If you don’t need it, don’t spend power (or volume) on it.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

For loudspeakers, a crossover is used to separate full-range audio into multiple “passbands,” with each passband being appropriate for a certain enclosure or driver. For instance, there’s no need to send a whole bunch of high-frequency information to a large-diameter speaker if you’ve also got a handy device that’s better for top-end. On the flipside, failing to filter low-frequency information is a good way to wreck a “meant for HF” output transducer.

A beautifully implemented crossover creates a smooth transition from box to box and driver to driver. Crossovers can also help with getting the maximum performance out of an amplifier/ loudspeaker chain – again, because pushing material to a driver that can’t reproduce it is a waste of power.

Most of the time, we think of a crossover as an electrical device. Whether the filter network is a bunch of passive components at the end of a speaker cable, or a DSP sitting in front of the amplifiers, the mental image of a crossover is that of a signal processor.

…but remember how I’ve talked about acoustical resonant circuits? The reality of the pro-audio life, especially in small rooms, is that the behaviors of electrical devices show up in acoustical form all the time. In the past few years, I’ve found that creating acoustical crossovers between the stage wash and the FOH (Front of House) PA can be incredibly useful.

Why This Matters In Small Rooms

In a small venue, you don’t always have a lot of power to spare. It’s rarely practical to deploy a PA system that can operate at “nothing more than a brisk walk” for most of the show. Instead, you’re probably using a LOT of the audio rig’s capability at any given time.

Even if you have a good deal of power to spare, you often don’t have very much volume to spare. A small venue gets loud in a big hurry – not only because of acoustics, but because the average audience member is “pretty dang close” to the stage and PA.

Taken together, these issues present hat-explodingly good reasons to avoid chewing up your power and/ or SPL budget with audio that you just don’t need. Traditionally, dealing with this has taken the form of not reinforcing entire sources or channels. (This can oftentimes, and unfortunately, be appropriate. I’ve done several shows where one person was so loud that everyone EXCEPT them was in the PA.) An “all-or-nothing per channel” approach is sometimes a bit too much, though. What can be better is to use powerful and dramatic, yet judiciously applied subtractive EQ.

Aggressive Filtration

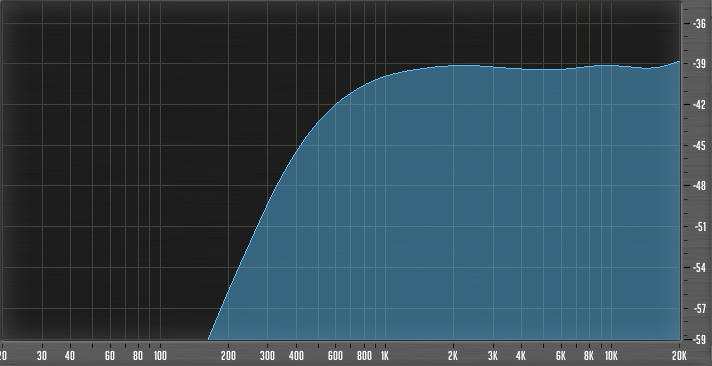

A good way to illustrate what I mean by “powerful and dramatic, yet judiciously applied subtractive EQ” is to show you some analysis traces. For instance, here’s my starting point for a vocal HPF (High Pass Filter):

The filter frequency is 500 Hz. Effectively, I’m chucking out everything at or below about 250 Hz.

“But, doesn’t that sound really thin,” you ask?

Indeed, it does sound a bit thin at times. If I don’t have a lot of monitor wash, or the singer doesn’t have a voice that’s rich in low-mid, or if they just don’t want to get right up on the mic, then I need to roll my filter down. On the other hand, in situations where the monitors were loud, the vocalists had strong voices, and they had their lips stuck to the mics, I’ve had HPF filters up as high as 1 kHz or more.

The point is that the stage-wash often gives me everything I need for low-mid in the vocals, so why duplicate that energy in the FOH PA? If I create a nice transition between the PA and what’s already in the room, I only have to spend power on what I need for clarity.

