So, my last article was precipitated by a question asked by Dee from The Black Smoke Gypsy Band. The group was debating whether to go direct with their electric guitars (in some way) or just mic the cabs. The question had inspired a bit of back and forth in the band, and Dee wanted to know what the right answer was.

Of course, I answered him with what I knew to be the most correct answer in pro-audio: “It depends.”

That’s also the most frustrating and infuriating answer.

The conversation didn’t stop there, though. A tech can’t just throw “It depends” at someone and walk off. You then have to talk about what might work for the questioner, and why.

Micing A Cab: Reliable and (Relatively) Simple

In my article about looking at electric guitar rigs as a kind of vocal (or any other acoustic instrument), I got at the idea that sticking a microphone in the area where “the noise comes out” is a simple and effective choice. All the questions of exactly how an instrument makes the sound it does are back-burnered. You just figure out where enough, decent-sounding level is present, and stick your transducer there.

A transducer is a device that converts one form of energy into another, corresponding form of energy. Mics transduce sound pressure waves into electrical signals. Speakers transduce electrical signals into sound pressure waves.

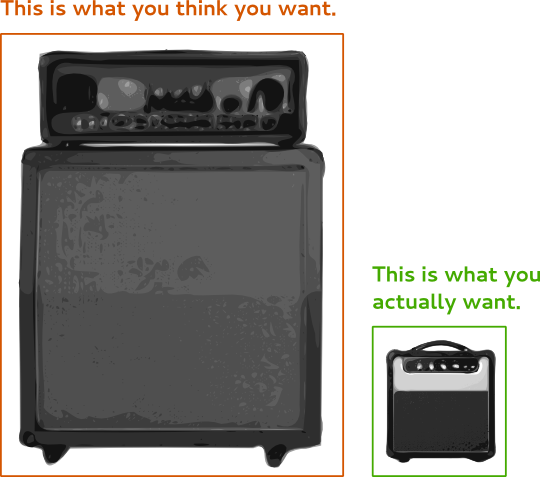

With the electric guitar as we have come to know it, the sound almost always comes out of a loudspeaker that’s mounted in a cabinet. That cabinet may also house an amplifier (a “combo”), or it might be part of a “stack” with a separate amplifier “head.” In any case, you don’t necessarily have to spend a lot of time philosophizing. The sound comes out of the speakers, so you mic the speakers.

Now, I don’t want to downplay the possible complexities of micing a guitar cab. Indeed, a lot of ink (and sometimes blood) has been spilled on all the intricacies that you can get into when micing a guitar rig:

Should you pick the best-sounding loudspeaker and put the mic up close?

If the mic is close to the cone, what area of the cone should it be closest to? (The dust cap area usually has more high-frequency information than the cone edges.) Should the mic diaphragm be parallel to the baffle? At an angle? Which mic should you use anyway? Should you use more than one mic? Should you try to time-align those mics, or should you pull one back slightly so that phase effects cancel out the frequencies you dislike?

…or, should you pull the mic back far enough to get the whole cab? (This rarely happens in small-venue work, but hey, you never know.)

Things can get very wooly.

For a sound reinforcement human, a lot of the time you end up making choices that are based on simple utility, and not “the very best sound possible, ever.” You close-mic a cone because you need maximum separation between the guitar and everything else making noise on stage. You pick the cone you do because you can get the mic stand in the right place easily, and because the mic setup will be the least in the way of the guitar player (and everybody else). You go for a placement that’s somewhere between the dust-cap crease and cone edge, figuring EQ will fix anything you don’t like.

Anyway.

Why mic a guitar cab? Why make that choice over other choices?

In the end, it comes down to this:

You should definitely use a mic for electric guitar if the specific sound produced by specific speakers in a specific cab is a crucial and non-replicable part of the guitar player’s sound.

See, electric guitar players can be incredibly choosy about their sound. Pretty much everything has an effect. There are folks who will spend days (if not more) trying to figure out which material for a pick has the best sound when used with their setup.

I’m dead serious.

In some cases, a critical, irreplaceable part of a guitar player’s sound is a certain brand and make of loudspeaker, with a certain amount of “miles” on it, with a certain amount of power flowing through it, that has been bolted into a specific kind of cabinet. If you were to even do something like replacing that speaker with a brand-new unit of the same model, their tone just wouldn’t be there.

