Monitors can be a beautiful thing. Handled well, they can elicit bright-eyed, enthusiastic approbations like “I’ve never heard myself so well!” and “That was the best sounding show EVER!” They can very easily be the difference between a mediocre set and a killer show, because of how much they can influence the musicians’ ability to play as a group.

I’ve said it to many people, and I’m pretty sure I’ve said it here: As an audio-human, I spend much more time worrying about monitor world than FOH (Front Of House). If something is wrong out front, I can hear it. If something is wrong in monitor world, I won’t hear it unless it’s REALLY wrong. Or spiraling out of control.

…and there’s the issue. Bad monitor mixes can do a lot of damage. They can make the show less fun for the musicians, or totally un-fun for the musicians, or even cause so much on stage wreckage that the show for the audience becomes a disaster. On top of that, the speed at which the sound on deck can go wrong can be startlingly high. If you’ve ever lost control of monitor world, or have been a musician in a situation where someone else has had monitor world “get away” from them, you know what I mean. When monitors become suckified, so too does life.

So – how does one unsuckify (or, even better, prevent suckification of) monitor world?

Foundational Issues To Prevent Suckification

Know The Inherent Limits On The Engineer’s Perception

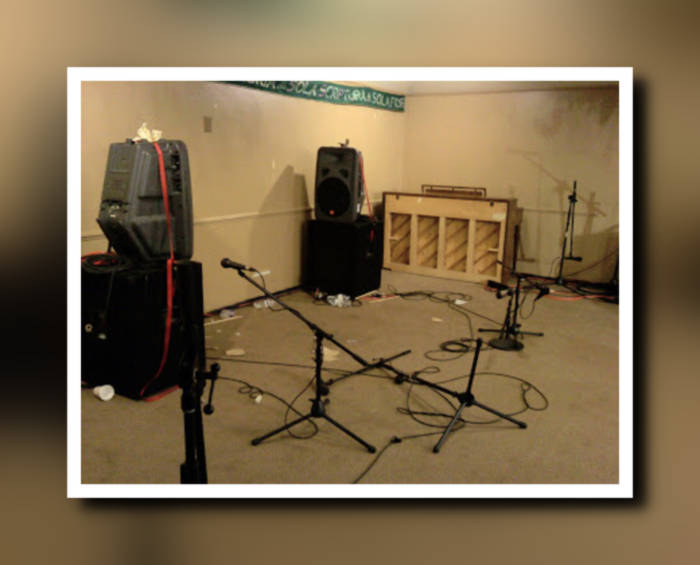

At the really high-class gigs, musicians and production techs alike are treated to a dedicated “monitor world” or “monitor beach.” This is an independent or semi-independent audio control rig that is used to mix the show for the musicians. There are even some cases where there are multiple monitor worlds, all run by separate people. These folks are likely to have a setup where they can quickly “solo” a particular monitor mix into their own set of in-ears, or a monitor wedge which is similar to what the musicians have. Obviously, this is very helpful to them in determining what a particular performer is hearing.

Even so, the monitor engineer is rarely in exactly the same spot as any particular musician. Consequently, if the musicians are on wedges, even listening to a cue wedge doesn’t exactly replicate the total acoustic situation being experienced by the players.

Now, imagine a typical small-venue gig. There’s probably one audio human doing everything, and they’re probably listening mostly to the FOH PA. The way that FOH combines with monitor world can be remarkably different out front versus on deck. If the engineer has a capable console, they can solo up a complete monitor mix, probably through a pair of headphones. (A cue wedge is pretty unlikely to have been set up. They’re expensive and consume space.) A headphone feed is better than nothing, but listening to a wedge mix in a set of cans only tells an operator so much. Especially when working on a drummer’s mix, listening to the feed through a set of headphones has limited utility. A guy or gal might set up a nicely balanced blend, but have no real way of knowing if that mix is even truly audible at the percussionist’s seat.

If you’re not so lucky as to have a flexible console, your audio human will be limited to soloing individual inputs.

