Sometimes, the best way to find something is to be looking for something else entirely.

A couple of weeks ago, I got it into my head to do a bit of testing. I wanted to see how much delay time I could introduce into a monitor feed before I noticed that something was amiss. To that end, I took a mic and monitor that were already set up, routed the mic through the speaker, and inserted a delay (with no internal feedback) on the signal path. I walked between FOH (Front Of House) and the stage, each time adding another millisecond of delay and then talking into the mic.

For several go-arounds, everything was pretty nondescript. I finally got to a delay time that was just noticeable, and then I thought, “What the heck. I should put in something crazy to see how it sounds.” I set the delay time to something like a full second, and then barked a few words into the mic.

That’s when it happened.

First, silence. Then, loud and clear, the delayed version of what I had said.

…and then, the delayed version of the delayed version of what I had just said, but rather more quietly.

“Whoops,” I thought, “I must have accidentally set the delay’s feedback to something audible.” I began walking back to FOH, only to suddenly realize that I hadn’t messed up the delay’s settings at all. I had simply failed to take into account the entire (and I do mean the ENTIRE) signal path I was working on.

Hold that thought.

Back In The Day

There was a time when delay effects weren’t the full-featured devices we’re used to. Whether the unit was using a bit of tape or some digital implementation, you didn’t always get a processor with a knob labeled “feedback,” or “regen,” or “echoes,” or whatever. There was a chance that your delay processor did one thing: It made audio late. Anything else was up to you.

Because of this, certain consoles of the day had a feature on their aux returns that allowed for the signal passing through the return to be “multed” (split), and then sent back through the aux send to the processor it came from. (On SSL consoles, this feature was called “spin.”) You used this to get the multiple echoes we usually associate with delay as an effect for vocals or guitar.

At some point, processor manufacturers decided that including this feature inside the actual box they were selling was a good idea, and we got the “feedback” knob. There’s nothing exotic about the control. It just routes some of the output back to the input. So, if you have a delay set for some number of milliseconds, and send a copy of the output back to the input end (at a reduced level), then you get a repeat every time your chosen number of milliseconds ticks by. Each repeat drops in level by the gain reduction applied at the feedback control…and eventually, the echo signal can’t be readily heard anymore.

But anyway, the key point here is that whether or not it’s handled “internally,” repeating echoes from a delay line are usually caused by some amount of the processor’s output returning to the front end to be processed again. (I say “usually” because it’s entirely possible to conceive of a digital unit that operates by taking an input sample, delaying the sample, playing the sample back at some volume, and then repeats the process for the sample a certain number of times before stopping the process. In this case, the device doesn’t need to listen to its own output to get an echo.)

I digress. Sorry.

If the output were to be routed back to the input at “unity gain,” (with no reduction or increase in level relative to the original output signal) what would happen? That’s right – you’d get an unlimited number of repeats. If the output is routed back to the front end at greater than unity gain, what would happen? Each repeat would grow in level until the processor’s output was completely saturated in a hellacious storm of distorted echo.

Does that remind you of anything?

Acoustical Circuits

This is where my previous sentence comes into play: “I had simply failed to take into account the entire (and I do mean the ENTIRE) signal path I was working on.” I had temporarily forgotten that the delay line I was using for my tests had not magically started to exist in a vacuum, somehow divorced from the acoustical circuit it was attached to. Quite the opposite was true. The feedback setting on the processor might have been set at “negative infinity,” but that did NOT mean that processor output couldn’t return to the input.

It’s just that the output wasn’t returning to the input by a path that was internal to the delay processor.

I’ve talked about acoustical, resonant circuits before. We get feedback in live-audio rigs because, rather like a delay FX unit, our output from the loudspeakers is acoustically routed back to our input microphones. As the level of this re-entrant signal rises towards being equal with the original input, the hottest parts of the signal begin to “smear” and “ring.” If the level of the re-entrant signal reaches “unity,” then the ringing becomes continuous until we do something to reduce the gain. If the returning signal goes beyond unity gain, we get runaway feedback.

