Let’s measure some boxes!

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.Over time, I’ve become more and more interested in how different products compare to each other in an objective sense. This is one reason why I put together the The Great, Quantitative, Live-Mic Shootout. What I’m especially intrigued about right now is loudspeakers – especially those that come packaged with their own internal amplification and DSP. Being able to quantify value for money in regards to these units seems like a nifty exercise, especially as there seems to be a significant amount of performance available at relatively low cost.

Over time, I’ve used a variety of powered loudspeakers in my work, and I have on hand a few different models. That’s why I tested what I tested – they were conveniently within reach!

Testing Notes

1) The measurement mic and loudspeaker under test were set up to mimic a situation where the listener was using the loudspeaker as a stage monitor.

2) A 1-second, looping, logarithmic sweep was used to determine the drive level where the loudspeaker’s electronics reached maximum output (meaning that a peak/ limit/ clip indicator clearly illuminated for roughly half a second).

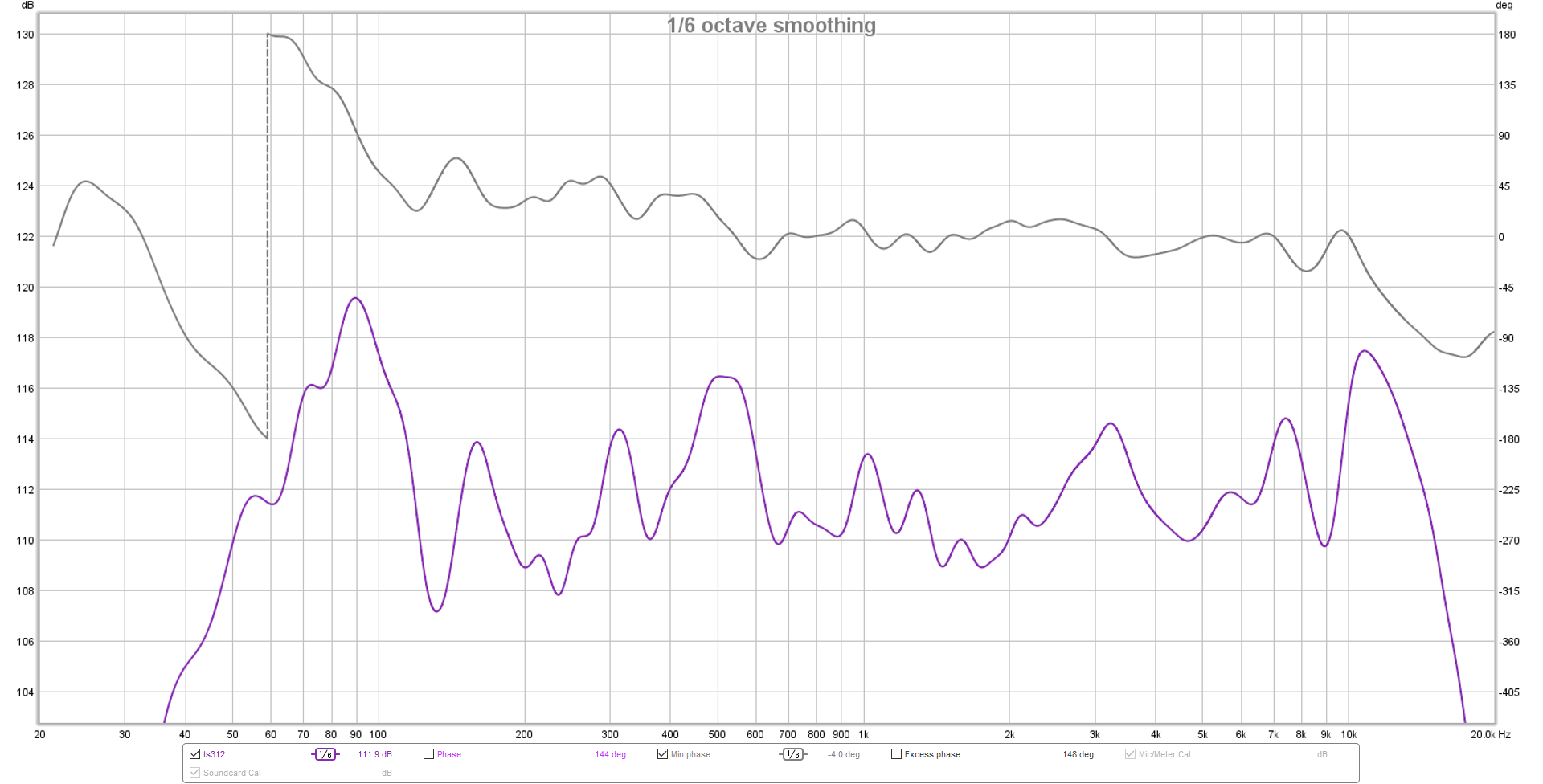