You have to mic that. There’s no way around it. All other tricks and tactics are unacceptable.

However!

There are plenty of guitar players for whom this is not the case. There are lots of folks who like the sound of their cab just fine, but who aren’t “married” to its very specific effect on their overall sound.

So, to restate, you definitely want to mic an electric guitar rig if you are unable to get a sound that’s acceptable via some other method.

(Whether or not a guitar player having “their sound” is a good/ bad/ selfish/ team oriented/ stupid/ smart/ pleasant/ unpleasant/ crazy/ sane/ impossible/ doable thing in the context of the band in a particular venue is a whole other question, by the way.)

Going Direct: Might Be Easy, Might Be Hard

There’s a lot of mythology that goes around in guitar circles regarding the practice of going direct. It usually boils down to “going direct sucks.”

Horsefeathers.

If you want to hear a direct-in guitar that sounds good, just come on down to Fats Grill when Blues 66 is playing. Leroy’s guitar sound has a workable bottom end, a plenty-usable midrange growl (that I sometimes add to a bit, depending on the night), and a top end free of annoying hash and sizzle (that I sometimes low-pass anyway, again, depending on the night). He has no amp – just a POD HD…something…could be a 500.

It sounds like guitar to me, anyway. Nobody’s ever complained about it. The same thing was true for a band I used to work for, called Puddlestone. We ran the guitar processor through a cab-sim DI. It sounded fine. Great, even.

The point is that going direct with an electric guitar is entirely possible. You just have to use the right tools, and know which part of the signal chain you want to pull the line from.

So, where do you want to go to get that signal split?

When running an electric guitar direct to the console, you should take your signal at some point that is post the devices that have the greatest contribution to the essential components of the player’s sound.

This actually holds true for micing, because (as I said), the loudspeakers and cabinet may be an essential component of the player’s tone. If they are, then you have to get your signal “post” the loudspeaker. That means a mic.

In other situations, though, you have a number of different possibilities. For some folks, the essential components of their sound are created through processing. This processing may happen through stompboxes, or a rackmount processor, or both. When that’s the case, you need to take your split from a point that’s downstream of the processing chain, usually straight from the output of that process chain.

For other players, an essential component of their sound is the power amplification itself. There are coveted guitar amplifiers that produce a signature tone by driving, a power tube (or tubes) into saturation. If that saturation is an essential to the guitar player’s sound – not just a nice extra, but a critical piece of the puzzle – then you need to find a way to take a split from the output of the power amplification section. You can do this with a DI that has a 20+ dB PAD (Pre Attenuation Device) included, along with a parallel output to feed a cabinet. The parallel output is very important, because:

If you take a split from a point post the power amp, you must be very careful that an appropriate load is still being presented to the amplifier. Failure to do so can mean a costly repair.

Transformer-coupled amplifiers must have a minimum load present, and that load must be able to dissipate the power from the amplifier. Otherwise, the output transformer can be cooked by an internal arc, or other components can be wrecked by “flyback” voltage. When it comes to putting a DI on a power-amp output, you’re connecting a device that probably is NOT going to be seen as a proper load. Most modern, solid-state amplifiers don’t exhibit this behavior, because they don’t use output transformers, BUT ASSUME NOTHING.

When in doubt, parallel connect a suitable load to the amp.

Now – there’s one more thing about going direct.

Remember up there where I said that you have to use the right tools? This is an essential of getting a direct signal that actually sounds good. A generic, run of the mill DI box is not, in itself and without help, a sufficiently good tool for this job.

Why?

It all comes back around to those loudspeakers in guitar cabs.

