Do what’s actually helpful, and then stop “do-ing.” The show will be just fine.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

I’m told that live-audio is a thankless job. This is news to me, because I’m fortunate enough to be thanked – often – for the work I do.

The problem is that when I receive the most effusive praise, I feel like a fraud. When somebody says, “you made it sound SO GOOD,” I’m pretty sure that credit isn’t really going where it’s due. I can’t clearly remember the last time I took something that sounded bad, and through force of will, turned it into an amazing sonic experience. Mostly, I take bands that already sound good, and then help the couple of things that can’t help themselves to be in quite the right place.

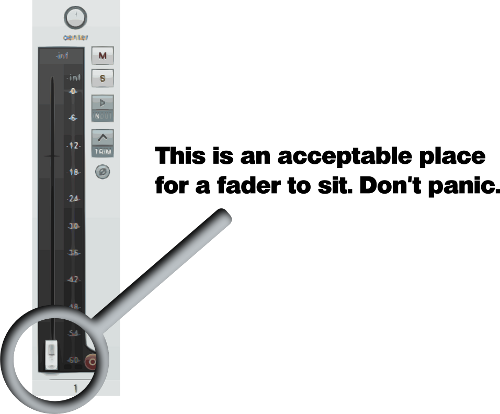

The more time I spend working in small rooms, the more it seems to me that at least 50% – 75% of my job is staying out of the way of the band. Functionally, what this means is that a lot of my faders sit at either the actual “negative infinity” point, or at a functional negative infinity (that is, the fader is set at a level where the contribution from the PA is not readily perceptible).

Because of the popular perception of what an audio human is supposed to do, the desirability of having a number of channels “doing nothing” is counter-intuitive. I’m pretty comfortable with it as a concept, and even I will go through periods where I get out of discipline.

But it works beautifully.

If You Don’t Need To Be On Deck, Don’t Be On Deck

That heading up there is one of the phrases that stage crews learn. It’s also pretty easy to grasp at a physical level. At some point, it’s easy to see that chewing up space on stage while contributing nothing to the show is a bad idea. You’re very likely to impede the progress of someone who actually needs to, you know, get stuff done. If you’re impeding the progress of someone with a job to do, you’re very likely to hear the words “Get out of the !@#$ing way!”

The issue for the audio human standing behind the console is that the line between “helpful contribution” and “just taking up space” isn’t clearly marked. Audio is a really subjective sort of business, and a lot of what audio humans do involves end results that aren’t easily measured in an objective way. The overall problem is exacerbated because of the mistaken belief that the most important work in audio engineering for entertainment is done with mixing consoles and rack gear. It isn’t – but that’s probably a whole other article.

With work at show control being the object of worship, the audio human can feel a lot of pressure to “make magic happen” with the tools that are seen as being most important. Especially because live-audio is an additive affair – where the sound of the PA combines with the sound from the stage – this need to appear productive can lead to three, generalized, “bad sound” scenarios:

1) The band’s sound is tossed out in favor of the engineer getting his or her sound, with questionable results.

2) The show is very, very loud, with questionable tolerability.

3) A combination of both.

Trying To Fix Everything

There’s a hilarious Xtranormal video floating around that illustrates scenario #1. In it, a jazz drummer is up against an audio dude. In complete deadpan, dialogue in this overall vein is uttered:

“We need to cut a hole in your kick drum.”

“This is a jazz kit. It uses special, very expensive heads. We are not cutting a hole in anything.”

“But, dude, how will I get my sound if we don’t cut a hole in the front of the kick?”

The third line is the crux of the whole thing. Getting what is perceived to be the most impressive kick sound – from the tech’s perspective – has become such a priority that the audio human is blind to what they’re actually dealing with. The need to be looked upon as a wizard with a console and outboard processing is so great that the tech is ready to turn a jazz act into a rock band, and to do so by wrecking an instrument.

When this need to fix everything generalizes into a whole-band situation, you can very quickly cross into the territory where the band no longer sounds like itself. Instead, you get the tech’s best effort at a huge snare, massive kick, elephantine toms, roaringly thick guitars, thundering bass, and “radio announcer” vocals…all blended into a result that sounds like a completely different band playing another band’s songs. Usually, the overall sound is that of the audio human’s favorite genre, and so the tech gets away with this behavior as long as the band is in that general area of music. When the band is significantly different, though, people walk away saying, “It just didn’t sound right,” without necessarily knowing why. If something about the band prevents the tech from achieving “the right sound,” the audio human is apt to complain that the band was hard to work with.

Luckily, the medicine for this condition is cheap, and easily available: Get out of the effing way! It’s amazing how adopting the attitude of “it’s about getting the band’s sound in the room, and not my own sound” can simplify your life. It’s amazing how much less agonizing you have to do when you don’t need to do microsurgery on every input’s frequency response and dynamic range. It’s amazing how fluid, simple, and enjoyable a show can be when every second of it doesn’t have to be managed.

It’s also amazing how, when you stop trying to fix everything, you don’t have to throw so much money at more and different gear.

The Show Sounds Huge, But Everybody Left

The #2 and #3 scenarios often result from trying to fix everything. As I mentioned earlier, this is because sound reinforcement is an additive exercise.

Live-sound engineer and gear retailer Mark Hellinger really nailed it when he stated a particular belief of his: Audio techs don’t feel like they’re really in control of the show until the PA is 10 dB ahead of everything else.

This anecdotally supported belief dovetails nicely with quantitative observations of SPL (Sound Pressure Level) addition. If you add the SPLs of two sound sources, where one source is observed to be 10 dB more intense than the other, the result will be the SPL of the louder source plus about 0.4 dB. The loud source pretty much wipes out the quieter sound.

So…

As the “I have to fix everything!” audio tech goes about getting their sound, they have to overcome the sound of the band in the room. The amount of SPL that a band can produce, even without a PA, can be rather surprising. (If you ever want a quick and unmerciful education in this, work with a band that switches from an acoustic drumkit to an electronic drumkit. You will be shocked at just how hard you have to drive the PA to make the e-kit fit in the same SPL “box” as the acoustic drums. I speak from experience.) A full-tilt band – even a fairly reasonable one – in a small venue can be a pretty loud experience. If the audio human just has to override the band’s sound with his or her own sound, “pretty loud” has probably just had anywhere from 6 – 12 dB of continuous SPL added on.

In a small space, this can mean that the engineer’s mad rush to fix everything creates a mad rush for the exits. A tech’s incorrect prioritization can clear a room just as much as a musician’s myopia can do the same thing.

As with trying to fix everything, getting out of the effing way can keep more people in the venue. When the goal becomes working WITH the sound of the band in the room, instead of against it, you have a much better shot at keeping within an audience’s reasonable SPL range. (No guarantees, of course. This is a subjective business.)

Going against the flow of a band’s sound is difficult, loud, and requires a ton of work. Getting out of the way and swimming with the current is much easier, much quieter, and a lot less tiring. It can be hard to discipline yourself to work this way (I still get things very wrong in certain situations), especially since not getting “your sound” fails to feed your ego (please refer to the previous parenthetical statement).

But I’ll be doggone if getting out of the effing way hasn’t proven itself to be very effective.

The big, red note is what musicians think they’re getting paid for. Actually, most musical acts are paid for their ability to bring out the people in the foreground.

The big, red note is what musicians think they’re getting paid for. Actually, most musical acts are paid for their ability to bring out the people in the foreground.