This is not fundamentally different from our delay FX unit. The signal output from the PA or monitor speakers takes some non-zero amount of time to get back into the microphone, just like the feedback to the delay takes a non-zero amount of time to return. We’re just not used to thinking of the microphone loop in that way. We don’t consciously set a delay time on the audio re-entering the mic, and we don’t intentionally set an amount of signal that we want to re-enter the capsule – we would, of course, prefer that ZERO signal re-entered the capsule.

And the “delay time” through the mic-loudspeaker loop is just naturally imposed on us. We don’t dial up “x number of milliseconds” on a display, or anything. However long it takes audio to find its way back through the inputs is however long it takes.

Even so, feedback through our mics is basically the same creature as our “hellacious storm” of echoes through a delay processor. The mic just squeals, howls, and bellows because of differences in overall gain at different frequencies. Those frequencies continue to echo – usually, so quickly that we don’t discern individual repeats – while the other frequencies die down. That’s why the fighting of feedback so often involves equalization: If we can selectively reduce the gain of the frequencies that are ringing, we can get their “re-entry level” down to the point where they don’t noticeably ring anymore. The echoes decay so far and so fast that we don’t notice them, and we say that the system has stabilized.

All of this is yet another specific case where the patterns of audio behavior mirror and repeat themselves in places you might not expect.

As it turns out, you can put this to very powerful use.

The Application

As I discussed in “Transdimensional Noodle Baking,” we can do some very interesting things with audio when it comes to manipulating it in time. Making light “late” is a pretty unwieldy thing for people to do, but making audio late is almost trivial in comparison.

And making audio events late, or spreading them out in time, allows you to examine them more carefully.

Now, you might not associate careful examination with fighting feedback issues, but being able to slow things down is a big help when you’re trying to squeeze the maximum gain-before-feedback out of something like a a monitor rig. It’s an especially big help when you’re like me – that is to say, NOT an audio ninja.

What I mean by not being an audio ninja is that I’m really quite poor at identifying frequencies. Those guys who can hear a frequency start to smear a bit, and instantly know which fader to grab on their graphic EQ? That’s not me. As such, I hate graphic EQs and avoid putting them into systems whenever possible. I suppose that I could dive into some ear-training exercises, but I just can’t seem to be bothered. I have other things to do. As such, I have to replace ability with effort and technology.

Now, couple another issue with that. The other issue is that the traditional method of “ringing out” a PA or monitor rig really isn’t that great.

Don’t get me wrong! Your average ringout technique is certainly useful. It’s a LOT better than nothing. Even so, the method is flawed.

The problem with a traditional ringout procedure is that it doesn’t always simulate all the variables that contribute to feedback. You can ring out a mic on deck, walk up, check it, and feel pretty good…right up until the performer asks for “more me,” and you get a high-pitched squeal as you roll the gain up beyond where you had it. The reason you didn’t find that high-pitched squeal during the ringout was because you didn’t have a person with their face parked in front of the mic. Humans are good absorbers, but we’re also partially reflective. Stick a person in front of the mic, and a certain, somewhat greater portion of the monitor’s output gets deflected back into the capsule.

You can definitely test for this problem if you have an assistant, or a remote for the console, but what if you have neither of those things? What if you’ve got some other weird, phantom ring that’s definitely there, and definitely annoying, but hard to pin down? It might be too quiet to easily catch on a regular RTA (Real Time Analyzer), and you might not be able to accurately whistle or sing the tone while standing where you can easily read your RTA. Even if you can carry an RTA with you (if you have a smartphone, you can carry a basic analyzer with you everywhere – for free) you still might not be able to accurately whistle or sing the offending frequency.

But what if you could spread out the ringing into a series of discrete echoes? What if you could visually record and inspect those echoes? You’d have a very powerful tuning tool at your disposal.

The Implementation

I admit, I’m pretty lucky. Everything I need to implement this super-nifty feedback finding tool lives inside my mixing console. For other folks, there’s going to be more “doing” involved. Nevertheless, you really only need to add two key things to your audio setup to have access to all this:

1) A digital delay that can pass all audio frequencies equally, is capable of long (1 second or more) delays, and can be run with no internal feedback.

