Your biases can kick your own butt.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

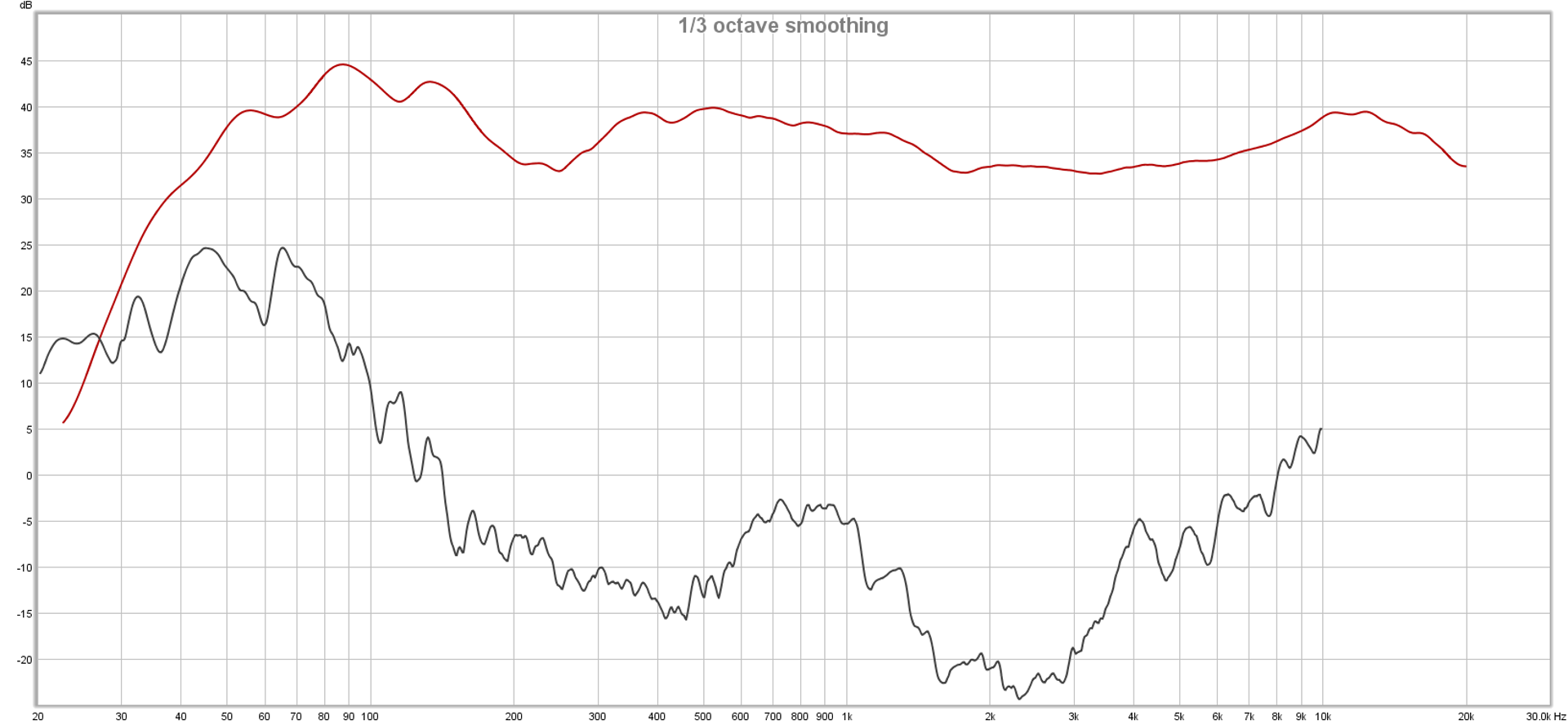

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

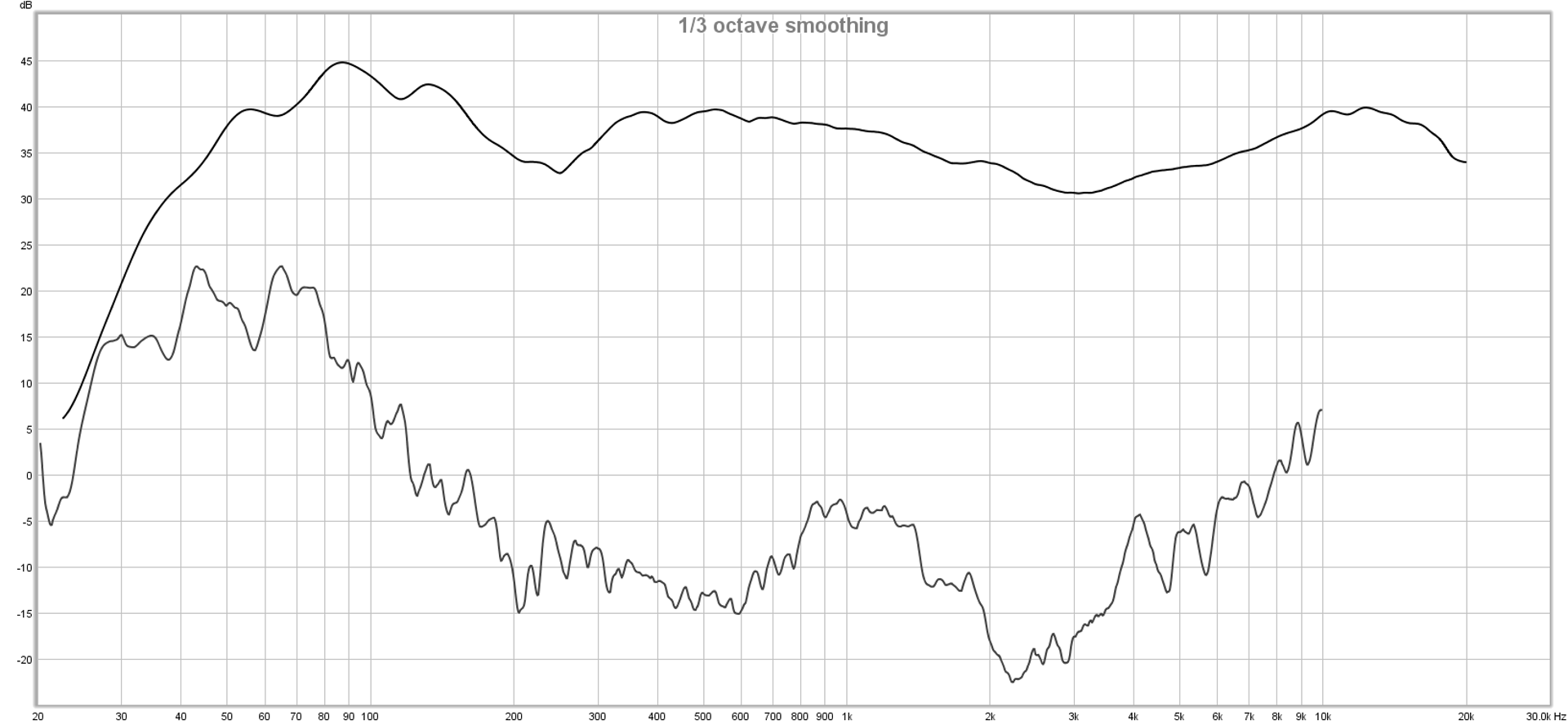

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.I am sometimes hired to go in and fix things.

Such was the case with a recent event at a small but classy amphitheater. The show promoters had brought me in because of severe problems they had encountered on the previous attempt. A year earlier, the show had been badly marred by persistent feedback issues, and there was a real (entirely founded) concern that the house crew was simply not up to the task.

“The monitors were SO LOUD,” it was said to me, and I was sure I could make things better. Firstly, I would be sure to run things at a reasonable volume – and the rest would surely be academic.

Thus, I got the gig. Then we had a site visit. At the end of the visit, I made a plan: I would take some of the realtime workload off the house FOH engineer by running monitor world. They had all the loudspeaker hardware we needed, so I’d just bring a console and a split. No problem!

The day came, we patched in, and started line checking. Everything was fine, although I felt like I had to be “on the gas” to get a reasonable amount of SPL from the wedges. Nothing truly weird there.

The first act was a couple of tunes in when the trouble started. Feedback started building up, getting progressively worse until a mic on an acoustic guitar blasted off with a shriek that drove the input into clipping. I quietly rolled my eyes at the FOH engineer, thinking that they were winding things up without any necessity. At the same time, the lead performer got on the mic and asked for the gains on everything to be dropped. I did so, not believing that anything was wrong with monitor world, but definitely wanting to make an audible change for the purposes of keeping everybody calm. I mean, hey, FOH was not to be trusted. (This is a general rule. If you’re on monitor duty, FOH is the problem. If you’re on FOH, monitor beach is at fault. If everything is fine for audio, look out! Somebody in lighting is about to screw up.)

Anyway.

Things did indeed settle down, so I thought, “Now we can get monitor world back to where it’s supposed to be. The performers will be happy to hear themselves again.”