The point is that, at most small-venue shows, an audio human at FOH can’t really be expected to know what a particular mix sounds like as a total acoustic event. Remote-controlled consoles can fix this temporarily, of course, but as soon as the operator leaves the deck…all bets are off. If you’re a musician, assume that the engineer does NOT have a thoroughly objective understanding of what you’re hearing. If you’re an audio human, make the same assumption about yourself. Having made those assumptions, be gentle with yourself and others. Recognize that anything “pre set” is just a wild guess, and further, recognize that trying to take a channel from “inaudible in a mix” to “audible” is going to take some work and cooperation.

Use Language That’s As Objective As Possible

Over the course of a career, audio humans create mental mappings between subjective statements and objective measurements. For instance, when I’m working with well-established monitor mixes, I translate requests like “Could I get just a little more guitar?” into “Could I get 3 dB more guitar?” This is a necessary thing for engineers to formulate for themselves, and it’s appropriate to expect that a pro-level operator has some ability to interpret subjective requests.

At the same time, though, it can make life much easier when everybody communicates using objective language. (Heck, it makes it easier if there’s two-way communication at all.)

For instance, let’s say you’re an audio human working with a performer on a monitor mix, and they ask you for “a little more guitar.” I strongly recommend making the change that you translate “a little more” as corresponding to, and then stating your change (in objective terms) over the talkback. Saying something like, “Okay, that’s 3 dB more guitar in mix 2” creates a helpful dialogue. If that 3 dB more guitar wasn’t enough, the stating of the change opens a door for the musician to say that they need more. Also, there’s an opportunity for the musician’s perception to become calibrated to an objective scale – meaning that they get an intuitive sense for what a certain dB boost “feels” like. Another opportunity that arises is for you and the musician to become calibrated to each other’s terminology.

Beyond that, a two-way dialogue fosters trust. If you’re working on monitors and are asked for a change, making a change and then stating what you did indicates that you are trying to fulfill the musician’s wishes. This, along with the understanding that gets built as the communication continues, helps to mentally place everybody on the same team.

For musicians, as you’re asking for changes in your monitor mixes, I strongly encourage you to state things in terms of a scale that the engineer can understand. You can often determine that scale by asking questions like, “What level is my vocal set at in my mix?” If the monitor sends are calibrated in decibels, the engineer will probably respond with a decibel number. If they’re calibrated in an arbitrary scale, then the reply will probably be an arbitrary number. Either way, you will have a reference point to use when asking for things, even if that reference point is a bit “coarse.” Even if all you’ve got is to request that something go from, say, “five to three,” that’s still functionally objective if the console is labeled using an arbitrary scale.

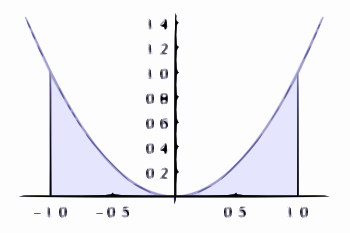

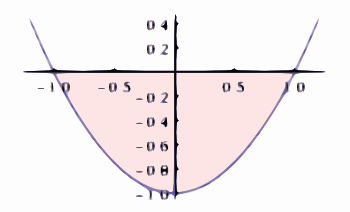

For decibels, a useful shorthand to remember is that 3 dB should be a noticeable change in level for something that’s already audible in your mix. “Three decibels” is a 2:1 power ratio, although you might personally feel that “twice as loud” is 6 dB (4:1) or even 10 dB (10:1).

Realtime Considerations To Prevent And Undo Suckification

Too Much Loop Gain, Too Much Volume

Any instrument or device that is substantially affected by the sound from a monitor wedge, and is being fed through that same wedge, is part of that mix’s “loop gain.” Microphones, guitars, basses, acoustic drums, and anything else that involves body or airborne resonance is a factor. When their output is put through a monitor speaker, these devices combine with the monitor signal path to form an acoustical, tuned circuit. In tuned circuits, the load impedance determines whether the circuit “rings.” As the load impedance drops, the circuit is more and more likely to ring or resonate for a longer time.

If that last bit made your eyes glaze over, don’t worry. The point is that more gain (turning something up in the mix) REDUCES the impedance, or opposition, to the flow of sound in the loop. As the acoustic impedance drops, the acoustic circuit is more likely to ring. You know, feed back. *SQEEEEEALLLL* *WHOOOOOwoowooooOOOM*

Anyway.