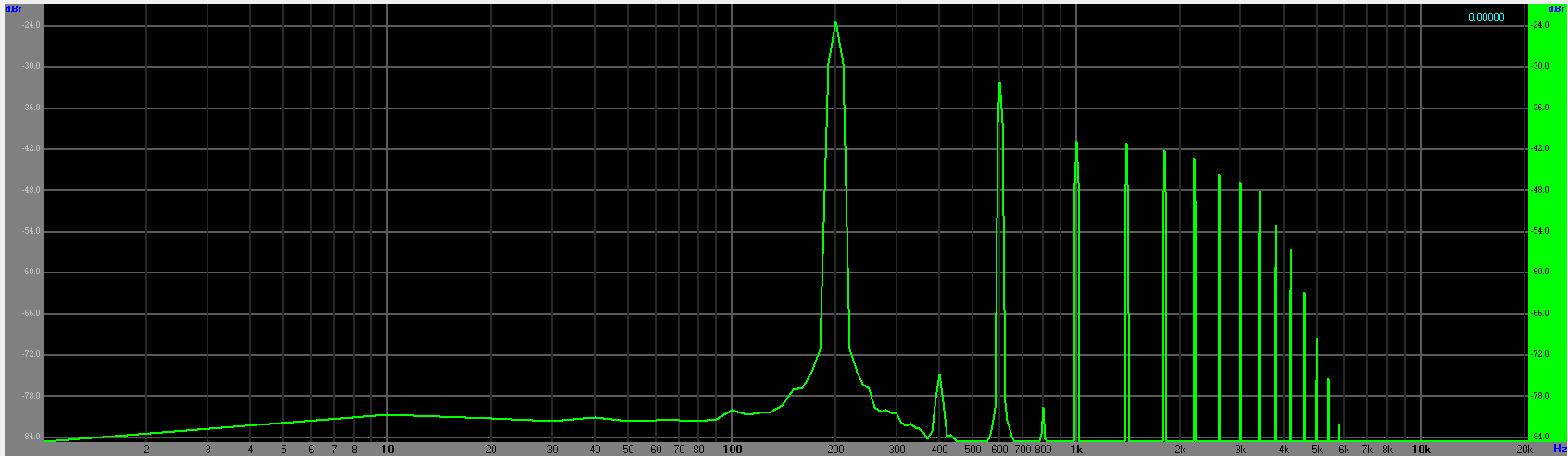

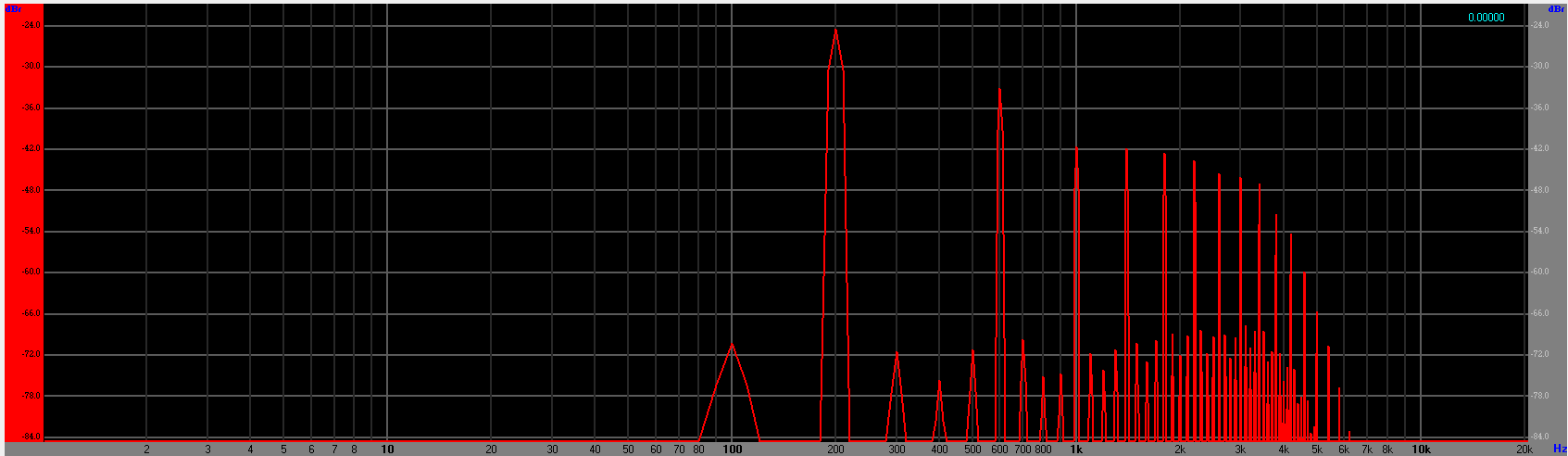

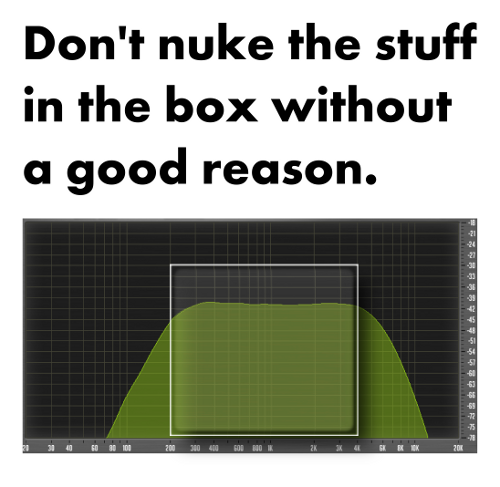

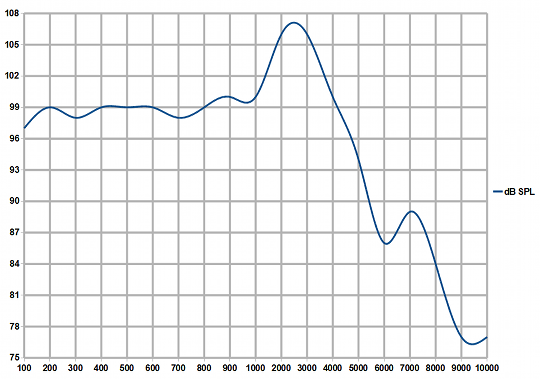

Your average guitar loudspeaker starts significantly rolling off the high frequency information in the signal after about 3 – 4 kHz or so. For example, here’s a frequency response graph that I made from data provided by Eminence for their “Red, White, and Blues” loudspeaker. After about 3 kHz, the frequency response is “goin’ downhill in a decent hurry.”

This rolloff is a critical component of what we know as “the electric guitar sound.” The problem is that a half-decent, bog-standard DI doesn’t roll off the high end. Even cheap ones can be essentially “flat” to 20 kHz. The basic DI actually preserves high-frequency information that the basic guitar speaker just chucks out the window (to one degree or another). This is why a lot of people think that direct-fed electric guitar “just sounds bad – all fizzy and high endy.” That’s actually what a guitar signal is, right up until it gets pumped through a loudspeaker.

Whaddya gonna do?

Some guitar processors have a dedicated direct out. These direct outs almost always have “cab simulation” applied, and so they sound reasonably like a miced rig without any other intervention. The fancier they get, the more they take into account the effects of different speakers loaded into different cabinets. Some even simulate different mics. Some even add a bit of “room” sound to the mix. Most importantly, though, they low pass the raw signal in a way that’s similar to a loudspeaker.

