This article is the “closing vertex” of my semi-intentional “Gain, Stability, And The Best Holistic Show” trilogy.

I’m here to agree and disagree with Alan Parsons. Yes, that Parsons. The guy who engineered “Dark Side of the Moon.” A studio engineer with a career that most of us daydream about. An audio craftsperson who truly lives up to the title in the best way.

I am NOT here to trash the guy.

What I am here to do is to talk about a disagreement I have regarding the application of a specific bit of theory. It was a bit of theory that was first presented to me by the late Tim Hollinger (whom I greatly miss). Tim told me about an article he read where Alan Parsons explained why he (Parsons) mics guitar cabinets from a distance. Part of Parsons’ rationale is that nobody listens to guitar amps with their ear right up against the speaker, and also that guitar players are so loud that he doesn’t have a bleed problem.

I don’t know if the Premier Guitar article I found is the same one that Tim read, but it might be. You can read it here. The pertinent section is below the black and white picture of Parsons working in the studio.

Alan Parsons Is Academically Right

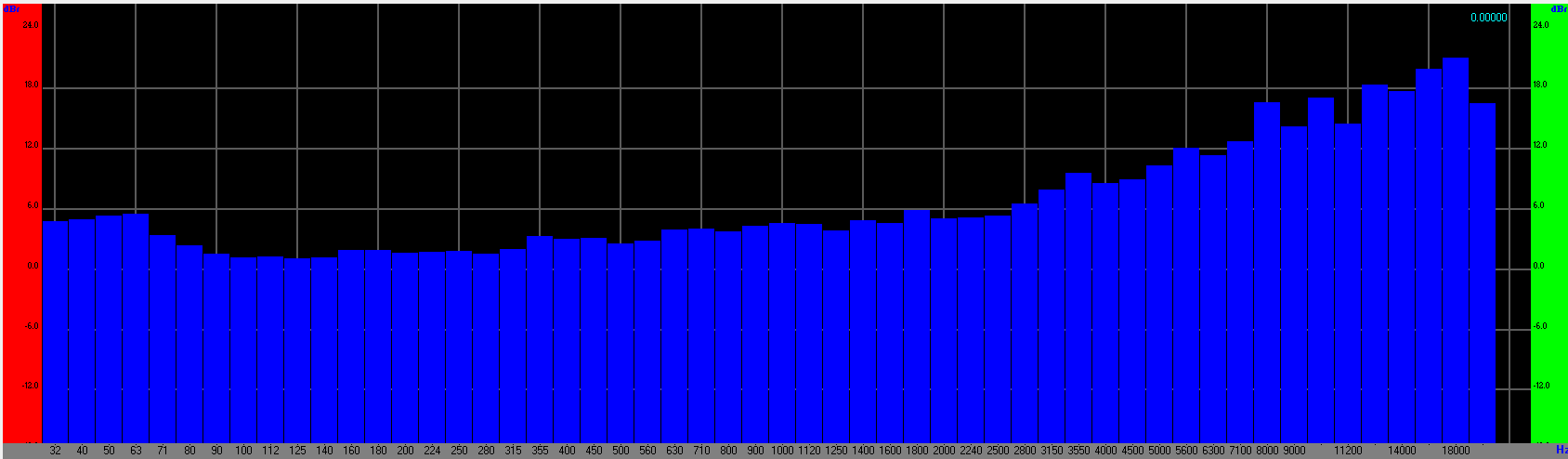

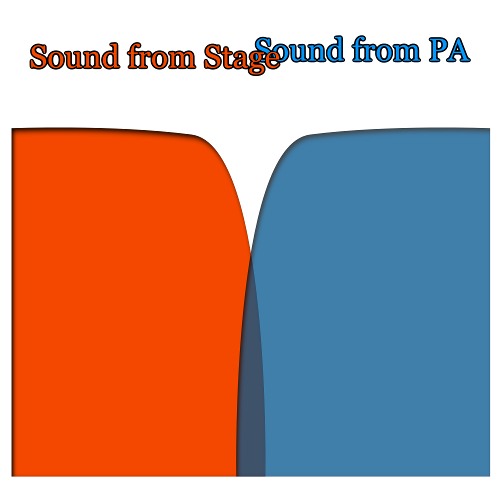

I don’t know of any guitar player who listens to their rig with an ear pressed up to the grill cloth. I can also tell you that, in lots of small-venue cases, a LOT of what the audience hears is the entirety of the guitar cab. A close-miced version of that sound might also be present in the PA, but it’s not the totality of the acoustical “solution.”

