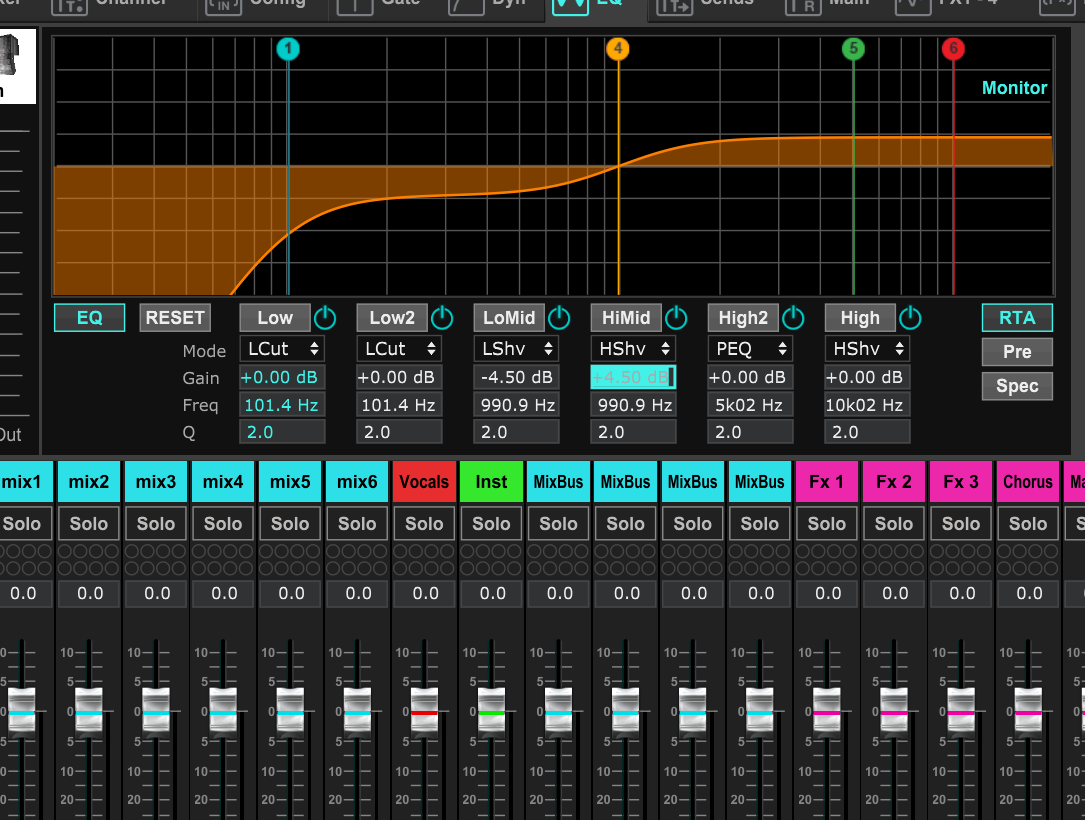

I’m learning that shelving filters are very handy for system tuning.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