If all you’ve got is a basic DI that’s pulling a signal from somewhere, there’s still hope. If you can find an EQ to insert on the guitar channel, one that has a sweepable low-pass filter, you may be able to “build your own” cab simulator. Just twist that frequency selector knob until you get the frequency in the neighborhood of 4 kHz, and then tweak a bit more until your taste is as satisfied as possible. From there, you can do more shaping with other EQ bands.

To close, I’m going to leave you with some bullet points about when it’s good to attempt a proper DI solution. Remember that there’s an assumption here: You’ve already determined that any particular cabinet is not an absolutely crucial part of the guitar player’s sound:

- If the amp and cab sound terrible and/ or painful. (It can happen to anyone. I’ve heard some ostensibly all-tube rigs that sounded dreadfully screechy.)

- When you need to run high monitor levels with the guitar without worrying about mic feedback. (This does happen, just not that often.)

- When you can’t get good separation between the guitar rig and everything else on stage. (This can happen when a guitar rig is run a bit quietly, and then a bunch of guys who want to be disproportionately loud with everything else get on stage.)

- When you can’t get even a half-decent mic placement for some reason.

- When you don’t want to chew up stage space with mic stands.

- You think it would be cool to try something different, and the player is on board with that idea.

Micing can be done well, and direct input can be done well. You just have to figure out what’s appropriate, and then execute your chosen strategy in the right way.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Very reliable, but not the only valid technique.

Very reliable, but not the only valid technique.