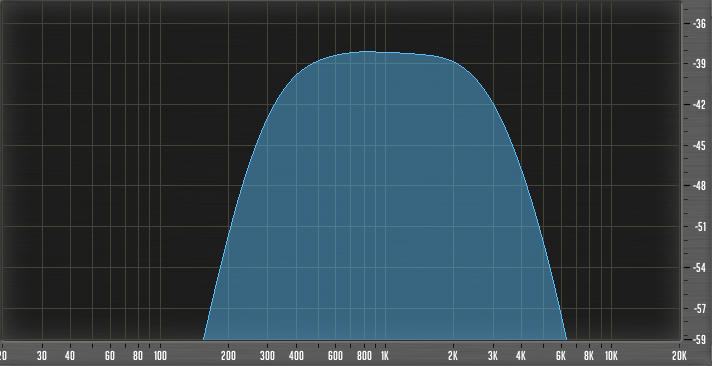

Now, here’s a trace for a guitar amp:

Of course, you don’t necessarily need something as extreme as this all the time. What’s great about filtering a guitar like this, though, is that you’ve thrown away everything except the “soul” of the instrument – 400 Hz to 2 kHz. Especially with “overly scooped” guitar sounds, what you need for the guitar to actually sit in the live mix is more midrange than what you’re getting. Of course, you could turn up the ENTIRE guitar to get what you need – but why? You’ll be killing the audience. It’s much better to “just turn up the mids” without turning up anything else.

…and even if the guitar is only really in the PA during solos, this kind of filter can still be a good thing to implement. If you have to REALLY get on the gas for a lead part, you can avoid tearing people’s heads off with piercing high end – as well as avoid stomping all over the rhythm player and the bassist.

By combining a highly filtered sound with the stage volume, you effectively get to EQ the guitar without having to completely overwhelm the natural sound from the amp. (This is just an acoustical version of what multiband equalizers do anyway. You select a frequency range to work on, and everything else is left alone. Whether this happens purely with electrical signals or in combination with acoustic events is relevant, but ultimately a secondary issue.)

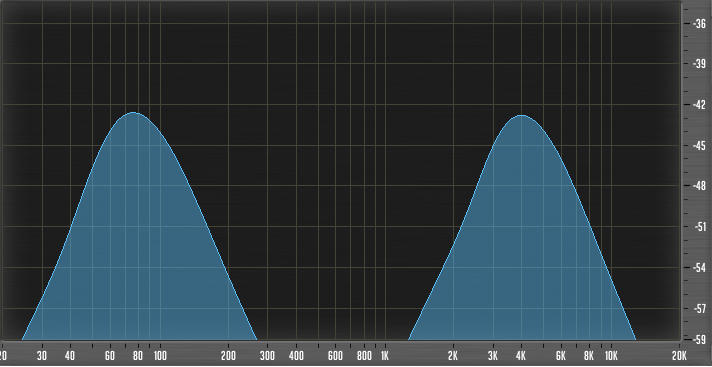

Now, how about a kick drum?

Again, this kind of thing isn’t appropriate in all contexts. You wouldn’t do this for a jazz gig…but in a LOT of other situations, what you need from the kick drum is “thump” and an appropriately placed “pop” or “click.”

And that’s it.

In a small venue, reproducing much of a rock or pop kick’s midrange is unhelpful. All you do is run over everything else, which makes you turn up everything else, which makes your whole mix REALLY LOUD.

Instead, you can create an acoustical crossover to sweeten the kick “just enough,” without getting any louder than necessary.

All Wet

Saving power and volume also applies for situations where you want effects to come from the PA. It’s very easy to get too loud when you want to put reverb, delay, or even chorus on something. The reason for this is because these effects have a “dry” (unprocessed) component, that has to be blended properly with the “wet” sound. What can happen, then, is that you end up pushing the entire sound up too far – because you want to hear the effects. The “dry” sound in the signal combines with the “dry” sound in the room, which makes for an acoustical result that isn’t as “wet” as you wanted…so, you push the volume until the “dry” sound through the PA overwhelms the sound in the room.

That can be pretty loud.

Instead of brute force, though, you can just tilt the “wet” ratio much further in favor of the effect.

In fact, I’ve been in some situations where, say, a snare drum was in exactly the right place without any help from the PA. In that case, I set up my routing so that the snare reverb was 100% wet – no “dry” signal at all. I already had all the “dry” sound I needed from the snare in the room, and so I just turned up the “all wet” reverb until the total, acoustical result was what I wanted.

The bottom line with all this is that, in a small space, you can get pretty darn decent sound without a screaming-loud PA. You just have to use the sound that you already have, and very selectively add the bits that need a little help. The more fine-grained you can be with the creation of this acoustic crossover, the more you can bend the total acoustical result to your will…within reason, of course.