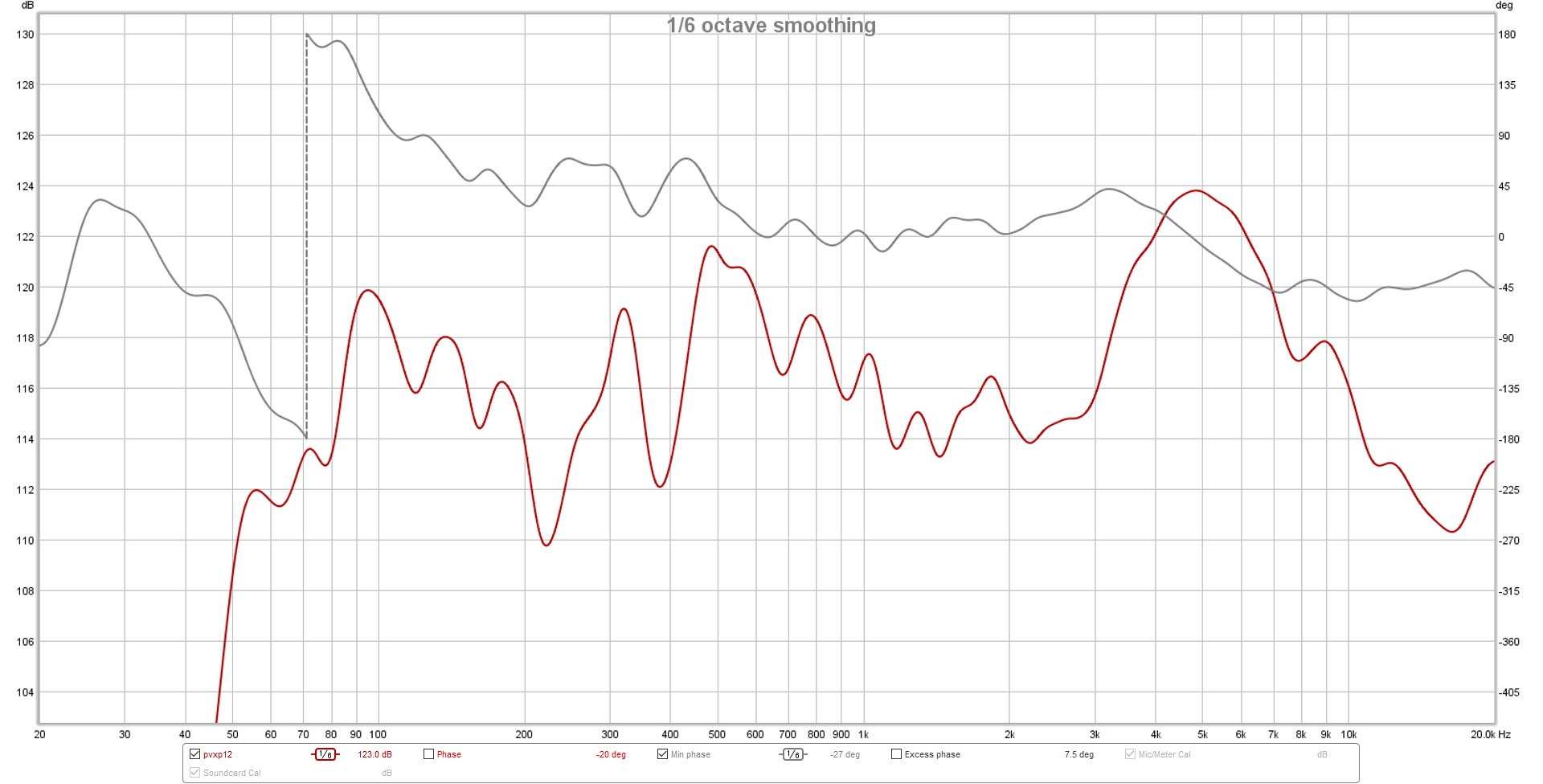

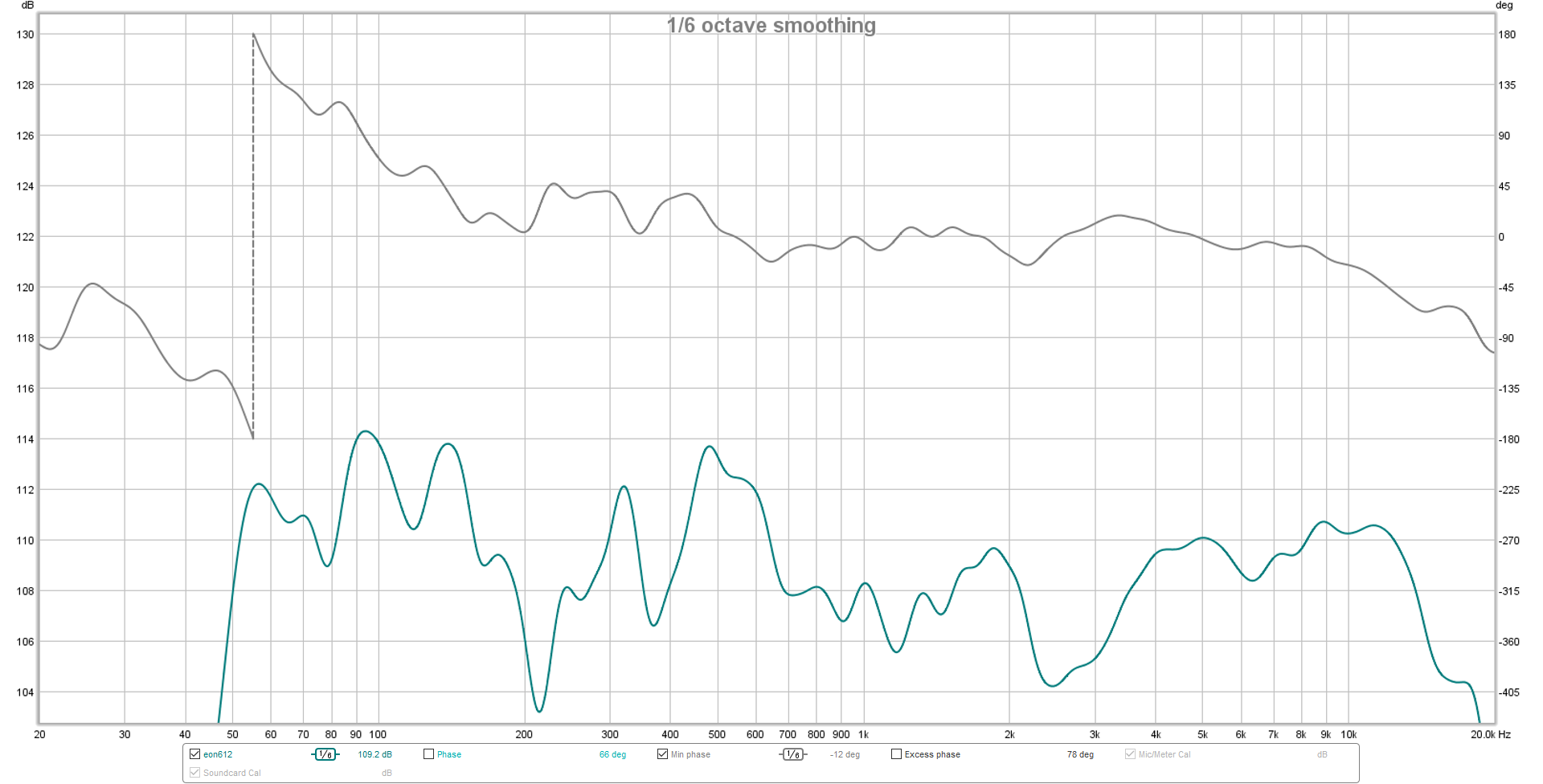

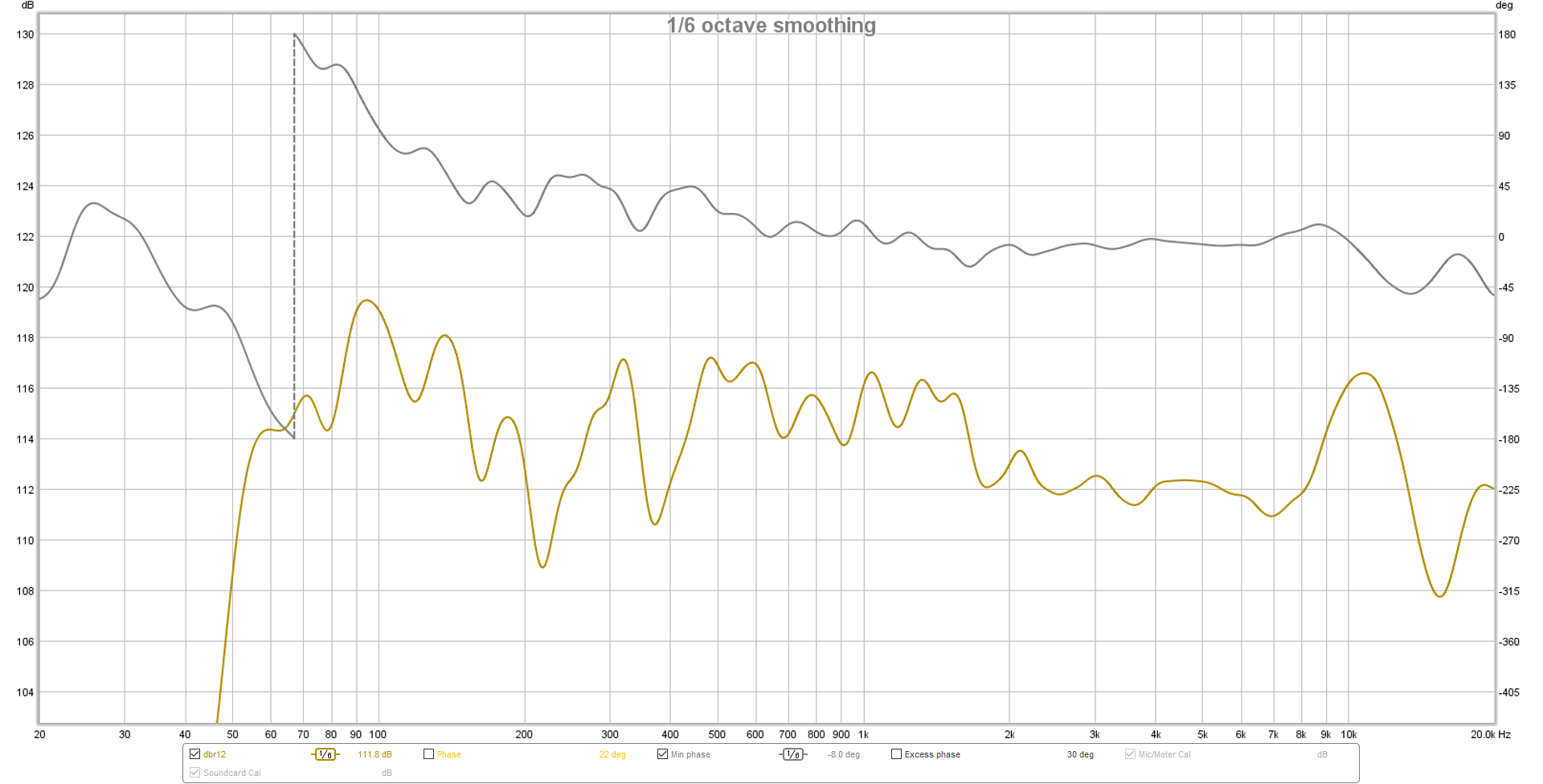

3) Measurements underwent 1/6th octave smoothing for the sake of readability.

4) These comparisons are mostly concerned with a “music-critical band,” which I define as the range from 75 Hz to 10,000 Hz. This definition is based on the idea that the information required for both creating music live and enjoying reproduced sound is mostly contained within that passband.

5) “Volume” is the number of cubic inches contained within a rectangular prism just large enough to enclose the loudspeaker. (In other words, how big of a box just fits around the loudspeaker.)

6) “Flatness Deviation” is the difference in SPL between the lowest recorded level and highest recorded level in the music-critical band. A lower flatness deviation number indicates greater accuracy.

6) Similarly to #5, “Phase Flatness Deviation” is the difference between the highest phase and lowest phase degrees recorded in the music-critical band. (The phase trace is a generated, minimum-phase graph).

8) Distortion is the measured THD % at 1 kHz.

9) When available, in-box processing was set to be as minimal as possible (i.e., flat EQ).