There are plenty of controls I didn’t like, though…

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

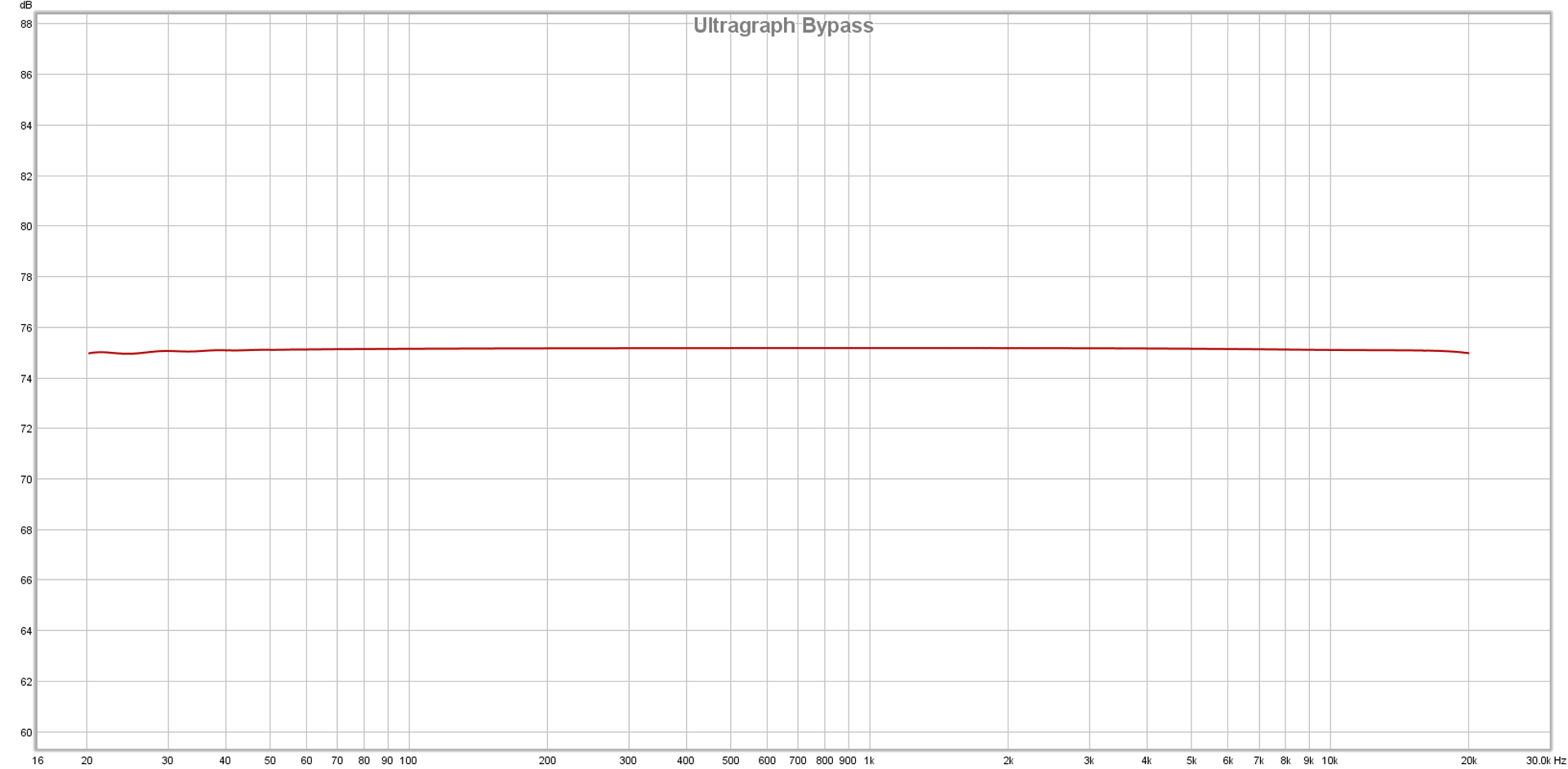

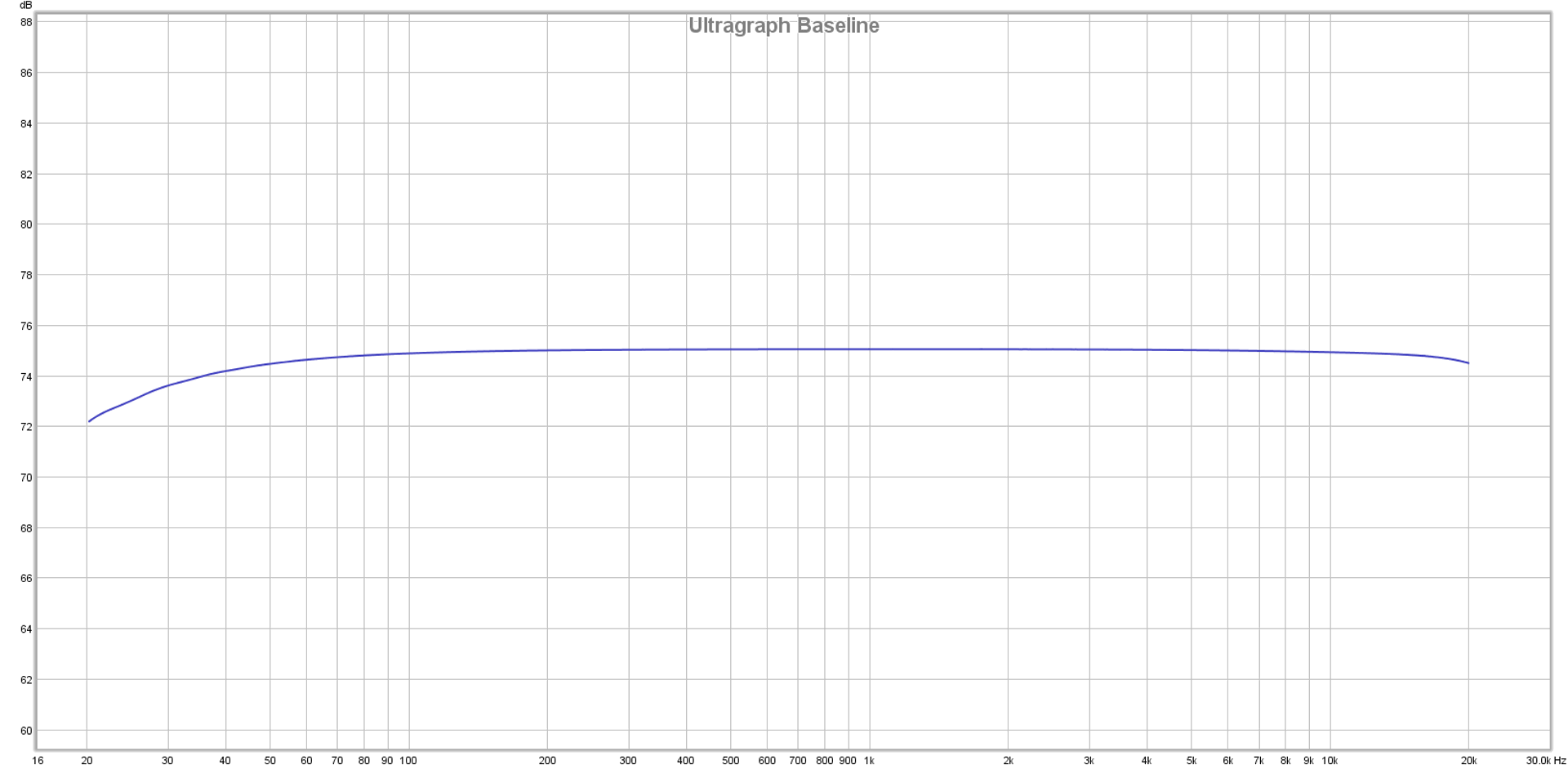

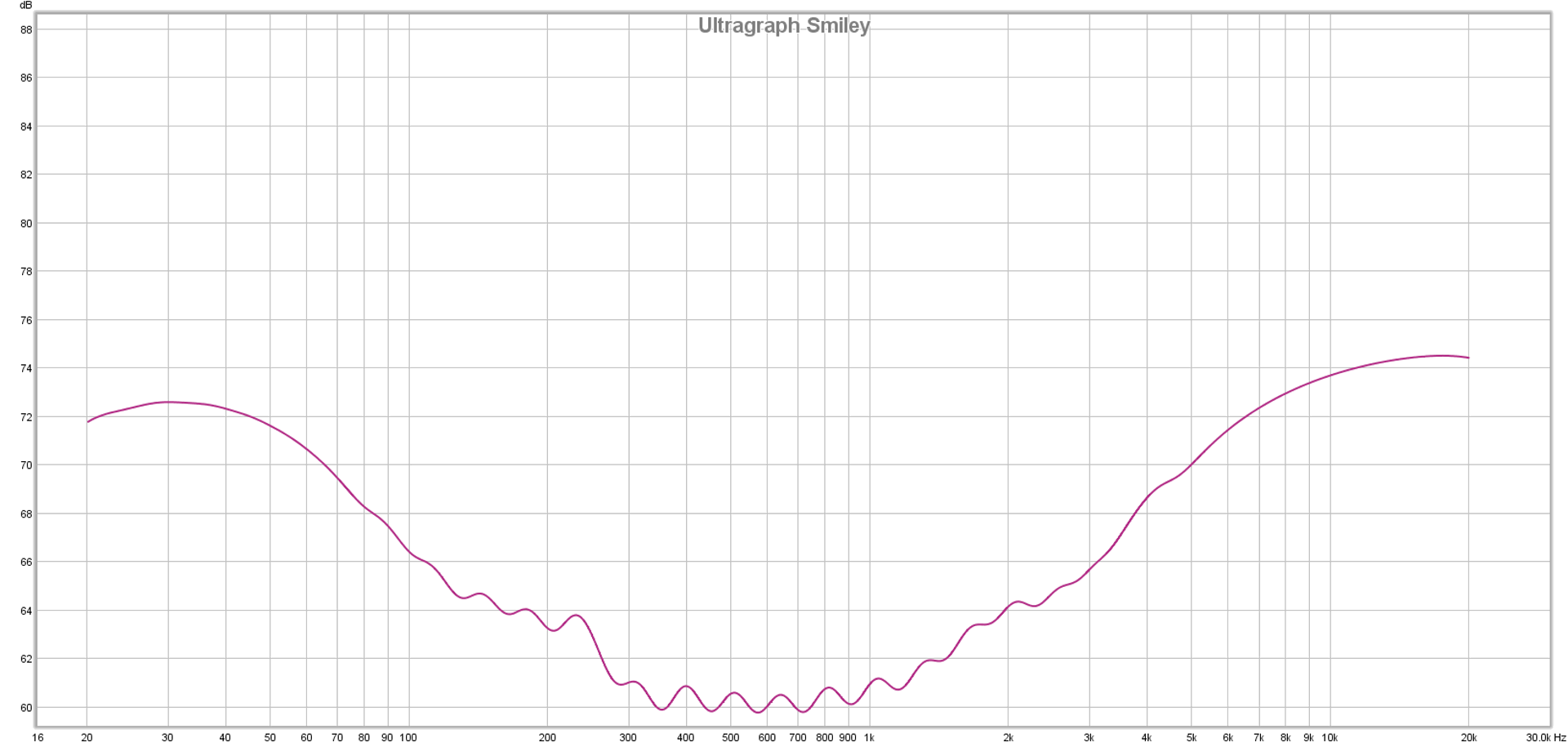

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

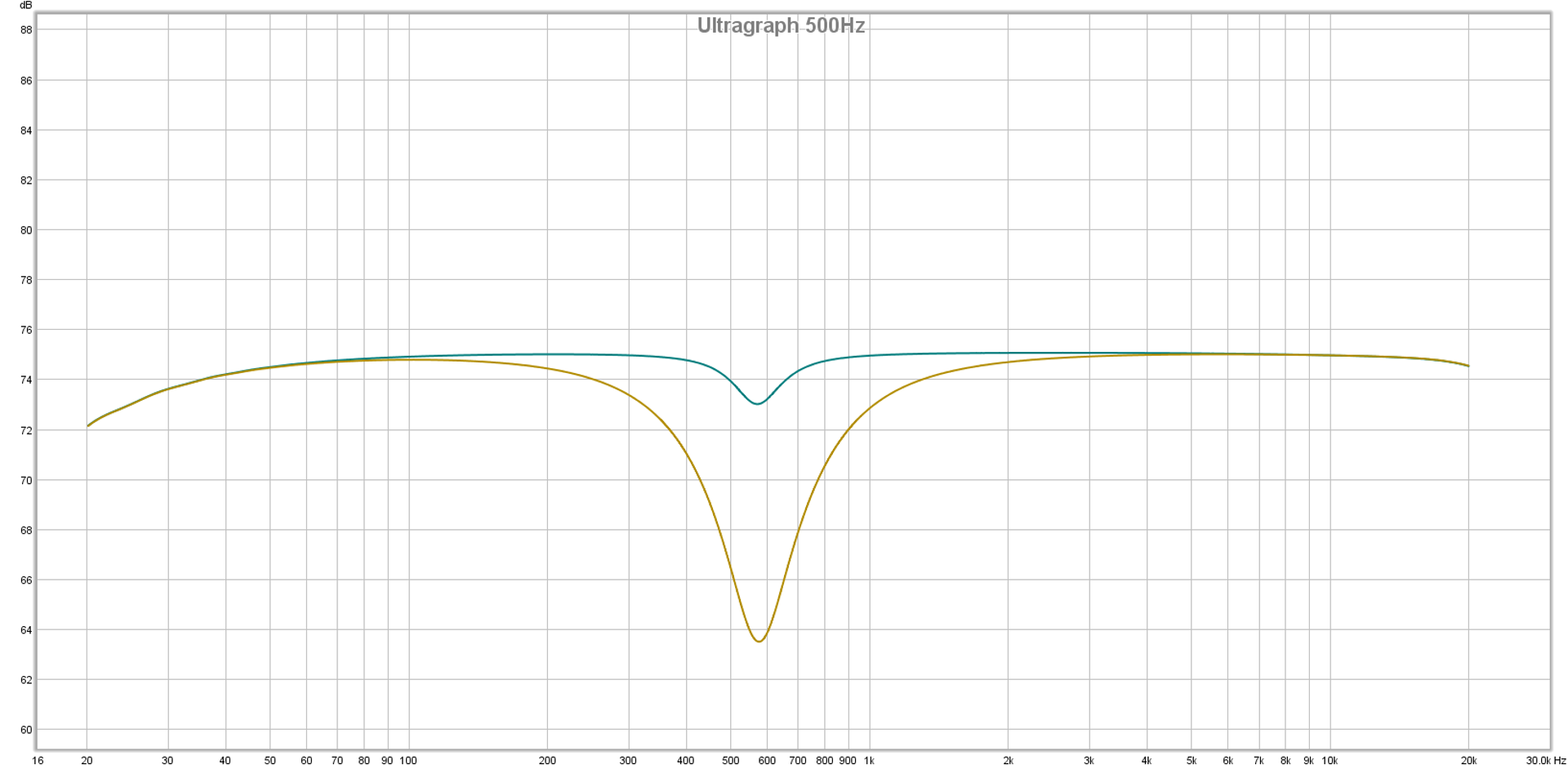

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.I’ve talked about this before, but it’s on my mind again.

As of today, I’ve clocked nearly 24 years of involvement in live audio. In that time, I’ve had hands-on time with mixers by Ramsa, Peavey, JBL, Behringer, Soundcraft, A&H, Yamaha, Tascam, Avid, Solid State