Accessible recording gear means you don’t have to measure “live” if you don’t want to.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

I’m not an audio ninja. If you make a subtle change to a system EQ while the system is having pink noise run through it, I may or may not be able to tell that you’ve made a change, or I may not be able to tell you how wide or deep a filter you used. At the same time, I highly recognize the value of pink noise as an input to analysis systems.

“Wait! WAIT!,” I can hear you shouting, “What the heck are you talking about?”

I’m talking about measuring things. Objectivity. Using tools to figure out – to whatever extent is possible – exactly what is going on with an audio system. Audio humans use function and noise generators for measurement because of their predictability. For instance, unlike a recording of a song, I know that pink noise has equal power per octave and all audible frequencies present at any given moment. (White noise has equal power PER FREQUENCY, which means that each octave has twice as much power as the previous octave.)

If that paragraph sounded a little foreign to you, then don’t panic. Audio analysis is a GINORMOUS topic, with lots of pitfalls and blind corners. At the same time, I have a special place in my heart for objective measurement of audio devices. I get the “warm-n-fuzzies” for measurement traces because they are, in my mind, a tool for directly opposing a lot of the false mythology and bogus claims encountered in the business of sound.

Anyway.

Measurement is a great tool for dialing in live-sound rigs of all sorts. Because of its objectivity (assuming you actually use your measurement system correctly), it helps to calibrate your ears. You can look at a trace, listen to what something generating that trace sounds like, and have a reference point to work from. If you have a tendency to carve giant holes in a PA system’s frequency response when tuning by ear, measurement can help tame your overzealousness. If you’re not quite sure where that annoying, harsh, grating, high-mid peak is, measurement can help you find it and fix it.

…and one of the coolest things that I’ve discovered in recent years is that you don’t necessarily have to measure a system “live.” Offline measurement and tuning is much more possible than it ever has been before – mostly because digital tech has made recording so accessible.

How It Used To Be And Often Still Is

Back in the day, it was relatively expensive (as well as rather space-intensive and weight-intensive) to bring recording capabilities along with a PA system. Compact recording devices had limited capabilities, especially in terms of editing. Splicing tape while wrangling a PA wasn’t something that was going to happen.

As a result, if you wanted to tune a PA with the help of some kind of analyzer, you had to actually run a signal through the PA, into a measurement mic, and into the analysis device.

The sound you were measuring had to be audible. Very audible, actually, because test signals have to drown out the ambient noise in the room to be really usable. Sounds other than the test signal being audible to the measurement mic mean that your measurement’s accuracy is corrupted.

So, if you were using noise, the upshot was that you and everybody else in the room had to listen to a rather unpleasant blast of sound for as long as it took to get a reference tuning in place. It’s not much fun (unless you’re the person doing the work), and you can’t do it everywhere. Even when using a system that can take inputs other than noise, you still had to measure and make your adjustments “live,” with an audible signal in the room.

Taking A Different Route

The beautiful thing about today’s technology is that we have alternatives. In some cases, you might prefer to do a “fully live” tuning of a PA system or monitor rig – but if you’d prefer a different approach, it’s entirely possible.

It’s all because of how easy recording is, really.

The thing is, any audio-analysis system doesn’t really care where its input comes from. An analyzer really isn’t bothered about if its information is coming from a live measurement mic, or if the information is a recording of what came out of that measurement mic. All the analyzer knows is that some signal is being presented to it.

If you’re working with a single-input analyzer, offline measurement and tuning is basically about getting the “housekeeping” right:

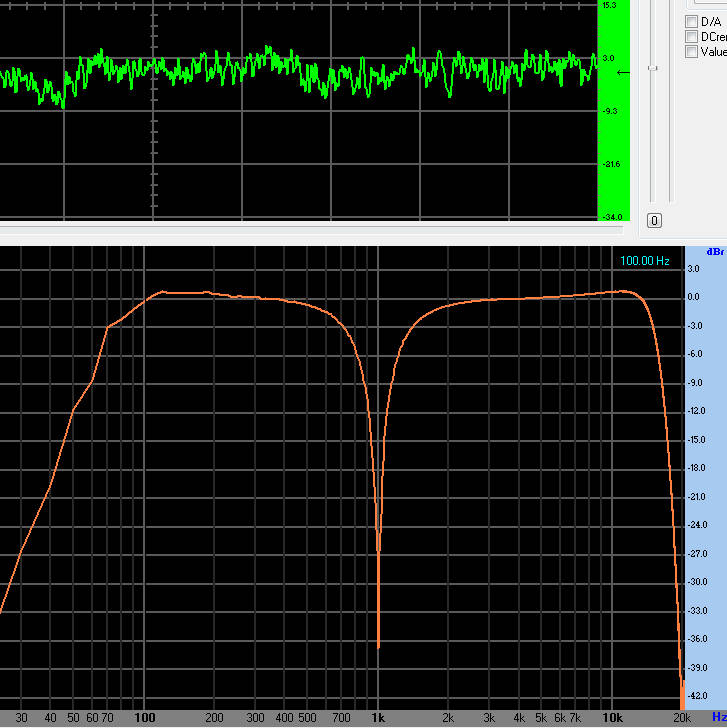

- Run your measurement signal to the analyzer, without any intervening EQ or other processing. If that signal is supposed to give you a “flat” measurement trace, then make sure it does. You need a reference point that you can trust.

- Now, disconnect the signal from the analyzer and route that same measurement signal through the audio device(s) that you want to test. This includes the measurement mic if you’re working on something that produces acoustical output – like monitor wedges or an FOH (Front Of House) PA. The actual thing that delivers the signal to be captured and analyzed is the “device-under-test.” For the rest of this article, I’m effectively assuming that the device-under-test is a measurement mic.

- Connect the output of the device-under-test to something that can record the signal.

- Record at least several seconds of your test signal passing through what you want to analyze. I recommend getting at least 30 seconds of recorded audio. Remember that the measurement-signal to ambient-noise ratio needs to be pretty high – ideally, you shouldn’t be able to hear ambient noise when your test signal is running.

- If at all possible, find a way to loop the playback of your measurement recording. This will let you work without having to restart the playback all the time.

- Run the measurement recording through the signal chain that you will use to process the audio in a live setting.

- Send the output of that signal chain to the analyzer, but do NOT actually send the output to the PA or monitor rig.

Because the recorded measurement isn’t being sent to the “acoustical endpoints” (the loudspeakers) of your FOH PA or monitor rig, you don’t have to listen to loud noise while you adjust. As you make changes to, say, your system EQ, you’ll see the analyzer react. Get a curve that you’re comfortable with, and then you can reconnect your amps and speakers for a reality check. (Getting a reality check of what you just did in silence is VERY important – doubly so if you made drastic changes somewhere.)

Dual-FFT

So, all of that up there is fine and good, but…what if you’re not working with a simple, single input analyzer? What if you’re using a dual-FFT system like SMAART, EASERA, or Visual Analyzer?

Well, you can still do offline measurement, but things get a touch more complicated.

A dual-FFT (or “transfer function”) analysis system works by comparing a reference signal to a measurement signal. For offline measurement to work with comparative analysis, you have to be able to play back a copy of the EXACT signal that you’ll be using for measurement. You also have to be able to play that signal in sync with your measurement recording, but on a separate channel.

For me, the easiest way to accomplish this is to have a pre-recorded (as opposed to “live generated”) test signal. I set things up so that I can record the device-under-test while playing back the test signal through that device. For example, I could have the pre-recorded test signal on channel one, connect my measurement device so that it’s set to record on channel two, hit “record,” and be off to the races.

There is an additional wrinkle, though – time-alignment. Dual-FFT analyzers give skewed results if the measurement signal is early or late when compared to the reference signal, because, as far as the analyzer is concerned, the measurement signal is diverging from the reference. Of course, any measured signal is going to diverge from the reference, but you don’t want unnecessary divergence to corrupt the analysis. The problem, though, is that your test signal takes time to travel from the loudspeaker to the measurement microphone. The measurement recording, when compared to the reference recording, is inherently “late” because of this propagation delay.

Systems like SMAART and EASERA have a way of doing automatic delay compensation in a quick and painless way, but Visual Analyzer doesn’t. If your software doesn’t have an internal method for delay compensation, you’ll need to do it manually. This means:

- Preparing a test signal that includes an audible click, pop, or other transient that tells you where the signal starts.

- After recording the measurement signal, you’ll need to use that click or pop to line up the measurement recording with the test-signal, in terms of time. The more accurate the “sync,” the more stable your measurement trace will be.

If you’d rather not make your own test signal, you’re welcome to download and use this one. The “click” at the beginning is several cycles of a 2 kHz tone.

The bottom line is that you can certainly do “live” measurements if you want to, but you also have the option of capturing your measurement for “silent” tweaking. It’s ultimately about doing what’s best for your particular application…and remembering to do that “reality check” listen of your modifications, of course.