Custom-made digital consoles have incredible power, but they aren’t for everybody.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

I’ve been a huge fan of digital consoles since about 2001. Back when I was studying at The Conservatory of Recording Arts and Sciences, it took one day in the digital studio to convince me that digital was the way to go. At the time, that room had two TMD-4000 consoles cascaded together. The functionality of those two consoles rivaled that of the much, much, much, much, much, much, (am I going to say, “much,” again? YES!), much more expensive SSL 4056 in the “A” room next door.

Now, I’m not here to argue about sonics. Having heard audio in both the digital room and Studio A, I can tell you that things sounded “just fine” in both places. Some folks might want to make a huge deal out of which consoles seem to sound better than other consoles. That’s not what I’m here to do. What I’m talking about here is functionality – the kinds of nifty tricks that different consoles can pull off.

Anyway, my first digital console was a DM-24. I now have two of them, actually.

I dropped the first one on concrete during an event load-in.

That DM-24 still works pretty well, surprisingly.

The Next Step

Fast-forward to 2011. I’m working at Fats Grill, and I’m tired of lugging my original, slightly-dinged-by-concrete DM-24 in and out of the place every week. (This was before I got my hands on the other DM, because it hadn’t been decommissioned yet. That’s another story.) It was time to get another console, but I couldn’t find anything I really liked at a price that I could justify.

Mostly, it was The Floyd Show’s fault.

This isn’t actually a tangent. Stick with me, folks.

See, we had featured the band, and the show had gone really well, but I had to submix a good chunk of their inputs. My DM was configured to act as both FOH and a virtual monitor console (more on that in another post), so I only had 15 channels that I could work with “natively” – with full, individual routing, and all that.

I wanted to be able to do the entire Floyd Show natively, on one console. I also wanted to keep full, virtual monitor console functionality. If I could do that, I figured that I could do the same for any other band that came through.

There were consoles in my price range with all the necessary analog inputs, but not enough actual channels or routing wizardry to do the virtual monitor thing. I also wasn’t fond of their overall implementation.

The single or cascaded console solutions that would do what I wanted were more than I could justify spending.

What’s a guy to do?

As it turns out, the next step in the “more bang for the buck” digital progression is to build your own console, using off-the-shelf audio interfaces and preamps. General computing platforms (like Windows) run on hardware that’s now powerful enough to stay responsive while handling lots of audio processing. That same hardware and software can also be made plenty reliable enough to function in a mission-critical environment like sound reinforcement.

The Magic

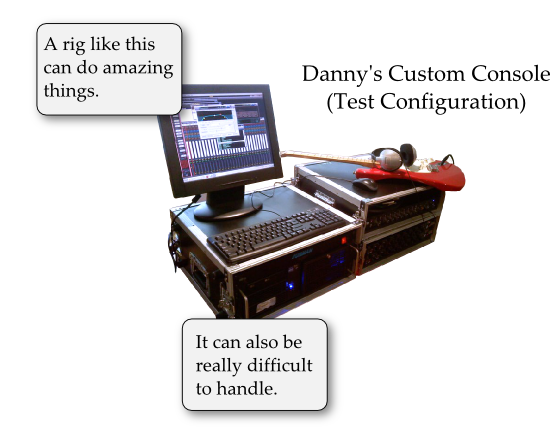

I ended up building a 24-input, 24-output rig, which originally ran Software Audio Console. I’ve since switched to Reaper, with some custom setup work to make the software more friendly to live work. (The “why” of that switch will be yet another post). On this kind of rig, the functionality available to an audio tech is extensive:

- You can have independent FOH and monitor consoles in one box. The monitor console can be completely independent of FOH – aside from your preamp gains – or you can make it dependent on FOH processing by making some routing changes. You could even make the monitor console dependent on only part of the FOH processing stack, if you’re willing to do some fancier routing.

- You could conceivably have multiple monitor consoles, configured independently. You could have multiple FOH consoles if you so desired. The only limit is how much processing the computer platform can do at an acceptable latency.

- You can have as many monitor sends, mix feeds, and cue buses as you have physical outputs available.

- Any regular channel on the console can have sends or be configured as a bus receive. Any channel. If you need full matrix output functionality, all you have to do is add the appropriate sends to the appropriate channels that are receiving other channels and feeding an output. If you need another bus, you just add one.

- Since all your console outputs and buses can be regular channels, you can insert any processing on those channels that you please. None of this, “you can’t have that kind of EQ in that context because the engineering team didn’t think it was really important” stuff.

- Drag and drop is available for all kinds of things. If you want to copy an EQ configuration to another channel, you just grab the EQ plug that’s setup properly, plop it into the target channel’s stack, delete the old EQ, and drag the new EQ to the proper spot. You can do the same for sends.