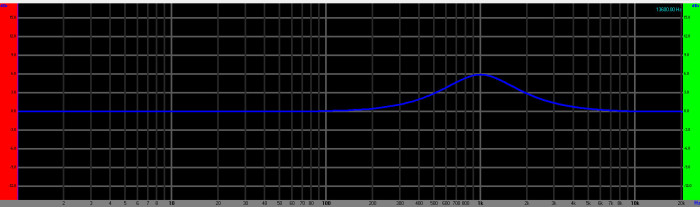

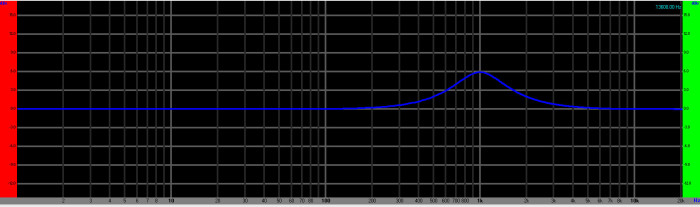

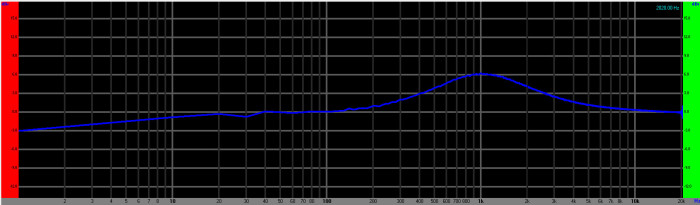

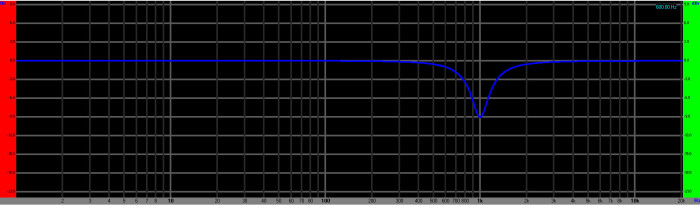

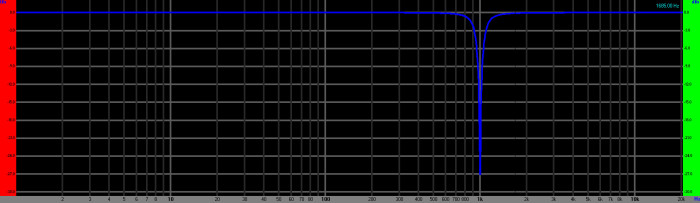

The thing for everybody to remember – audio humans and musicians alike – is that a monitor mix feeding a wedge becomes progressively more unstable as gain is added. As ringing sets in, the sound quality of the mix drops off. Sounds that should start and then stop quickly begin to “smear,” and with more gain, certain frequency ranges become “peaky” as they ring. Too much gain can sometimes begin to manifest itself as an overall tone that seems harsh and tiring, because sonic energy in an irritating range builds up and sustains itself for too long. Further instability results in audible feedback that, while self-correcting, sounds bad and can be hard for an operator to zero-in on. As instability increases further, the mix finally erupts into “runaway” feedback that’s both distracting and unnerving to everyone.

The fix, then is to keep each mix’s loop gain as low as possible. This often translates into keeping things OUT of the monitors.

As an example, there’s a phenomenon I’ve encountered many times where folks start with vocals that work…and then add a ton of other things to their feed. These other sources are often far more feedback resistant than their vocal mic can be, and so they can apply enough gain to end up with a rather loud monitor mix. Unfortunately, they fall in love with the sound of that loud mix, except for the vocals which have just been drowned. As a result, they ask for the vocals to be cranked up to match. The loop gain on the vocal mic increases, which destabilizes the mix, which makes monitor world harder to manage.

As an added “bonus,” that blastingly loud monitor mix is often VERY audible to everybody else on stage, which interferes with their mixes, which can cause everybody else to want their overall mix volume to go up, which increases loop gain, which… (You get the idea.)