Also, yes, there are plenty of guitar players who run their rigs “hot.” Move a mic 18 inches from the cab when working with a player like that, and bleed might not be too problematic in a recording context, even if everybody’s in the same (largish) room. Solo the channel into a pair of headphones, and you’ll probably go, “Yup, there’s plenty of guitar in that mic.”

There’s not much to say about the correctness of Alan Parsons’ factual assertions, because they’re…well…correct.

The Problem Is Application

So, if Parsons is accurate about his rationale, how can there be a disagreement?

It’s pretty easy actually, and it comes from a statement that Parsons makes in the article I linked above: “Live sound engineers just don’t seem to get it.”

Parsons is correct about that too. Really! Concert-sound humans, in a live context, DON’T “get” studio recording applications. The disciplines are different. In precisely the same way, I can say that studio engineers don’t “get” live sound applications in the live context. This all comes back to what I’ve said in earlier articles: The live-audio craftsperson’s job is to produce the best holistic show possible at the lowest practicable gain. The studio craftsperson’s job is to capture the best possible sound for later reproduction. These goals are not always fully compatible, especially in a small-venue context.

(And before you write me hate-mail, it’s entirely possible for an audio human to become competent in both studio and live disciplines. What I’m getting at here is that each discipline ultimately has separate priorities.)

Obviously, there are some specifics that need addressing here. The divergent needs of the studio and live disciplines take different roads at a number of junctions.

I Don’t Want To Mic The Room, Thanks

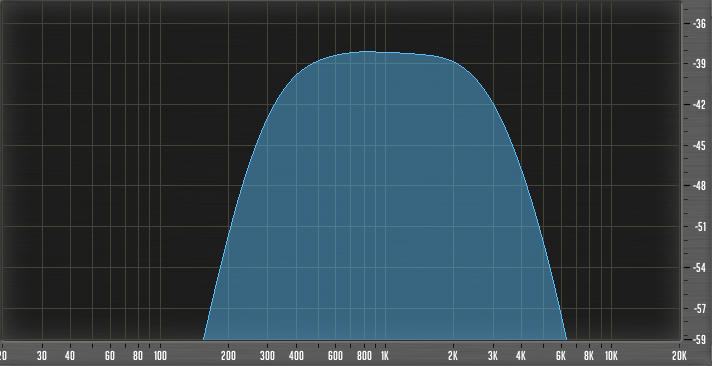

In the studio, getting some great “ambience” is a prized piece of both the recording process and the choosing of a recording space. The very best studios have rooms that enhance the sound of the various sources put into them. Grabbing a bit of this along with the correct dose of the “direct” sound from a source is something to be desired. It enhances the playback of that recording, which takes place at another time in another room – or is delivered directly to a person’s ear canal, in the case of headphones.

But this is not at ALL what I want as a live-audio practitioner.

For me, more often than not, a really beautiful-sounding room is an unlikely thing to encounter. There are such things as venues with tremendously desirable acoustics, but most of the time, a venue is primarily built to satisfy the logistics of getting lots of people into one space in whatever way is practical. In general, I regard any environmental acoustics to be a hostile element. Even a relatively nice room is troublesome, because it still causes me to have to deal with multiple, indirect arrivals which smear and garble the overall sound of the show. Unlike in a recording context, I am guaranteed to hear the ambience of the room.

Lots of it.

Too much, in fact.

I do NOT want any more of it to get captured and shot out of the PA, thanks very much. I don’t need my problems to be compounded. In the very often occurring case that I need to forge a total solution by combining room sound with PA sound, I want the sound in the PA to NOT reinforce the “room tone” at all. I’ve already got the sound of the room. What I need is something else.