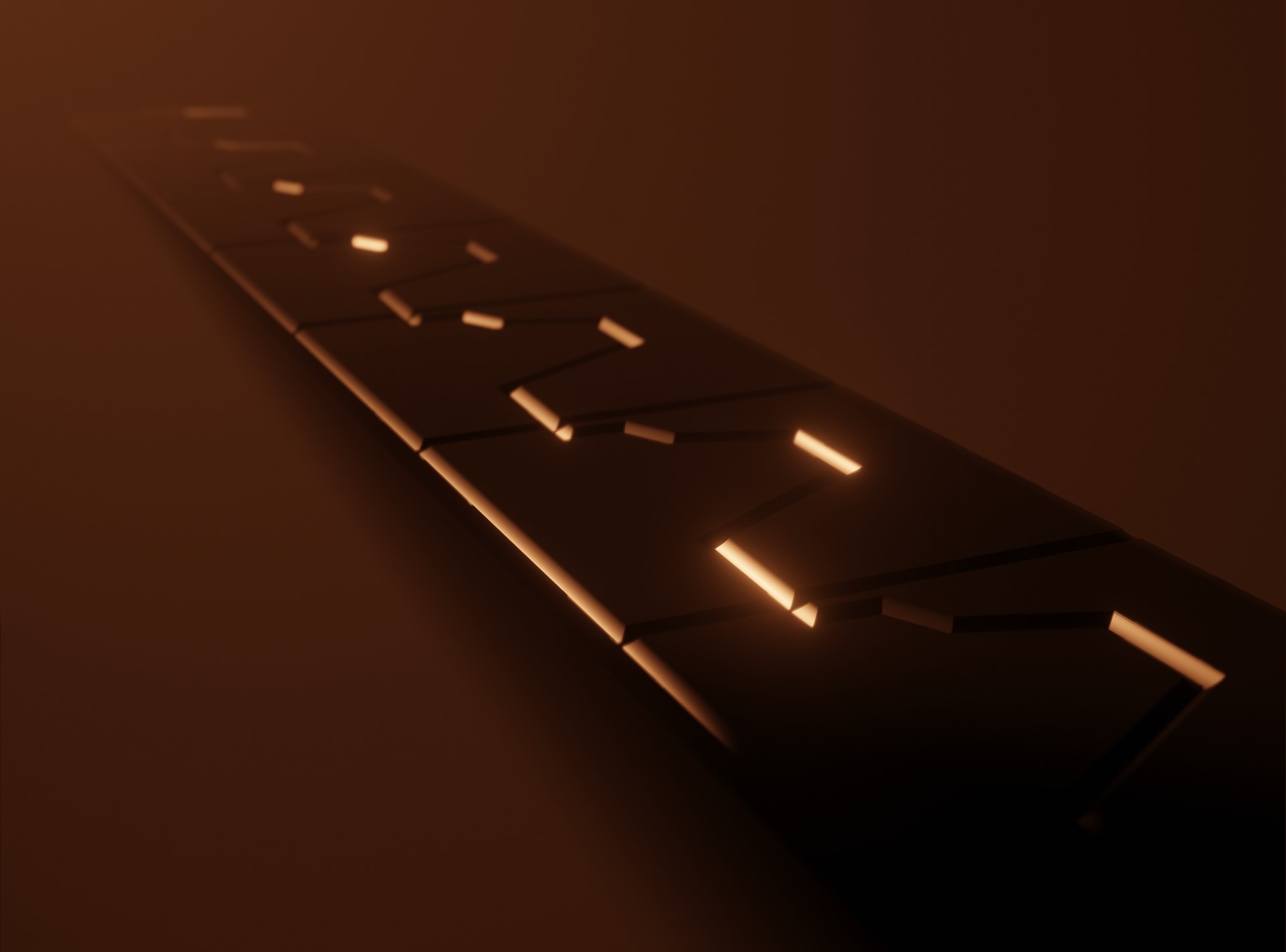

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.I used to shy away from shelving filters. I mean, why sledgehammer away at something when you can perform parametric surgery? It’s better, right?

As I’ve done more and more work with system tuning, though, I’ve started to become better at imagining the filters that will produce a desired response. It’s a bit like those characters in The Matrix that could “see the code.” You begin to recognize that, oh yeah, an octave-wide parametric at 1250 Hz could get that peak under control.

I’ve also become better at understanding how obsessive microsurgery is rarely a good place for an audio human to start. The broad-brush response is far more important as a launch point.

And I’m noticing more and more, especially with powered loudspeakers that are well-tuned at the factory, that a bit of opposed “tilt” in the lows and highs does A LOT. With two filters and a few seconds, a great deal of garble goes away – and a pleasant clarity also becomes noticeable. I’ve used the method at FOH and in monitor world, and it has made me smile in both places.

The neat thing about shelving EQ is that it can affect a very broad range of frequencies very evenly. Depending on the filter design, after about an octave’s worth of transition, every frequency in the filter’s passband gets the same treatment. It’s markedly different from a pass/ cut filter that effectively does more and more as you move into its area of operation. It’s also noticeably distinct from a peaking filter that falls off as you leave its center frequency. Shelving is a unique sort of tone shaping, and I’m glad that I’m finally starting to appreciate its particular flavor. It’s not a sledgehammer at all! It’s more of a very evenly distributed push.

It’s not that peaking filters are now useless to me, either. I still love them. They’re very handy for fixing spot problems, like a raspy peak in the highs. That’s the thing, though: I get to reserve them for fine-grained tweaks, rather than pressing them into a kind of service that a different filter is better for. Why approximate a shelving EQ with a peaking filter? Why not just use the shelving filter?