The implication is that, if you’re having troubles with monitors, a good thing to do is to start pulling things out of the mixes. If the last thing you did before monitor world went bad was, say, adding gain to a vocal mic, try reversing that change and then rebuilding things to match the lower level.

And not to be harsh or combative, but if you’re a musician and you require high-gain monitors to even play at all, then what you really have is an arrangement, ensemble, ability, or equipment problem that is YOURS to fix. It is not an audio-human problem or a monitor-rig problem. It’s your problem. This doesn’t mean that an engineer won’t help you fix it, it just means that it’s not their ultimate responsibility.

Also, take notice of what I said up there: High-GAIN monitors. It is entirely possible to have a high-gain monitor situation without also having a lot of volume. For example, 80 dB SPL C is hardly “rock and roll” loud, but getting that output from a person who sings at the level of a whisper (50 – 60 dB SPL C) requires 20 – 30 dB of boost. For the acoustical circuits that I’ve encountered in small venues, that is definitely a high-gain situation. Gain is the relative level increase or decrease applied to a signal. Volume is the output associated with a signal level resultant from gain. They are related to each other, but the relationship isn’t fixed in terms of any particular gain setting.

Conflicting Frequency Content

Independent of being in a high-gain monitor conundrum, you can also have your day ruined by masking. Masking is what occurs when two sources with similar frequency content become overlaid. One source will tend to dominate the other, and you lose the ability to hear both sources at once. I’ve had this happen to me on numerous occasions with pianists and guitar players. They end up wanting to play at the same time, using substantially the same notes, and the sonic characteristics of the two instruments can be surprisingly close. What you get is either too-loud guitar, too-loud piano, or an indistinguishable mash of both.

In a monitor-mix situation, it’s helpful to identify when multiple sources are all trying to occupy the same sonic space. If sources can’t be distinguished from one another until one sound just gets obliterated, then you may have a frequency-content collision in progress. These collisions can result in volume wars, which can lead to high-gain situations, which result in the issues I talked about in the previous section. (Monitor problems are vicious creatures that breed like rabbits.)

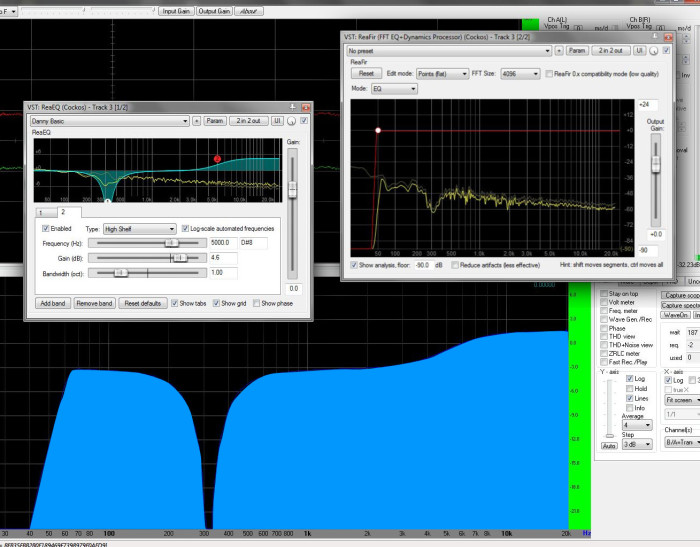

After being identified, frequency-content issues can be solved in a couple of different ways. One way is to use equalization to alter the sonic content of one source or another. For instance, a guitar and a bass might be stepping on each other. It might be decided that the bass sound is fine, but the guitar needs to change. In that case, you might end up rolling down the guitar’s bottom end, and giving the mids a push. Of course, you also have to decide where this change needs to take place. If everything was distinct before the monitor rig got involved, then some equalization change from the audio human is probably in order. If the problem largely existed before any monitor mixes were established, then the issue likely lies in tone choice or song arrangement. In that case, it’s up to the musicians.

One thing to be aware of is that many small-venue mix rigs have monitor sends derived from the same channel that feeds FOH. While this means that the engineer’s channel EQ can probably be used to help fix a frequency collision, it also means that the change will affect the FOH mix as well. If FOH and monitor world sound significantly different from each other, a channel EQ configuration that’s correct for monitor world may not be all that nice out front. Polite communication and compromise are necessary from both the musicians and the engineer in this case. (Certain technical tricks are also possible, like “multing” a problem source into a monitors-only channel.)

