. If you love to do your own thing, buck the trends, and push the envelope, you can have a lot of fun in small venues.