On the heels of my last article, it came to may attention that some folks were – shall we say – perplexed about my whole “double hung” PA deployment. As can be the case, I didn’t really go into any nuance about why I did it, or what I expected to get out of it. This lead some folks to feel that it was a really bizarre way to go about things, especially when a simpler solution might have been a better option.

The observations I became aware of are appropriate and astute, so I think it’s worth talking about them.

Why Do It At All?

First, we can start with that logistics thing again.

When I put my current system together, I had to consider what I was wanting to do. My desire was to have a compact, modular, and flexible rig that could “degrade gracefully” in the event of a problem. I also had no desire to compete with the varsity-level concert systems around town. To do so would have required an enormous investment in both gear and transport, one that I was unwilling (and unable) to make.

What I’ve ended up with, then, is a number of smaller boxes. If I need more raw output, I can arrange them so that they’re all hitting the same general area. I also have the option of deploying for a much wider area, but with reduced total output capability. I wouldn’t have that same set of options with a small number of larger, louder enclosures.

That’s the basic force behind why I have the rig that I have. Next come the more direct and immediate issues.

The first thing is just a practical consideration: Because my transport vehicle isn’t particularly large, I don’t really have the necessary packing options required to “leave gear on the truck.” If I’m getting the rig out, I might as well get all of it out. This leads to a situation where I figure that I might as well find a way to deploy everything all the time. The gear is meant to make noise, not sit around. “Double hung” lets me do that in a way that makes theoretical sense (I’ll say more on why in a bit).

The second reason is less practical. I have a bit of a penchant for the unconventional and off-the-wall. I sometimes enjoy experiments for the sake of doing them, and running a double hung system is just that kind of thing. I like doing it to find out what it’s like to do it.

Running double hung is NOT, by any means, more practical than other deployments. Especially if you’re new to this whole noise-louderization job, going with this setup is NOT some sort of magical band-aid that is going to fix your sound problems. Also, if you’re getting good results with a much simpler way of doing things, going to the extra trouble very well may not be worth it.

At the same time, though, the reality of making this kind of deployment happen is not really all that complicated. You can do it very easily by connecting one pair to the left side of your main mix, and the other pair to the right side. Then, you just pan to one side or the other as you desire.

System Output And Response

Up above, I mentioned that running my system as a double hung made sense in terms of audio theory. Here’s the explanation as to why. It’s a bit involved, but stick with me.

I haven’t actually measured the maximum output of my FOH mid-highs, but Turbosound claims that they’ll each make a 128 dB SPL peak. I’m assuming that’s at 1 meter, and an instantaneous value. As such, my best guess at their maximum continuous performance, run hard into their limiters, would be 118 dB SPL at 1 meter.

If I run them all together as one large rig, most people will probably NOT hear the various boxes sum coherently. So, the incoherent SPL addition formula is what’s necessary: 10 Log10[10^(dB SPL/ 10) + 10^(dB SPL/ 10)…]. What I put into Wolfram Alpha is 10 Log10[10^11.8 + 10^11.8 + 10^11.8 + 10^11.8].

What I get out is a theoretical, total continuous system output of 124 dB SPL at 1 meter, ignoring any contribution from the subwoofers.

At this point, you would be quite right to say that I can supposedly get to that number in one of two ways. The first, simple way, is to just put everything into all four boxes. The second, not simple way is to put some things in some boxes and not in others. Either way, the total summed sound pressure should be basically the same. The math doesn’t care about the per-box content. So, why not just do it simply?

Because there’s more to life than just simply getting to the maximum system output level.

By necessity of there being physical space required for the speakers to occupy, the outer pair of enclosures simply can’t create a signal that arrives at precisely the same moment as the signal from the inner pair, as far as the majority of the audience can perceive. Placed close together, the path-length differential between an inner box and an outer box is about 0.0762 meters, or 3 inches.

That doesn’t seem so bad. The speed of sound is about 343 meters/ second in air, so 0.0762 meters is 0.22 ms of delay. That also doesn’t seem so bad…