Lack Of Localization

Humans have two ears so that we can determine the location and direction of sounds. In music, one way for us to distinguish sources is for us to recognize those instruments as coming from different places. When localization information gets lost, then distinguishing between sources requires more separation in terms of overall volume and frequency content. If that separation isn’t possible to get, then things can become very muddled.

This relates to monitors in more than one way.

One way is a “too many things in one place that’s too loud” issue. In this instance, a monitor mix gets more and more put in it, and at a high enough volume that the monitor obscures the other sounds on deck. What the musician originally heard as multiple, individually localized sources is now a single source – the wedge. The loss of localization information may mean that frequency-content collisions become a problem, which may lead to a volume-war problem, which may lead to a loop-gain problem.

Another possible conundrum is “too much volume everywhere.” This happens when a particular source gets put through enough wedges at enough volume for it to feel as though that single source is everywhere. This can ruin localization for that particular source, which can also result in the whole cascade of problems that I’ve already alluded to.

Fixing a localization problem pretty much comes down having sounds occupy their own spatial point as much as possible. The first thing to do is to figure out if all the volume used for that particular source is actually necessary in each mix. If the volume is basically necessary, then it may be feasible to move that volume to a different (but nearby) monitor mix. For some of the players, that sound will get a little muddier and a touch quieter, but the increase in localization may offset those losses. If the volume really isn’t necessary, then things get much easier. All that’s required is to pull back the monitor feeds from that source until localization becomes established again.

It’s worth noting that “extreme” cases are possible. In those situations, it may be necessary to find a way to generate the necessary volume from a single, localized source that’s audible to everyone on the deck. A well placed sidefill can do this, and an instrument amplifier in the correct position can take this role if a regular sidefill can’t be conjured up.

Wrapping Up

This can be a lot to take in, and a lot to think about. I will freely confess to not always having each of these concepts “top of mind.” Sometimes, audio turns into a pressure situation where both musicians and techs get chased into corners. It can be very hard for a person who’s not on deck to figure out what particular issue is in effect. For folks without a lot of technical experience who play or sing, identifying a problem beyond “something’s not right” can be too much to ask.

In the heat of the moment, it’s probably best to simply remember that yes, monitors are there to be used – but not to be overused. Effective troubleshooting is often centered around taking things out of a misbehaving equation until the equation begins to behave again. So, if you want to unsuckify your monitors, try getting as much out of them as possible. You may be surprised at what actually ends up working just fine.

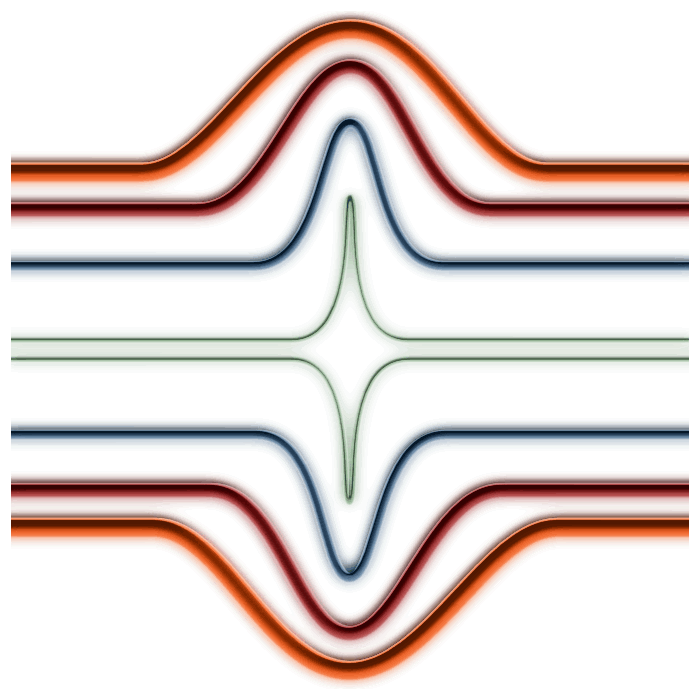

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.