Not everyone will appreciate it, but staying calm during a show is a really good idea.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.I didn’t really come up with the title of this article. Washington Irving did. I’m pretty sure Washington Irving knew basically nothing about production for rock shows, but he knew about life – and rock shows follow the rules of life.

One of the rules of life is that panic can kill you. It especially kills you in pressure situations involving technical processes. The reason why is pretty simple: Panic shuts off your rational mind, and a technical process REQUIRES your rational mind. When the…stuff…hits the fan, and you’re driving an audio rig, frantic thrashing will not save you. It will, instead, dig you an even deeper pit.

Calmness, on the other hand, allows you to think. The suppression of a fight-or-flight response means that your mental process is freed of having to swim upstream against a barrage of terrified impulses. You get more solutions with less work, because you’re able to linearly piece together why you’ve just been bitten in your ample, fleshy rear. Maintaining a tranquil, logical flow of problem solving not only means that you’re likely to get the problem fixed, it also means that you’ve got a fighting chance at finding your root cause. If you find and fix your problem’s root cause, your problem will stay solved. If all you do is mask the failure in a fit of “band-aid sticking,” you’re going to get bitten again – and soon, probably.

Another thing to keep in mind is that your emotional state is infectious in multiple ways. The most obvious connection is the simple transfer of mindset. If you’re seen as being in charge of the show – the person flying the plane, as it were – then you’re also unconsciously perceived as having authority over how to interpret the situation. If you, the authority are losing your crap, then the signal is being sent that the loss of one’s crap is the appropriate response to the problem. Deep down, we humans have “herd mammal” software installed. It’s a side-effect of how we’re constructed. Under enough stress, our tendency is to run that software, which obeys the overall direction of the group.

And the group obeys the leader. So, lead well.

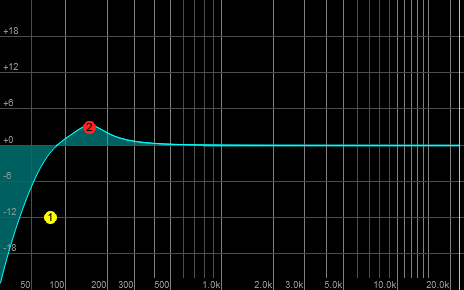

The more indirect way that emotional state transfers is through your actions which affect others. The musicians on deck are not, of course, oblivious to what you’re doing with the console and system processing. If you’re banging away without much direction, eventually you will do something that seriously gums up a musician’s performance. This is especially true if you’re wildly tweaking every monitor channel in sight. One second, things are a little weird due to a minor problem. Then, you panic and start futzing around with every send and mute you can reach, and things get even weirder. Maybe even unusable. You don’t want that.

The majestic grandeur of tranquility, on the other hand, embodies itself in making precise, deliberate changes that mess with the performance as little as possible. It is engaging in the scientific process, running experiments and noting the results at very high speed. Being deliberate DOES slow down individual actions, but the total solution arrives more quickly. You end up taking the direct route, instead of a million side trips.

It’s Not Easy, And Not Everybody Gets It

If this sounds like a tough discipline, that’s because it is. Even being aware of its importance, I still don’t always do it successfully. (And I’ve had LOTS of practice.)

Also, some folks confuse serenity with inattentiveness.

I once worked a show where a member of the audience was a far more “high-powered” audio human than myself. This person worked on big shows, with big teams, in big spaces. This person knew their stuff, without a doubt.

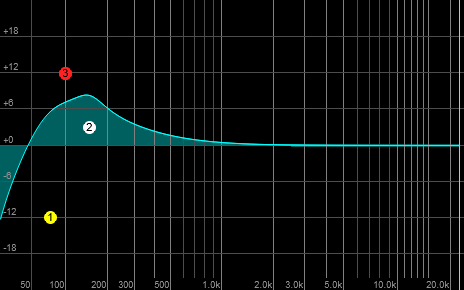

The problem, though, was that the show was hitting some snags. The band had been thrown together to do the gig, and while the effort was admirable, the results were a little ragged. The group was a little too loud for themselves, and monitor world was being thrown together on the fly. It was a battle to keep it all from flying off the handle, and the show was definitely trying to run away. I was trying to take my own advice, and combat the problems surgically. As much as the game of “feedback whack-a-mole” wasn’t all that aesthetically pleasing, I was steadily working towards getting things sorted out.

Unfortunately, to this other audio-human, I didn’t look like I was doing enough. Their preferred method was to sledgehammer a problem until it went away, and I was NOT sledgehammering. Therefore, I was “doing it wrong.”

We ended up doing some pretty wild things to the performers in the name of getting things under control. In my opinion, the result was that the show appeared to be MORE out of control, until our EQ and monitor send carpet-bombing campaign had smashed everything in sight.

The problem was “fixed,” but we had done a lot of damage in the process, all in the name of “looking busy.”

To this day, I think staying calm would have been better for that show. I think staying calm and working things out methodically is best for all shows. My considered advice is (to take a page from Dumbledore) that everyone should, please, not panic.