- The channel processing stack is incredibly configurable. If you want an EQ to come before a compressor, you can make that happen. If you change your mind, you can reorder the channel processing stack by drag and drop. If you want to have a special EQ that wasn’t part of the main audio chain, but instead does something wild with a parametric filter and then passes its output to a gate key or compressor sidechain, you can do that. You can have two extreme EQ setups that process in parallel. You can have a delay and reverb on a single channel that process in parallel, so that You don’t have to use two buses to address them.

- For channel processing, you can use any plugin you want – as long as you don’t add noticeable latency to the system of course. The “native” plugs that come with Reaper are killer, by the way:

- The gate has a key input, hysteresis, and can be made into an expander with a simple adjustment to a “dry signal” control.

- The compressor has a sidechain input, and also has a “dry signal” control, which means you can do parallel compression right in a single channel.

- The EQ has as many bands of EQ as you want. It includes peaking, shelving, notch, bandpass, and hi/ low pass filters.

- You can have permanent groups for channel faders and mutes, or you can get a temporary group by just multi-selecting what you want. (In fact, I use the temporary grouping a lot more than the assigned group functions.)

- You can save as many mixes and projects as the host computer can hold, with any system-legal filename that you want, in any hierarchy that you want.

- You can set up a VNC-based remote control system, as long as doing so doesn’t overload the system’s ability to process.

- Since the whole thing is driven by an audio interface, you can always swap for another one if the current unit has an issue, or you want to try something different.

- If you want more I/O, all you have to do is get an interface with more I/O, or cascade the current unit if that’s supported. You’re not tied to a manufacturer’s choice as to how much connectivity to include.

- If you want a control surface, you can add one. You have all kinds of choices, from cheap to extravagant.

- If the basic controls break, mice, trackballs and keyboards are only slightly more expensive than dirt. In the same vein, as long as you have a pointing device and keyboard attached, you effectively have a fallback control surface if the fancy one has a problem.

- If you want a better screen, you can get one. Or two. Or as many as your video card can support.

- You can multitrack record any show at any time, at a moment’s notice. You can even record to max-quality OGG files, and save a lot of disk space without a huge loss in audio quality.

- You could do an automated mix if you wanted, with a bit of planning and setup.

I’m sure that, somewhere, you can get a prebuilt digital console with all of this functionality. I just can’t think of anywhere that you can get it for less than $20,000 or so. If I remember correctly, the complete build price for the rig that I’ve just described is about $3000.

What To Be Careful Of

With everything I’ve laid out in the list above, you can probably tell that I’m pretty sold on this whole concept. Having all the functionality that my rig provides means that I can do all kinds of things that aren’t really expected in a small venue context – the most notable thing probably being that I have an independent monitor console, and lots of mixes to work with.

Even with all the positives, it’s important that I tell you about the risks and, shall we say, contraindications for putting together a rig like this:

- This probably should not be your first mixing console. All the options and flexibility can be overwhelming for people who are just starting to learn the craft of live audio.

- If big chunks of the terminology I’ve used above seem foreign to you, you should definitely do some homework before you try one of these rigs. Otherwise, you may be bewildered, or start doing things without knowing why you’re doing them.

- If you don’t have a great grasp of how signal flows in a mix rig, this kind of setup isn’t the right choice. A lot of the system’s magic comes from being able to throw audio around in all kinds of ways, and you need to know exactly what you’re doing and why you’re doing it. (I would rate myself as having professional-level competence in terms of understanding signal flow, and I can still back myself into a corner when I forget to think things through.)

- If your mix rig needs to be used by lots of different audio techs, especially BEs (Band Engineers), this kind of mix system is a bad choice. Very few people use them at the moment, and they’re not what most BEs expect when they roll up to a venue.

- Rigs like this aren’t likely to be acceptable on riders anytime soon.

- If you aren’t comfortable with digging around in computer hardware and software, you should think twice about diving into a rig like this.

- If you don’t have any experience with installing DAW hardware and software, and what can go wrong with DAW setups, you should allow a lot of time for getting your rig running. Or, just get a traditional console.

- If you aren’t keen on doing your own testing, this kind of system probably isn’t for you.

- If you can’t get comfortable with the idea that there’s no support except for yourself and what you can find online, this idea is probably something to skip.

- If you’re absolutely sold on working a lot of controls at the same time, you either need to attach and configure a really good control surface, or just get a regular console.

- These rigs tend to be a bit slower to operate than traditional consoles, in terms of user interface. If you’re not okay with that, you either need to put in a good control surface, or just stick with what you’re fast on.

- Even though you can save money overall on these systems, you need to spend dough on the important bits. USB interfaces are cheap, but getting decent latency out of them can be hard or even impossible. Firewire or PCI is the way to go.

With all that said, I just can’t help but be a bit giddy about how unconventional and powerful systems like these can be.

I’ll even help you build one, if you’re willing to throw some money my way. 🙂