This site is mostly about live audio, and as such, I talk about feedback a lot. I’m used to the idea that everybody here has a pretty good idea of what it is.

But, every so often, I’ll do a consulting gig and be reminded that feedback can be a mysterious and unknown force. So, for those of you who are totally flummoxed by feedback monsters, this article exists for your specific benefit.

All Locations Harbor Dragons

The first thing to say is this: Any PA system with real mics on open channels, and in a real room, is experiencing feedback all the time. Always.

Feedback is not a phenomenon which appears and disappears. It may or may not be a problem at any particular moment in time. You may or may not be able to hear anything like it at a given instant. Even so, any PA system that is doing anything with a microphone is guaranteed to be in a feedback loop.

What matters, then, is the behavior of the signal running through that loop. If the signal is decaying into the noise floor before you can notice it, then you DO have feedback, but you DON’T have a feedback problem. If the signal is dropping slowly enough for you to notice some lingering effects, you are beginning to have a problem. If the signal through the feedback loop isn’t dropping at all, then you are definitely having a problem, and if the looped signal level is growing, you have a big problem that is only getting bigger.

Ouroboros

If every PA system is a dragon consuming its own tail – an ouroboros – then how does that self-consuming action take place?

It works like this:

1) A sound is made in the room.

2) At least one microphone converts that sound into electricity.

3) The electricity is passed through a signal chain.

4) At the end of the chain is the microphone’s counterpart, which is a loudspeaker.

5) The loudspeaker converts the signal into a sound in the room.

6) The sound in the room travels through direct and indirect paths to the same microphone(s) as above.

7) The new sound in the room, which is a reproduction of the original event, is converted into electricity.

The loop continues forever, or until the loop is broken in some way. The PA system continually plays a copy of a copy of a copy (etc) of the original sound.

How Much Is The Dragon Being Fed?

What ultimately determines whether or not your feedback dragon is manageable or not is the apparent gain from the microphone’s reference point.

Notice that I did NOT simply say “the gain applied to the microphone.”

The gain applied to the microphone certainly has a direct and immediate influence on the apparent gain from the mic’s frame of reference. If all other variables are held constant, then greater applied gain will reliably move you closer toward an audible feedback issue. Even so, the applied gain is not the final predictor of ringing, howling, screeching, or any other unkind noise.

What really matters is the apparent gain at the capsule(s).

Gain in “absolute” terms is a signal multiplier. A gain of 1, which may be referred to as “unity,” is when the signal level coming out of a system (or system part) is equal in level to the signal going in. A signal level X 1 is the same signal level. A gain of less than 1 (but more than zero) means that signal level drops across the in/ out junction, and a gain of greater than 1 indicates an increase in signal strength.

A gain multiplier of zero means a broken audio circuit. Gain multipliers of less than zero are inverted polarity, with the absolute value relative to 1 being what determines if the signal is of greater or lesser intensity.

Of course, audio humans are more used to gain expressed in decibels. A gain multiplier of 1 is 0 dB, where the input signal (the reference) is equal to the output. Gain multipliers greater than 1 have positive decibel values, and negative dB values are assigned to multipliers less than 1. “Negative infinity” gain is a multiplier of 0.

The apparent gain as referenced by the pertinent microphone(s) is what can also be referred to as “loop gain.” The more the reproduced sonic event “gets back into” the mic, the higher that loop gain appears to be. The loop gain is applied at every iteration through the loop, which each iteration taking some amount of time to occur. If the time for a sonic event to be reproduced and arrive back at the capsule is short, then feedback will build aggressively when the loop gain is positive, but also drop quickly when the loop gain is negative.

Loop gain, as you might expect, increases with greater electronic gain. It also increases as a mic’s polar pattern becomes wider, because the mic has greater sensitivity at any given arrival angle. Closer proximity to a source of reproduced sound also increases apparent gain, due to the apparent intensity of a sound source being higher at shorter distances. Greater room reflectivity is another source of higher loop gain; More of the reproduced sound is being redirected towards the capsule. Lastly, a frequency in phase with itself through the loop will have greater apparent gain than if it’s out of phase.

This is why it’s much, much harder to run monitor world in a small, “live” space than in a large, nicely damped space – or outside. It’s also why a large, reflective object (like a guitar) can suddenly put a system into feedback when all the angles become just right. The sound coming from the monitor hits the guitar, and then gets bounced directly into the most sensitive part of the mic’s polar pattern.

Dragon Taming

With all that on the table, then, how do you get control over such a wild beast?