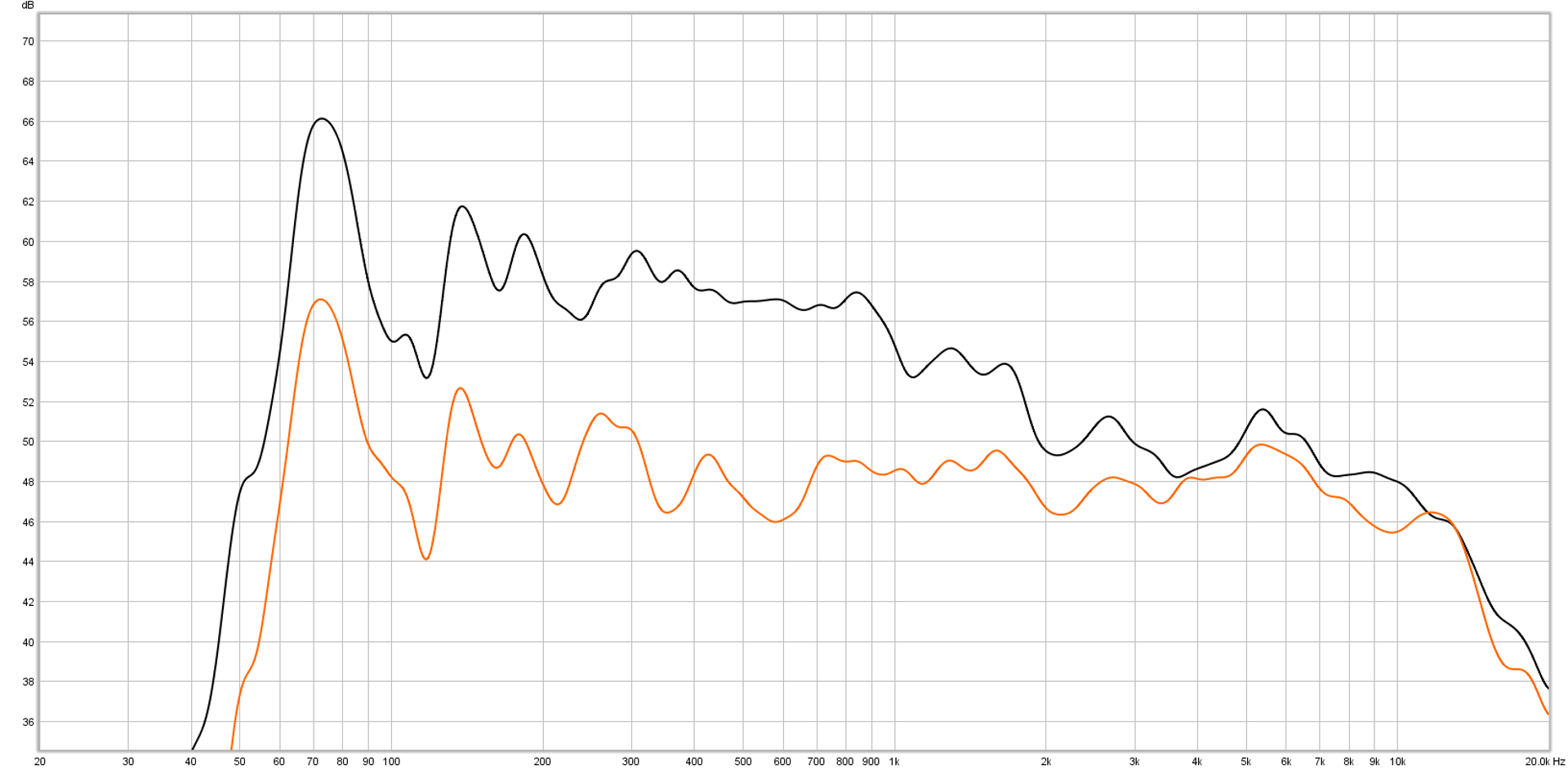

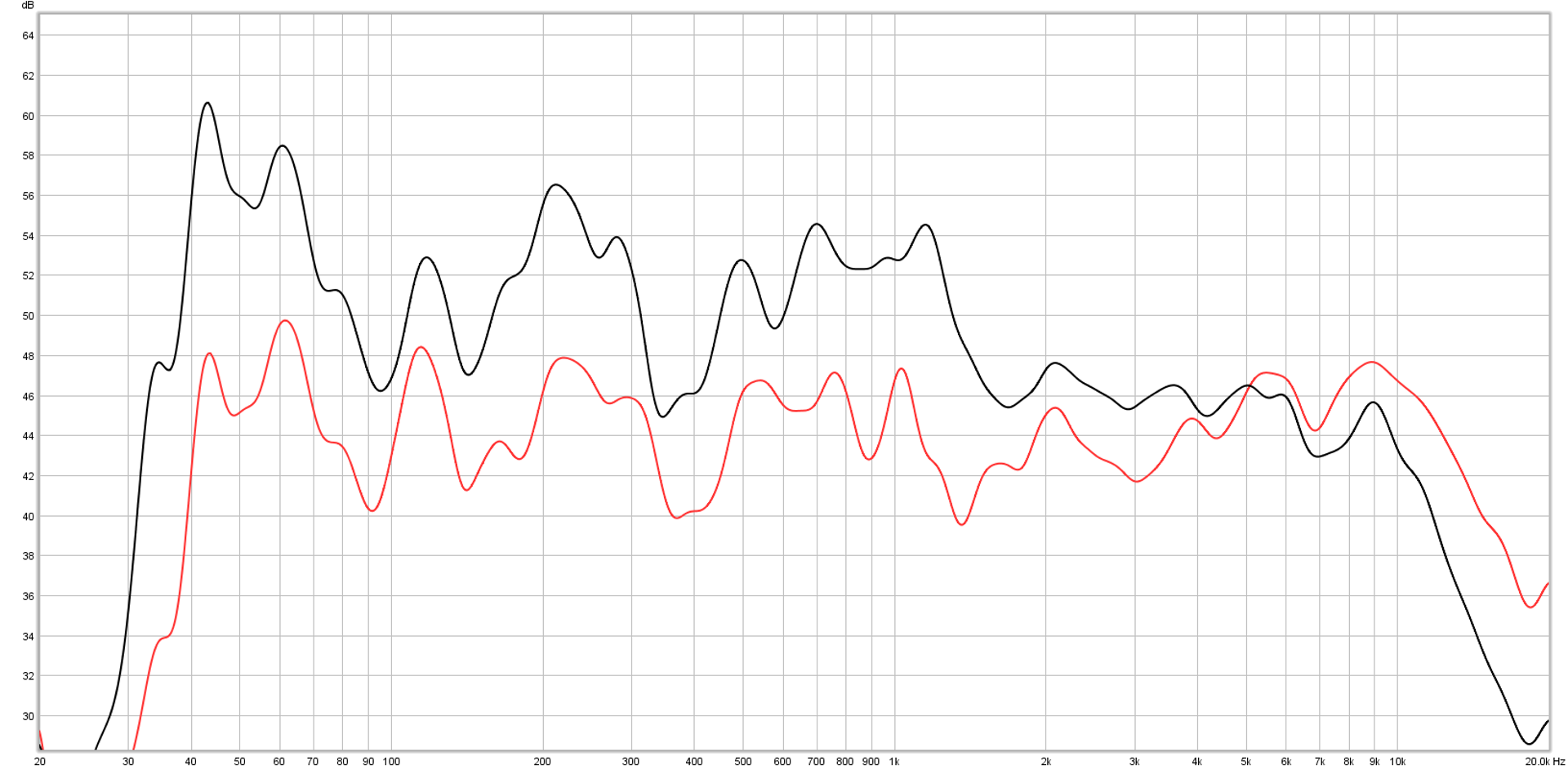

If you have the inclination, and flexible shelving filters you can apply to an output, try this yourself: Run a quick measurement of a system, and then try to find the spot in the trace that the response seems to “hinge” around. The place where, if you applied opposed shelving EQs, the resulting response would be essentially aligned throughout the loudspeaker’s normally usable range. Statistically flat; Balanced peaks and valleys in both the low-end and high-end. (When you see the traces and hear the results, you’ll know what I mean.)

You might be surprised at just how quickly and easily you can get a system to sound much more well-behaved using this method. Obviously, it isn’t going to work everywhere and with every system, but I think it’s well worth looking into.