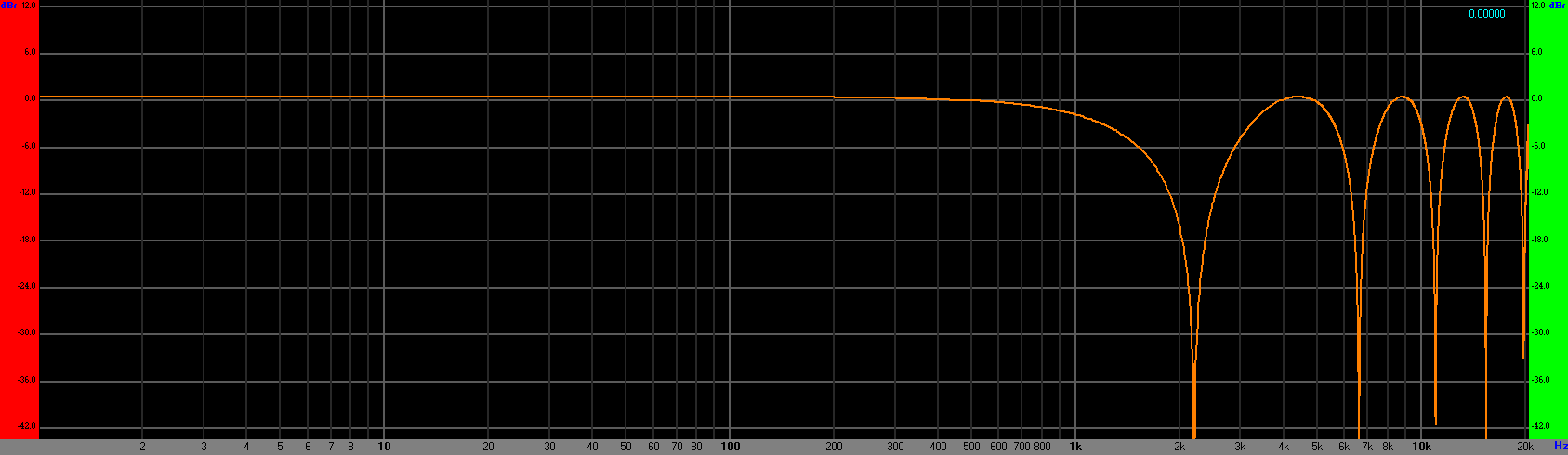

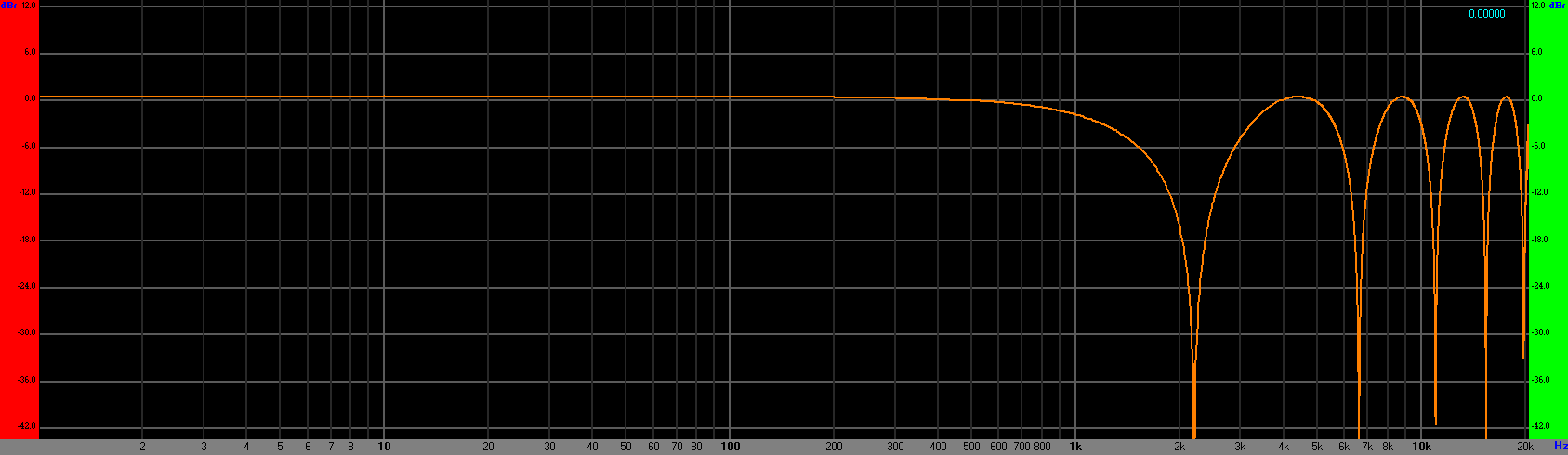

…until you realize that 0.22 ms is the 1/2 cycle time of 2272 Hz. With the outer boxes being 1/2 cycle late, 2272 Hz would null (as would other frequencies with the same phase relationship). If everything started as measuring perfectly flat, introducing that timing difference into a rig with multiple boxes producing the same material would result in this transfer function:

Of course, everything does NOT start out as being perfectly flat, so that craziness is added onto whatever other craziness is already occurring. For most of the audience, plenty of phase weirdness is going on from any PA deployed as two, spaced “stacks” anyway. To put it succinctly, running everything everywhere results in even more giant holes being dug into the critical-for-intelligibility range than were there before.