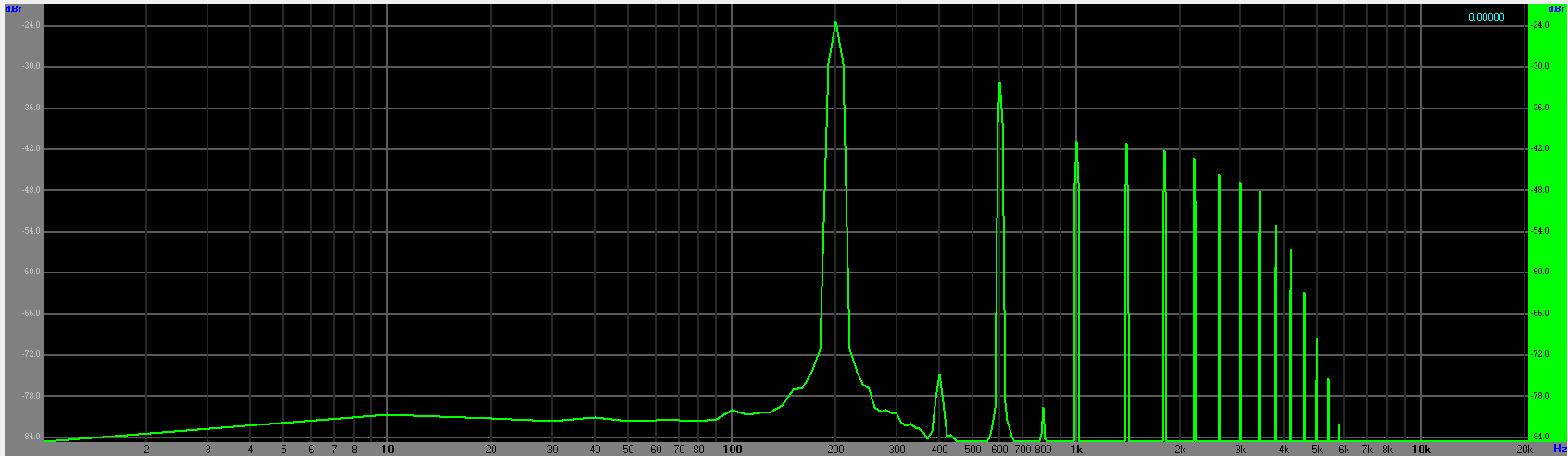

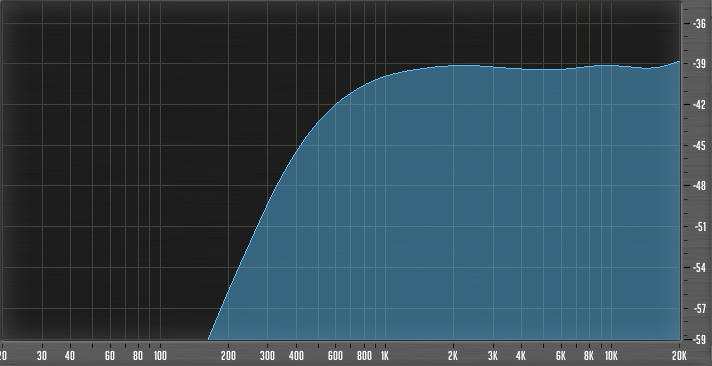

Close micing prevents my transducers from capturing “the room” and passing that signal on to the rest of the system.

Specificity Is My Friend

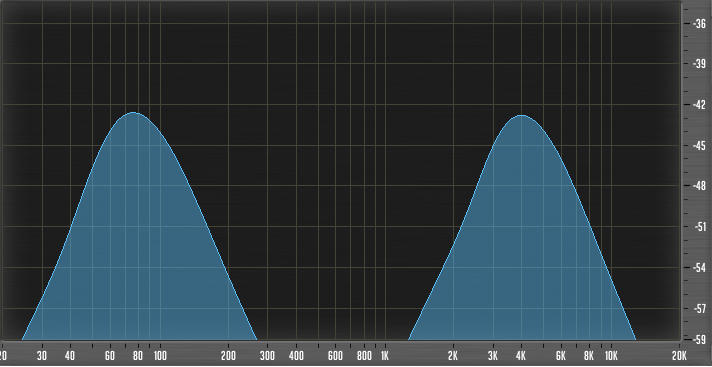

For a recording engineer, a bit of “bleed” from the drumkit (and everything else) is not necessarily a bad thing. For me, though, it’s counterproductive. If I need more guitar because the drums are too strong, I do NOT want any more drums at ALL. I want guitar only, or vice versa.

Especially in small-venue live-sound, you tend to have sources that are very close together (often much closer than they would be in a nice studio), and loud wedges instead of headphones. On a large stage, this problem is mitigated somewhat, but that’s not what I tend to run into. Also, in a studio, it’s very possible to arrange the band such that directional microphone nulls help to minimize the effects of bleed. Small venues and expectations of what a band’s setup is “supposed” to look like often get in the way of doing this live.

In any case, live show bleed tends to be much more severe than what a studio engineer might encounter. This compounds the “I need more this, not that” problem above.