2) A spectrograph that will show you a range of 10 seconds or more, and will also show you the frequency under a cursor that you can move around to different points of interest.

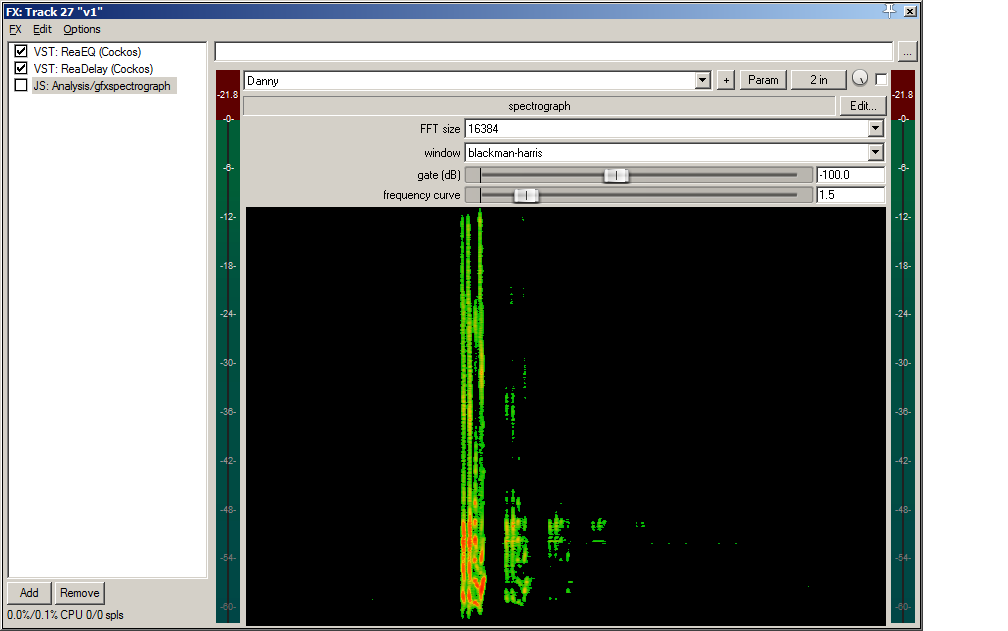

A spectrograph is a type of audio analysis system that is specifically meant to show frequency magnitude over a certain amount of time. This is similar to “waterfall” plots that show spectral decay, but a spectrograph is probably much easier to read for this application.

The delay is inserted in the audio path of the microphone, in such a way that the only signal audible in the path is the output of the delay. The delay time should be set to somewhere around 1.5 to 2 seconds, long enough to speak a complete phrase into the mic. The output of the signal path is otherwise routed to the PA or monitors as normal, and the spectrograph is hooked up so that it can directly (that is, via an electrical connection) “listen” to the signal path you’re testing. The spectrograph should be set up so that ambient noise is too low to be visible on the analysis – otherwise, the output will be harder to interpret.

To start, you apply a “best guess” amount of gain to the mic pre and monitor sends. You’ll need to wait several seconds to see if the system starts to ring out of control, because the delay is making everything “late.” If the system does start to ring, the problem frequencies should be very obvious on the spectrograph. Adjust the appropriate EQs accordingly, or pull the gain back a bit.

With the spectrograph still running, walk up to the mic. Stick your face right up on the mic, and clearly but quickly say, “Check, test, one, two.” (“Check, test, one, two” is a phrase that covers most of the audible frequency spectrum, and has consonant sounds that rely on high-mid and high frequency reproduction to sound good.)

DON’T FREAKIN’ MOVE.

See, what you’re effectively doing is finding the “hot spots” in the sound that’s re-entrant to the microphone, and if you move away from the mic you change where those hot spots are. So…

Stay put and listen. The first thing you’ll hear is the actual, unadulterated signal that went through the microphone and got delivered through the loudspeaker. The repeats you will hear subsequently are what is making it back into the microphone and getting re-amplified. If you hear the repeats getting more and more “odd” and “peaky” sounding, that’s actually good – it means that you’re finding problem areas.