Running double hung, where the different pairs of boxes produce different sounds, prevents the above problem from happening.

So, when I said that I was running double hung for “clarity,” I was not doing it to fix an existing clarity problem. I was preventing a clarity problem from manifesting itself.

Running absolutely everything into every mid-high, and then having all those mid-highs combine is a simple way to make a system’s mid-highs louder. It’s also a recipe for all kinds of weird phase interactions. These interactions can be used intelligently (in an honest-to-goodness line-array, for instance), but for most of us, they actually make life more difficult. Louder is not necessarily better.

More On Output – Enough Rig For The Gig?

For some folks reading my previous installment, there was real concern that I hadn’t brought enough PA. They took a gander at the compactness of the rig, and said, “There’s no way that’s going to get big-time sound throughout that entire park.”

The people with that concern are entirely correct.

But “rock and roll level everywhere” was not at all what I was trying to do.

The Raw Numbers

What I’ve found is that many people do NOT actually want everything to be “rock and roll” loud over every square inch of an event area. What a good number of events actually want is a comfortable volume up close, with an ability to get away from the noise for the folks who aren’t 100% interested. With this being the case, investing in a system that can be clearly heard at a distance of one mile really isn’t worthwhile for me. (Like I said, I’m not trying to compete with a varsity-level sound company.)

Instead, what I do is to deploy a rig that’s in close proximity to the folks who do want to listen, while less interested people are at a distance. Because the folks who want more volume are closer to the PA, the PA doesn’t have to have crushing output overall. For me, the 110 dB SPL neighborhood is plenty loud, and I can do that for the folks nearby – by virtue of them being nearby.

Big systems that have to cover large areas often have the opposite situation to deal with: The distance differential between the front row and the back row can actually be smaller, although the front row is farther away from the stacks in an absolute sense. With my rig, the people up close are probably about three meters from the PA. The folks far away (who, again, aren’t really interested) might be 50 meters away. That’s more than a 16-fold difference. At a bigger show, there might be a barricade that’s 10 meters from the PA, with the main audience extending out to 100 meters. That’s a much bigger potential audience, but the difference in path lengths to the PA is only 10-fold.

Assuming that the apparent level of the show drops 6 dB for every doubling of distance, my small show loses about 24 decibels from the front row to the folks milling around at 50 meters. The big show, on the other hand, loses about 20 dB. (But they have to “start” much louder.)

That is, where the rubber hits the road is how much output each rig needs at 1 meter. At the big show, they might want to put 120 dB SPL into the front seats. To do that, the level at 1 meter has to be 140 dB. That takes a big, powerful PA. The folks in the back are getting 100 dB, assuming that delays aren’t coming into the picture.

For me to do a show that’s 110 dB for the front row, my PA has to produce about 119 dB at 1 meter. That’s right about what I would expect my compact setup to be able to do, with a small sliver of headroom. At 50 meters, my show has decayed to a still audible (but not “rock show loud”) 86 dB SPL.

That’s what I can do, and I’ve decided to be happy with it – because the folks I work with are likely to be just as happy with that as I am. People don’t hire me to cover stadiums or have chest-collapsing bass. They hire me because they know I’ll do everything in my power to get a balanced mix at “just enough” volume.

The Specifics Of The Show

Ultimately, the real brass tacks are to be found in what the show actually needed.

The show did not need 110 dB SPL anywhere. It needed a PA that sounded decent at a moderate volume.

The genre was folksy, indie material. A 110 dB level would have been thoroughly inappropriate overkill. At FOH control, the show was about 80 – 90 dB, and that was plenty. There were a few times where I was concerned that I might have been a touch too loud for what was going on. In that sense, I had far more than enough PA for raw output. I could have run a single pair of boxes and been just fine, but I didn’t want to get all the speakers out of the van and not use them. As I said before, I chose “double hung” to use all my boxes, and to use them in the way that would be nicest for people’s ears.

If you’re curious about running a double hung setup, I do encourage you to experiment with it. Curiosity is what keeps this industry moving. At the same time, you shouldn’t expect it to completely knock you off your feet. If you have a good-sounding system that runs everything through one pair of mains, adding another pair just to split out some sources is unlikely to cause a cloud-parting, ligh-ray-beaming experience of religious proportions. Somewhat like aux-fed subwoofers, going double hung is a taste-dependent route to accomplishing reinforcement for a live event. For me, it solves a particular problem that is mostly logistical in nature, and it sounds decent doing it.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.