Obviously, reducing the system’s drive level will help. Pulling the preamp or send level down until the loop gain becomes negative is very effective – and this is a big reason for bands to work WITH each other. Bands that avoid being “too loud for themselves” have fewer incidences of channels being run “hot.” Increasing the distance from the main PA to the microphones is also a good idea (within reason and practicality), as is an overall setup where the low-sensitivity areas of microphone polar patterns are pointed at any and all loudspeakers. In that same vein, using mics with tighter polar patterns can offer a major advantage, as long as the musicians can use those mics effectively. Adding heavy drape to a reflective room may be an option in some cases.

Of course, when all of that’s been done and you still need more level than your feedback monster will let you have, it’s probably time to break out the EQ.

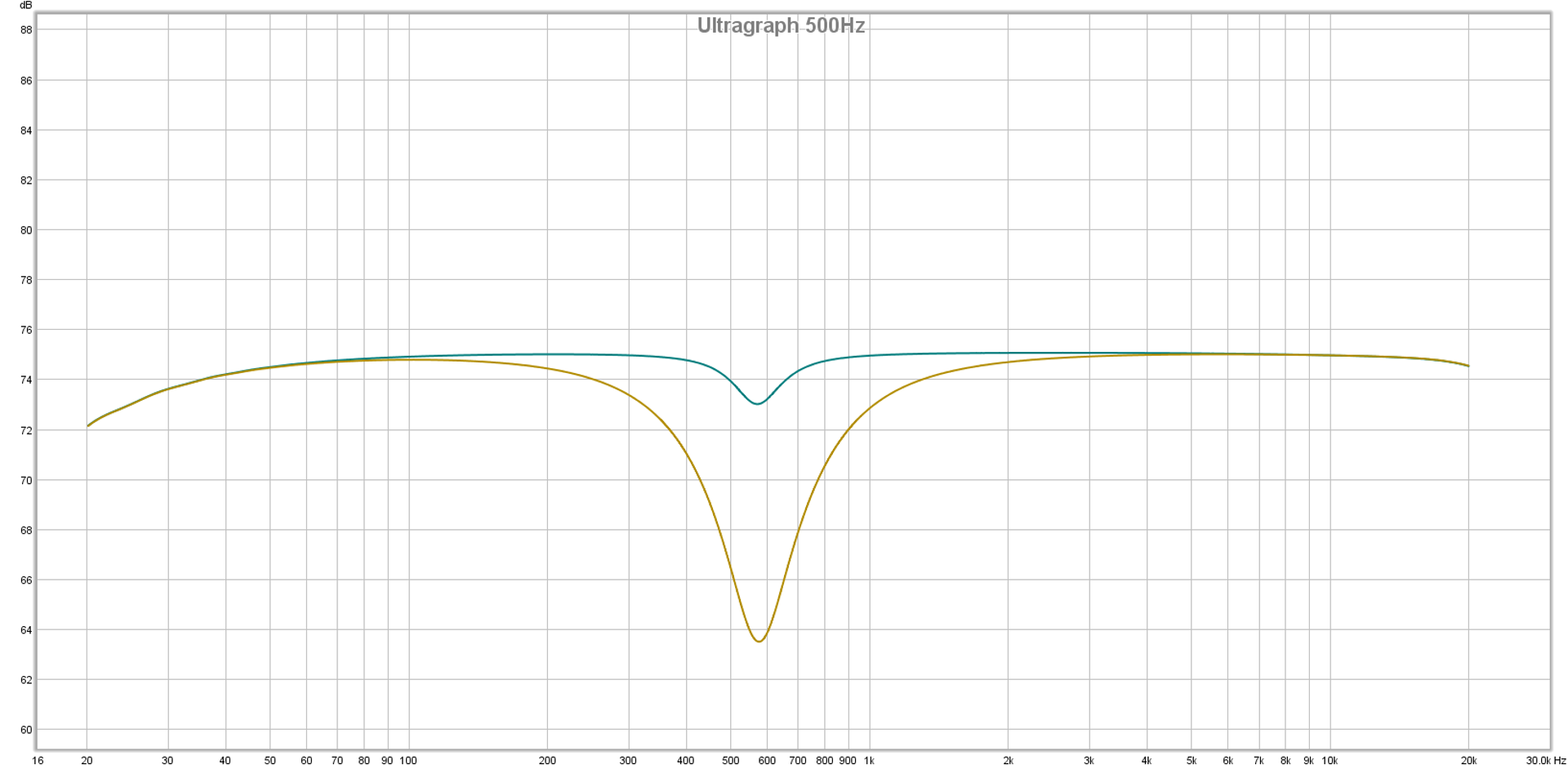

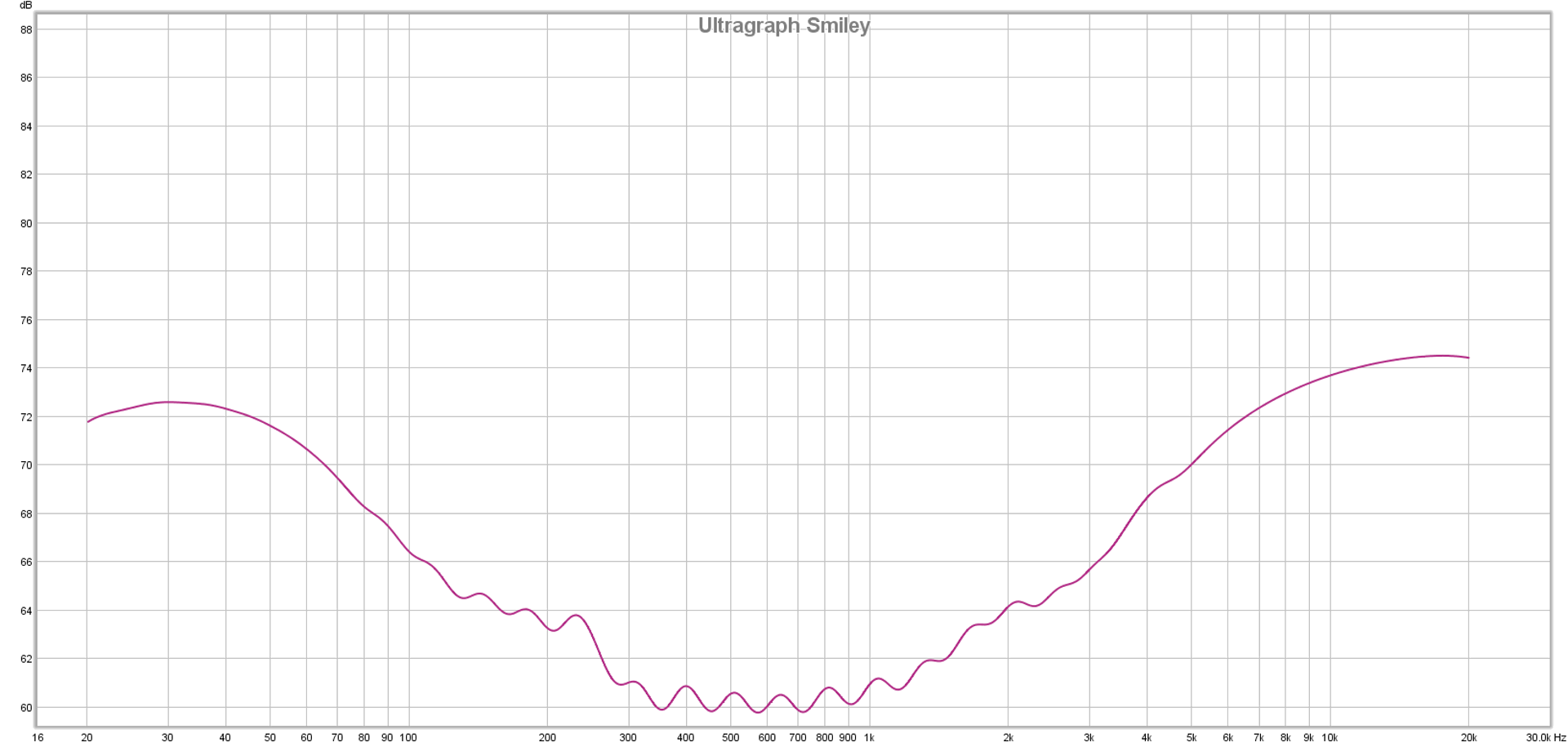

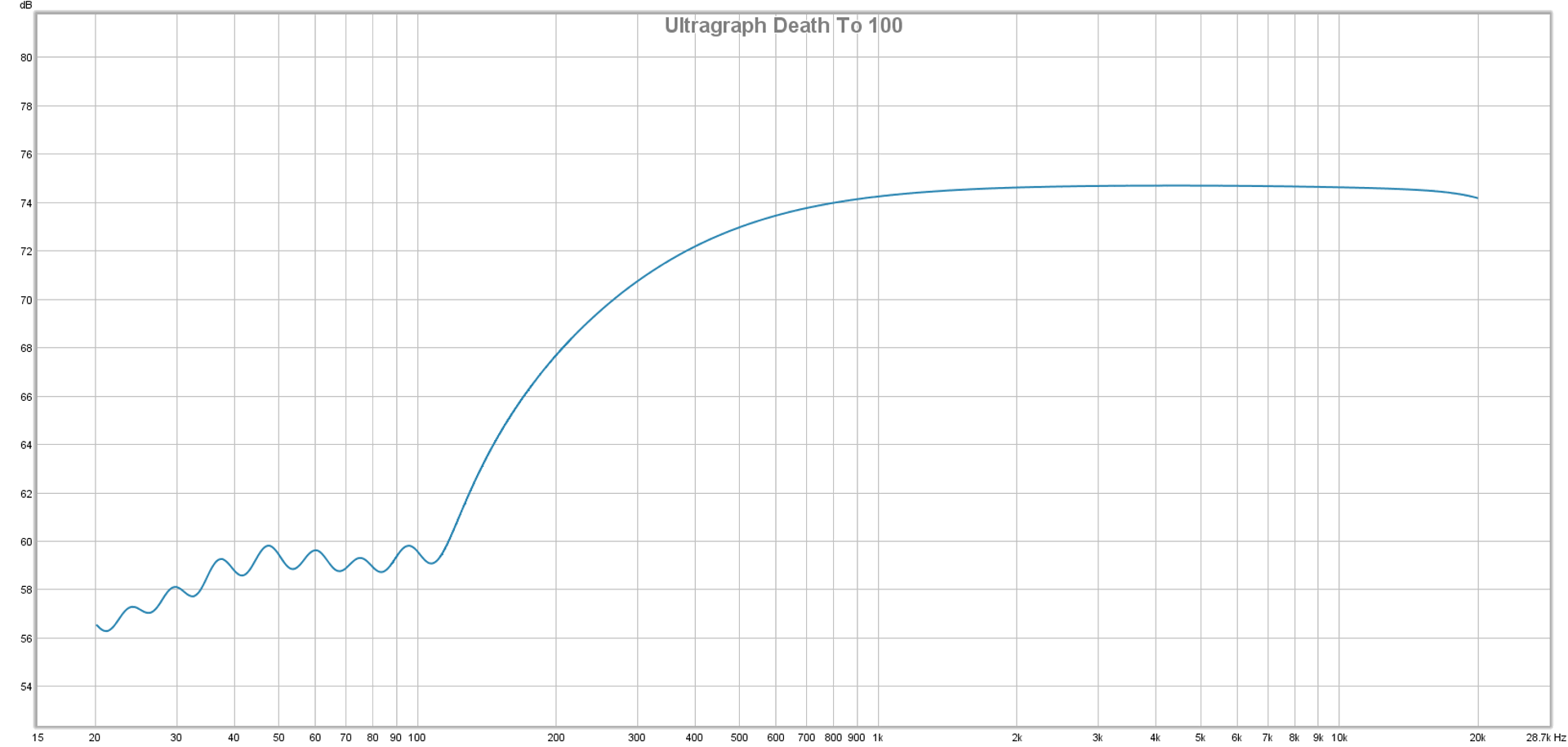

Equalization can be effective with many feedback situations, due to loop gain commonly being notably NOT equal at all frequencies. In almost any situation that you will encounter in real-life, one frequency will end up having the highest loop gain at any particular moment. That frequency, then, will be the one that “rings.”

The utility of EQ is that you can reduce a system’s electronic gain in a selected bandwidth. Preamp levels, fader levels, and send levels are all full-bandwidth controls – but if only a small part of the audible spectrum is responsible for your troubles, it’s much better to address that problem specifically. Equalizers offering smaller bandwidths allow you to make cuts in problem areas without wrecking everything else. At the same time, very narrow filters can be hard to place effectively, and a change in phase over time can push a feedback frequency out of the filter’s effective area.

EQ as a feedback management device – like everything else – is an exercise in tradeoffs. You might be able to pull off some real “magic” in terms of system stability at high gain, but the mics might sound terrible afterwards. You can easily end up applying so many filters that reducing a full-bandwidth control’s level would do basically the same thing.

In general, doing as much as possible to tame your feedback dragon before the EQ gets involved is a very good idea. You can then use equalization to tamp down a couple of problem spots, and be ready to go.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.