Logic, Amek, Neve, and…ah…and…at least one more that I can’t remember for some reason. Some of them were worth tens of dollars. Some of them were worth tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars. Some of them were analog. Some of them were digital.

I never once had a problem with how any of them “sounded.” I have never been in a situation with a real band in a real room and said to myself, “Gee, this would sound so much better if I had a [consoleName].”

I’ve disliked control layouts, though. I’ve wondered why the big, fancy, industry darling didn’t have conveniences that a console costing less than 1/10th of it had. I’ve encountered fixed-width midrange EQs that were metaphorical equivalents to carving a turkey with a tractor-trailer hauling 17 tons of other, very alive and extremely enraged turkeys bent on world domination HUMANS, YOUR HUBRIS WILL END YOU! WE ARE COMING! GOBBLEGOBBLEGOBBLE!

Sorry, what were we talking about?

Yes, I’ve encountered some consoles that sounded terrible because an internal connection had worked loose, or a button contact was grunged up. When everything was working, though, all the mixers in my experience have passed audio just as well as anything else. Then, that audio hit outboard processing, loudspeakers, and acoustical environments, and all bets were off. There are plenty of people who might ask, “What console do we need to buy to make this place sound better?” and I might answer:

“Forget the console. You need a bulldozer, municipal construction permits, an architecture firm, and a bunch of money to build a room that’s actually suited to live music.”

I can not recall a single instance in my life where I disliked the sound of a show and could confidently attribute that dislike to a deficiency in the basic audio-handling properties of a mixing desk. Operators, input/ output transduction, and environmental factors are sonic influencers possessing orders of magnitude more significance.