*Screeech!*

“Geeze, FOH…” I thought.

The stage manager asked me if there was anything I wanted to relay up to the FOH mix position. “Yeah, let’s pull the whole mix back 6 dB.” Everything seemed okay. I tried to get things back to normal in monitor world, and *Screech!*

Holy crap. The problem was on MY SIDE of the equation! As realization dawned, my brain actually started to work. There was no way that FOH would feed back in that frequency range, unless they were running at a ludicrous volume. It was monitor world. It couldn’t be anything else than monitor world. FOH was just fine…I was the idiot for the day! I had given FOH a “rusty halo,” which is the assumption of continuing inadequacy after a bad experience. Sometimes people deserve a rusty halo, and sometimes not. This was a definite case of “not.”

I’m still not sure quite what happened. The only explanation that seems at all reasonable to me is that the powered wedges we were using somehow underwent an unexpected increase in onboard gain. How that was precipitated, I can’t really guess, though the monitors that seemed to be giving me trouble were exposed to heat and sun until shortly before the trouble began. (A general cooldown of the components in the boxes seems like a farfetched reason to me, but that variable does correlate with the problem appearing. Correlation is not necessarily causation, but still.)

It was revealed later that the monitor wedges we used almost always seem to do something strange to the house crew. We say that it’s a poor craftsman who blames their tools, but if your tool is inadequate or dangerous then you can’t possibly do your best work. My guess is that the personnel at the venue are perfectly adequate to their tasks, and faulty equipment is their downfall. The same thing happened to me as what I imagine happened to them: They had things working perfectly well at soundcheck time, and then the wedges launched themselves into orbit. “The monitors were SO LOUD” had just become part of my own reality, which leads me to believe that I encountered the same issue as they did the previous year.

In the end, though, the important lesson was that I didn’t take the appropriate actions at an appropriate speed, because I was assuming that my side of the mix could not possibly be at fault. No! Your side of the show can ALWAYS be the problem. Look. Listen. Consider. Act.