After the echoes have decayed mostly into silence, or are just repeating and repeating with no end in sight, walk back to your spectrograph and freeze the display. If everything is set up correctly, you should be able to to visually identify sounds that are repeating. The really nifty thing is that the problem areas will repeat more times than the non-problem areas. While other frequencies drop off into black (or whatever color is considered “below the scale” by your spectrograph) the ringy frequencies will still be visible.

You can now use the appropriate EQs to pull your problem frequencies down.

Keep iterating the procedure until you feel like you have a decent amount of monitor level. As much as possible, try to run the tests with gains and mix levels set as close to what they’ll be to the show as possible. Lots of open mics going to lots of different places will ring differently than a few mics only going to a single destination each.

Also, make sure to remember to disengage the delay, walk up on deck, and do a “sanity” check to make sure that everything you did was actually helpful.

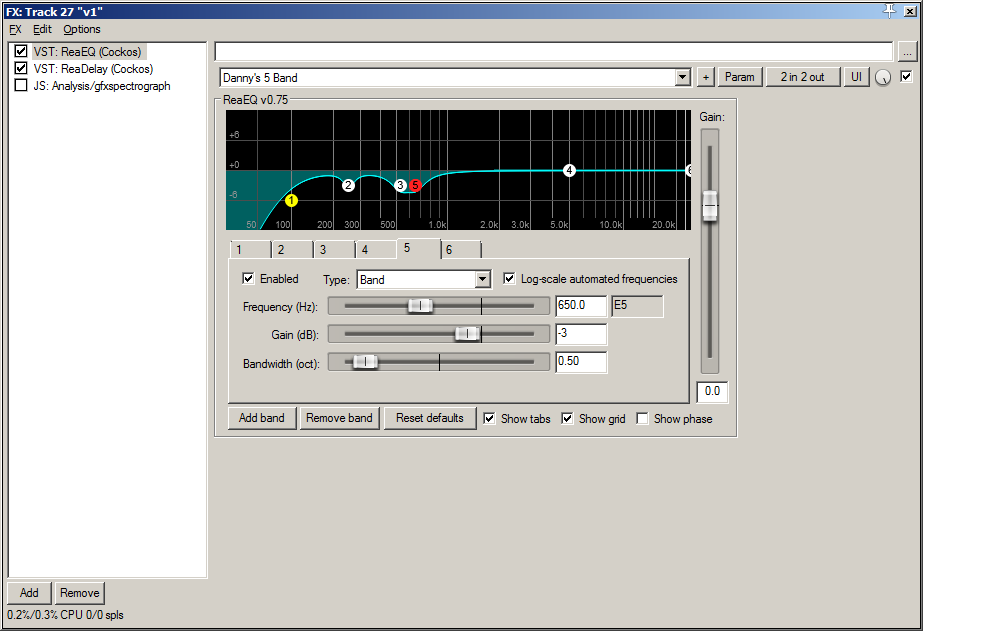

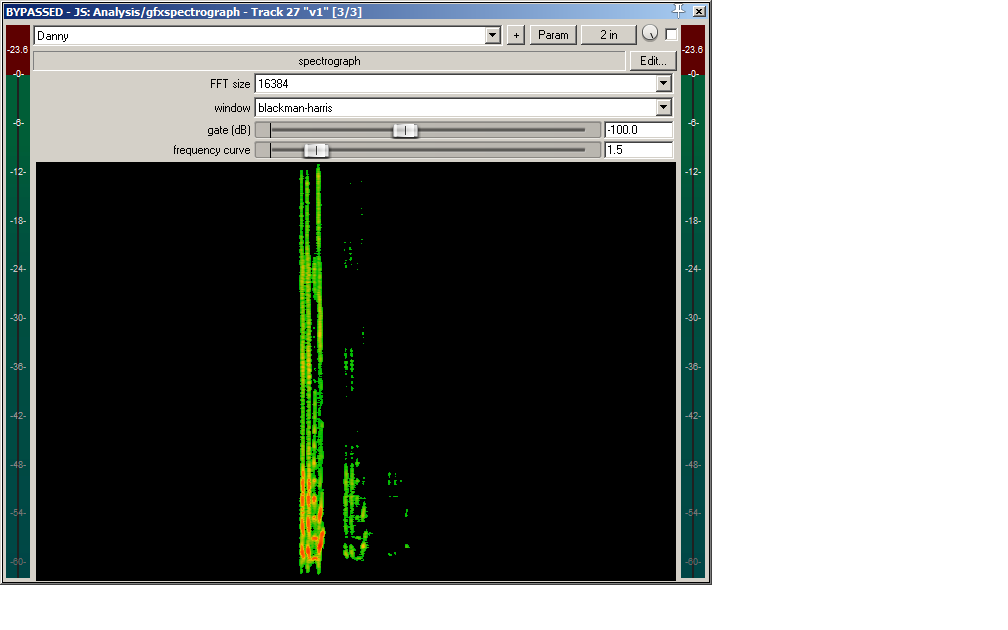

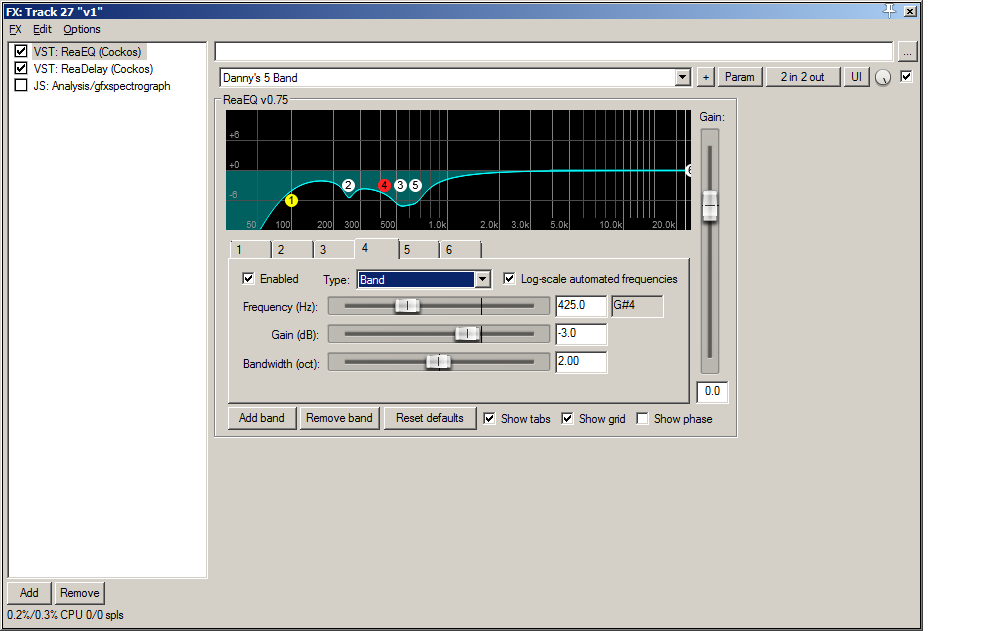

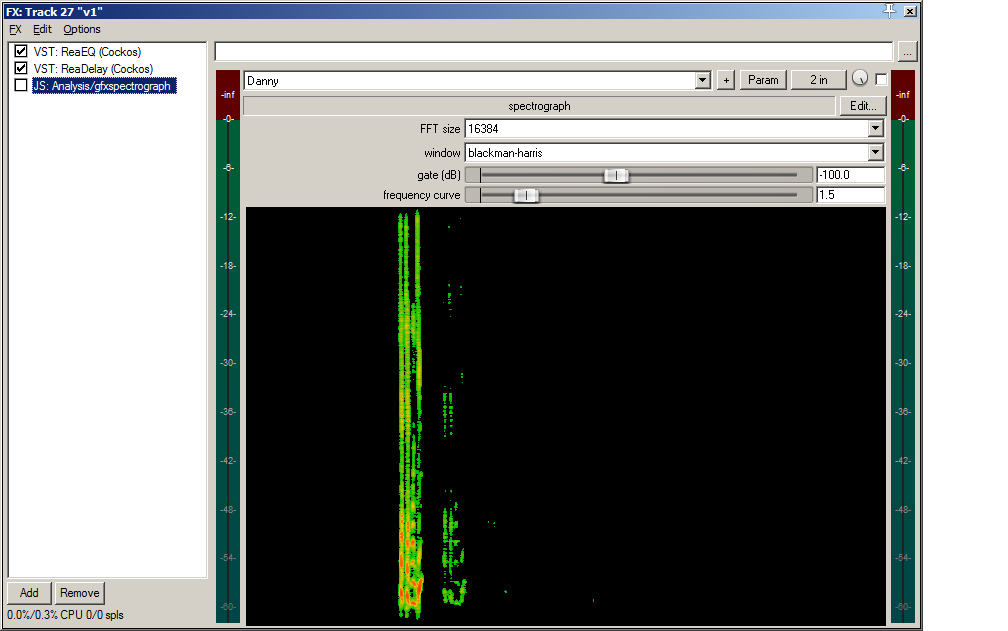

If you’re having trouble visualizing this, here are some screenshots depicting one of my own trips through this process:

This spectrograph reading clearly shows some big problems in the low-mid area.

Some corrective EQ goes in, and I retest.

That’s better, but we’re not quite there.

More EQ.

That seems to have done the trick.

I can certainly recognize that this might be more involved than what some folks are prepared to do. I also have to acknowledge that this doesn’t work very well in a noisy environment.

Even so, turning feedback problems into a series of discrete, easily examined echoes has been quite a revelation for me. You might want to give it a try yourself.

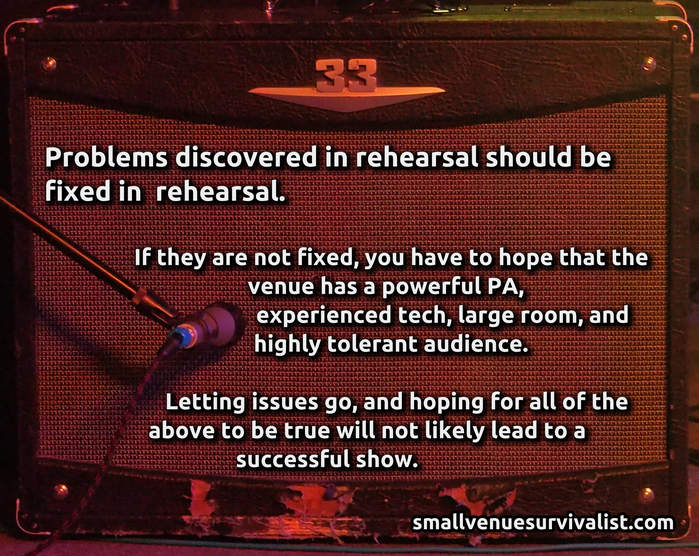

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

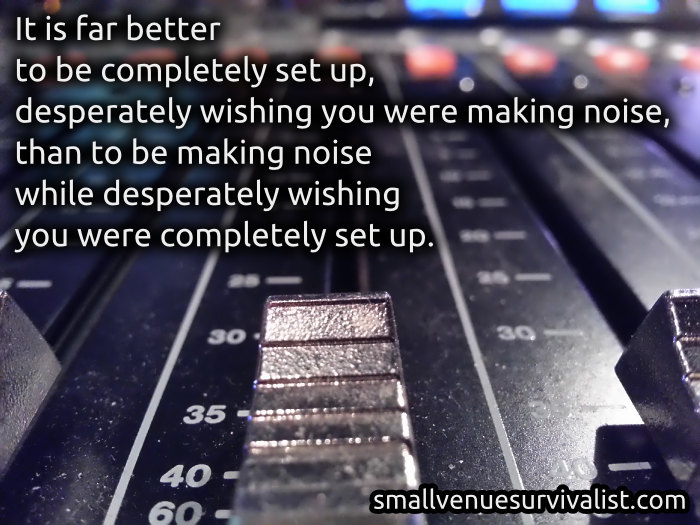

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.