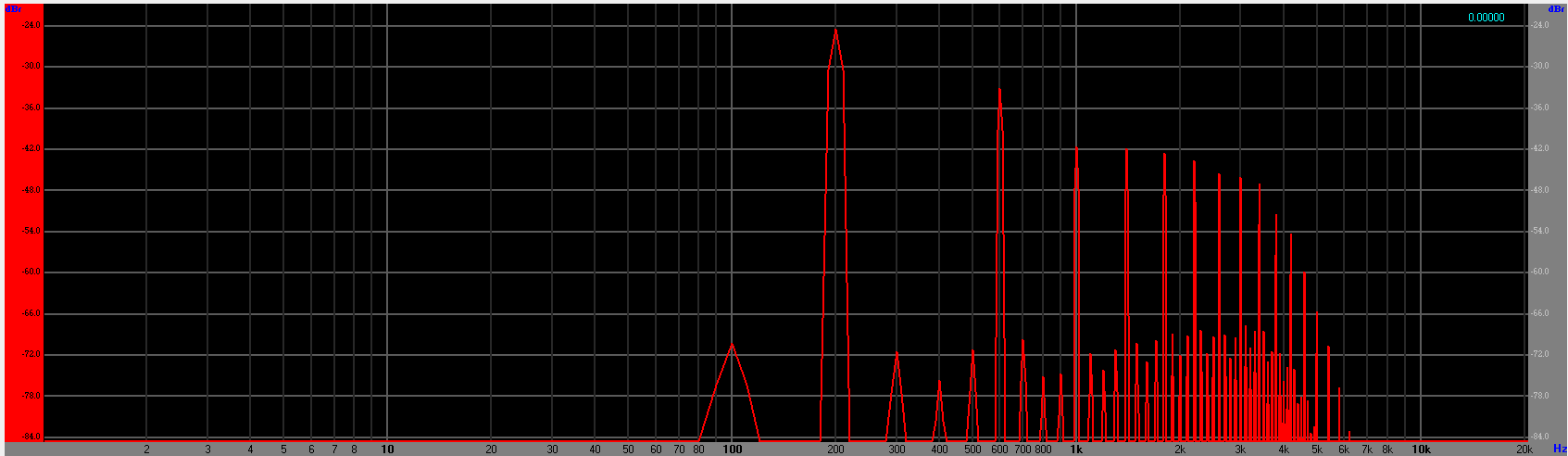

As an example, I recently worked with a band where the drummer specifically asked for his kit to be miced with overheads. I happily obliged, because I wanted to be accommodating. (Part of producing the best holistic show is to have comfortable, happy musicians.) At soundcheck, I took a quick guess at where the overheads should be. I wouldn’t say that we could really hear them, but hey, we had a decent total solution in the room pretty much immediately. I didn’t really think about the overheads much. About halfway through the show, though, I got curious. I soloed the overheads into my headphones.

In order to get the drum monitors where he wanted them, we had so much guitar and bass coming through that they almost swamped the drums in the overheads.(!) The overheads were basically useless as drum reinforcement, because they would pretty much end up reinforcing everything ELSE.

If a mic is going to be useful for live sound reinforcement, specificity is critical. Pulling a mic away from a source is counterproductive to that discrimination, so I prefer not to do it.

Lowest Practicable Gain

In general, higher gain is not a problem for studio folks. Yes, it might result in greater noise, and it can also reduce electronic component bandwidth, but it’s really a very small issue in the grand scheme of things.

In live audio, higher gain is an enemy. Because microphones encounter sounds that they have already picked up and passed along to the rest of the PA, they exist in a feedback loop. As the gain applied to the mic goes up, the more likely it is that the feedback loop will destabilize and ring. If I can have lower gain, I will take it, even if that means a slightly unnatural sound.

Now, you might not think that feedback would be a problem with a source as loud as a guitar amp can be, but you also may not have been in situations that I’ve encountered. I have been in situations where players, even with reasonably loud amplifiers, have asked for a metric ton of level from the monitors. Yes, I’ve gotten feedback from mics on guitar amps. (And yes, we should have just turned up the amplifiers in the first place, but these situations developed in the middle of fluid shows where stopping to talk wasn’t really an option. Look, it’s complicated.)

Even if the chance of feedback is unlikely – as it usually is with louder sources – I do NOT want to do anything that causes me to have to run a signal path at higher gain. Close micing increases the apparent sound pressure level at the transducer capsule, which allows me to run at lower gain for a given signal strength.

The overall point of this is pretty simple: The desires of recording techs and the needs of live-sound humans don’t always intersect in a pretty way. When I disagree with Alan Parsons, it’s not because he doesn’t have his facts straight, and it’s not that I’m somehow more knowledgeable than he is. I disagree because applying his area of discipline to mine simply isn’t appropriate in the specific context of his comments, and the specific live-show contexts I tend to encounter.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.