If I’m going to editorialize on this, I first need to be clear about one thing: I’m not against certain things being taken on faith. There are plenty of assumptions in my life that can’t be empirically tested. I don’t have a problem with that in any way. I subscribe quite strongly to that old saw:

You ARE entitled to your opinion. You ARE NOT entitled to your own set of “facts.”

But, of course, that means that I subscribe to both sides of it. As I’ve gotten farther and farther along in the show-production craft, especially the audio part, I’ve gotten more and more dismayed with how opinion is used in place of fact. I’ve found myself getting more and more “riled” with discussions where all kinds of assertions are used as conversational currency, unbacked by any visible, objective defense. People claim something, and I want to shout, “Where’s your data, dude? Back that up. Defend your answer!”

I would say that part of the problem lies in how we describe the job. We have (or at least had) the tendency to say, “It’s a mix of art and science.” Unfortunately, my impression is that this has come to be a sort of handwaving of the science part. “Oh…the nuts and bolts of how things work aren’t all that important. If you’re pleased with the results, then you’re okay.” While this is a fair statement on the grounds of having reached a workable endpoint through unorthodox or uneducated means, I worry about the disservice it does to the craft when it’s overapplied.

To be brutally frank, I wish the “mix of art and science” thing would go away. I would replace it with, “What we’re doing is science in the service of art.”

Everything that an audio human does or encounters is precipitated by physics – and not “exotic” physics, either. We’re talking about Newtonian interactions and well-understood electronics here, not quantum entanglement, subatomic particles, and speeds approaching that of light. The processes that cause sound stuff to happen are entirely understandable, wieldable, and measurable by ordinary humans – and this means that audio is not any sort of arcane magic. A show’s audio coming off well or poorly always has a logical explanation, even if that explanation is obscure at the time.

I Should Be Able To Measure It

Here’s where the rubber truly meets the road on all this.

There seems to be a very small number of audio humans who are willing to do any actual science. That is to say, investigating something in such a way as to get objective, quantitative data. This causes huge problems with troubleshooting, consulting, and system building. All manner of rabbit trails may be followed while trying to fix something, and all manner of moneys are spent in the process, but the problem stays un-fixed. Our enormous pool of myth, legend, and hearsay seems to be great for swatting at symptoms, but it’s not so hot for tracking down the root cause of what’s ailing us.

Part of our problem – I include myself because I AM susceptible – is that listening is easy and measuring is hard. Or, rather, scientific measuring is hard.

Listening tests of all kinds are ubiquitous in this business. They’re easy to do, because they aren’t demanding in terms of setup or parameter control. You try to get your levels matched, setup some fast signal switching, maybe (if you’re very lucky) make it all double-blind so that nobody knows what switch setting corresponds to a particular signal, and go for it.

Direct observation via the senses has been used in science for a long time. It’s not that it’s completely invalid. It’s just that it has problems. The biggest problem is that our senses are interpreted through our brains, an organ which develops strong biases and filters information so that we don’t die. The next problem is that the experimental parameter control actually tends to be quite shoddy. In the worst cases, you get people claiming that, say, console A has a better sound than console B. But…they heard console A in one place, with one band, and console B in a totally different place with a totally different band. There’s no meaningful comparison, because the devices under test AND the test signals were different.

As a result, listening tests produce all kinds of impressions that aren’t actually helpful. Heck, we don’t even know what “sounds better” means. For this person over here, it means lots of high-frequency information. For some other person, it means a slight bass boost. This guy wants a touch of distortion that emphasizes the even-numbered harmonics. That gal wants a device that resembles a “straight wire” as much as possible. Nobody can even agree on what they like! You can’t actually get a rigorous comparison out of that sort of thing.

The flipside is, if we can actually hear it, we should be able to measure it. If a given input signal actually sounds different when listened to through different signal paths, then those signal paths MUST have different transfer functions. A measurement transducer that meets or exceeds the bandwidth and transient response of a human ear should be able to detect that output signal reliably. (A measurement mic that, at the very least, significantly exceeds the bandwidth of human hearing is only about $700.)

As I said, measuring – real measuring – is hard. If the analysis rig is setup incorrectly, we get unusable results, and it’s frighteningly easy to screw up an experimental procedure. Also, we have to be very, very defined about what we’re trying to measure. We have to start with an input signal that is EXACTLY the same for all measurements. None of this “we’ll set up the drums in this room, play them, then tear them down and set them up in this other room,” can be tolerated as valid. Then, we have to make every other parameter agree for each device being tested. No fair running one preamp closer to clipping than the other! (For example.)

Question Everything

So…what to do now?

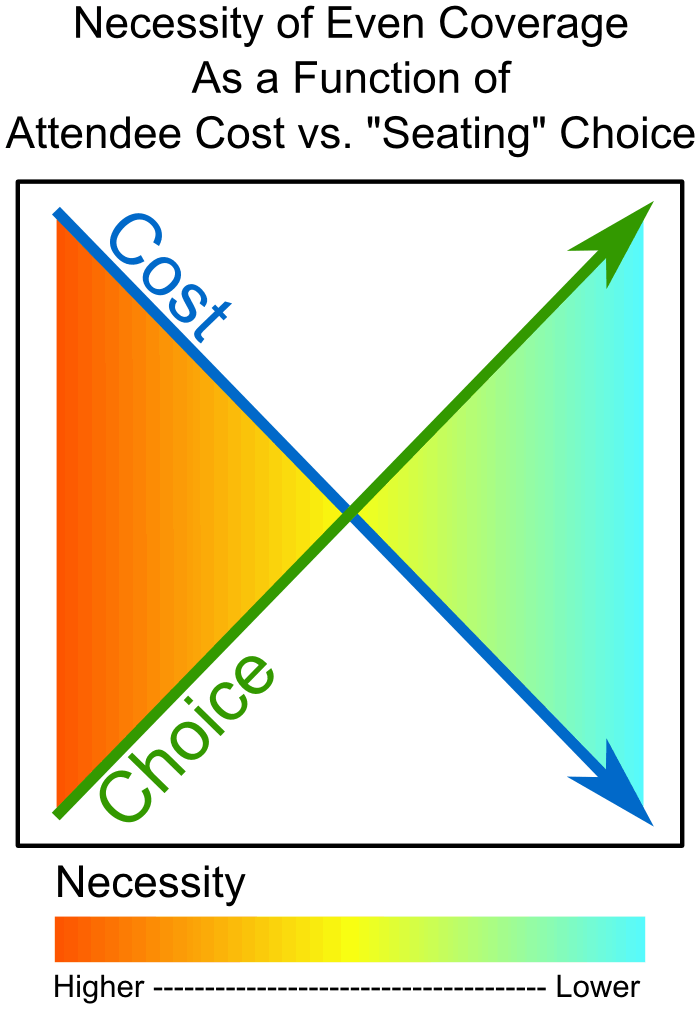

If I had to propose an initial solution to the problems I see (which may not be seen by others, because this is my own opinion – oh, the IRONY), I would NOT say that the solution is for everyone to graph everything. I don’t see that as being necessary. What I DO see as being necessary is for more production craftspersons to embrace their inner skeptic. The lesser amount of coherent explanation that’s attached to an assertion, the more we should doubt that assertion. We can even develop a “hierarchy of dubiousness.”

If something can be backed up with an actual experiment that produces quantitative data, that something is probably true until disproved by someone else running the same experiment. Failure to disclose the experimental procedure makes the measurement suspect however – how exactly did they arrive at the conclusion that the loudspeaker will tolerate 1 kW of continuous input? No details? Hmmm…

If a statement is made and backed up with an accepted scientific model, the statement is probably true…but should be examined to make sure the model was applied correctly. There are lots of people who know audio words, but not what those words really mean. Also, the model might change, though that’s unlikely in basic physics.

Experience and anecdotes (“I heard this thing, and I liked it better”) are individually valid, but only in the very limited context of the person relating them. A large set of similar experiences across a diverse range of people expands the validity of the declaration, however.

You get the idea.

The point is that a growing lack of desire to just accept any old statement about audio will, hopefully, start to weed out some of the mythological monsters that periodically stomp through the production-tech village. If the myths can’t propagate, they stand a chance of dying off. Maybe. A guy can hope.

So, question your peers. Question yourself. Especially if there’s a problem, and the proposed fix involves a significant amount of money, question the fix.

A group of us were once troubleshooting an issue. A producer wasn’t liking the sound quality he was getting from his mic. The discussion quickly turned to preamps, and whether he should save up to buy a whole new audio interface for his computer. It finally dawned on me that we hadn’t bothered to ask anything about how he was using the mic, and when I did ask, he stated that he was standing several feet from the unit. If that’s not a recipe for sound that can be described as “thin,” I don’t know what is. His problem had everything to do with the acoustic physics of using a microphone, and nothing substantial AT ALL to do with the preamp he was using.

A little bit of critical thinking can save you a good pile of cash, it would seem.

(By the way, I am biased like MAD against the the crowd that craves expensive mic pres, so be aware of that when I’m making assertions. Just to be fair. Question everything. Question EVERYTHING. Ask where the data is. Verify.)

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.