A while back, a friend paid me a compliment. She said that she would love to bring me out to where her ballet company performs, so that I could assist with the audio. She was sure it would be a great show.

(Thanks, Gina! I definitely think it would be cool to work with Ballet Ariel.)

One day, I was in desperate need of a project to do, and I hit upon the idea of melding a full-tilt, Rock and Roll presentation of Pink Floyd’s “The Wall” with a similarly full-tilt, dramatic interpretation of the story through ballet.

In the end, I couldn’t quite get the results I wanted by just using “The Wall,” so I pulled in other Pink Floyd songs to introduce themes that would motivate the characters in ways I found interesting. I’m still basically ripping off “The Wall” as it was presenting in cinematic form, just with certain tweaks and a different ending.

Here’s what I ended up with. My guess is that the show could be pulled off for about $250,000 – anybody have any rich uncles who love Pink Floyd?

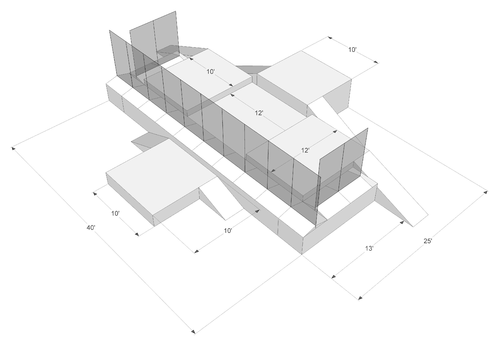

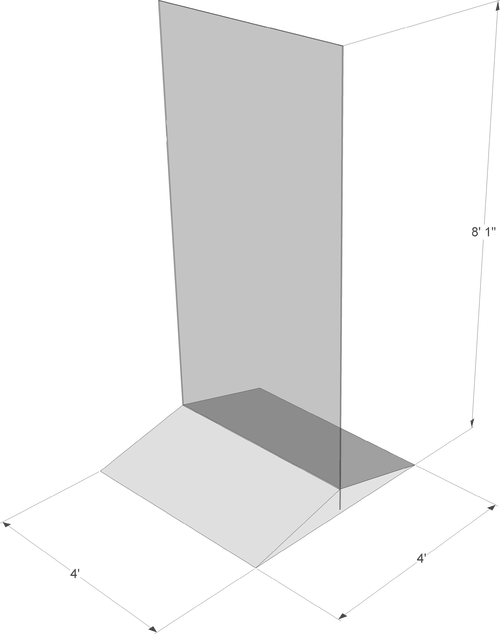

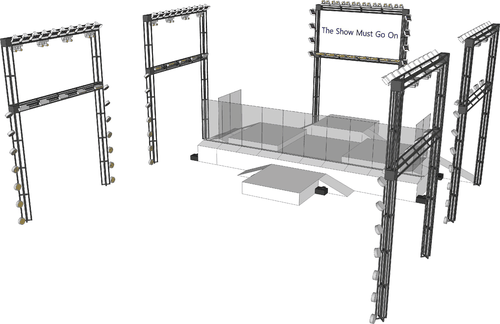

The Set

The idea for the set is to have a raised area for “Pink” and “Floyd” to perform, which is backed by a large platform for the band. The band area is roughly halfway enclosed by plexiglass sound barriers, which keep the band mostly visible while reducing their stagevolume’s contribution to sound in the house.

It is critical that the stage be well braced. Resonance from the platforms could be a huge sonic problem otherwise. The band portion of the stage should be carpeted, to help absorb sound.

The cost to construct the stage will probably be around $10,000.

The thumbnails below link to full-size versions of the pictures.

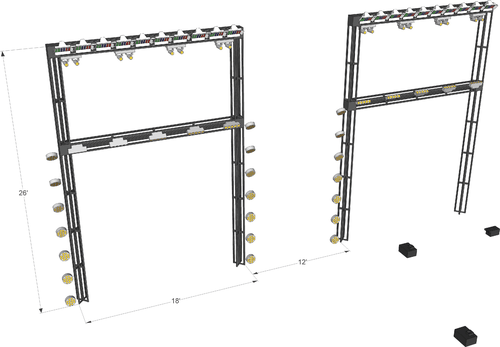

The Lighting Rig

The lighting rig is a huge piece of the show’s “soul,” and is also the show’s largest technological element. It is meant to be a primary driver of the show’s emotion and pacing, at a level equal to the physical movement by the performers and the music provided by the band.

A certain amount of restraint will be necessary, because the temptation will probably be to overuse the rig. We do want it to do some exciting things, and to do those things fairly frequently – but not so frequently that the audience simply filters the light show from their mind.

The experiment inherent in the rig is that there is no traditional front-lighting. Everything is from the side and/ or above. This is something of a risk, but the risk can be mitigated by performing the show in a space where front-lighting is already installed. The key luminaires, FX devices, rigging, and video gear are as follows:

- 2 Haze Generators

- 4 Geyser RGB Fog FX Units

- 42 SlimPAR 12 IRC Sidelights

- 48 SlimBANK Over-side lights

- 28 BeamBAR Beam FX Units

- 24 Intimidator Duo Moving Heads

- 1 Rear projection screen

- 1 5000+ ANSI lumen projector

- 95 4′ sections of Featherlite Truss

- 20 Featherlite square truss connectors

These pieces, along with their associated control gear, cabling, and miscellaneous items, are estimated to cost $67,000.

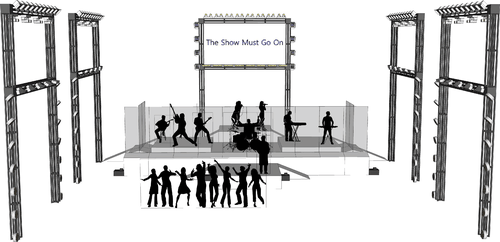

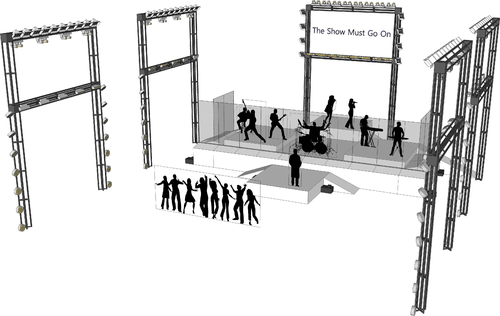

The Complete Stage, With Figures For Scale

The FOH Audio Rig

Like the lighting rig, the audio system needs to be extensive enough to be “big,” but the temptation to overuse it will have to be resisted. To that end, it seems reasonable to set a goal of having 50% of the audience experience an average level of no more than 100 dB SPLZ, slow. (Ideally, 94 dB SPLZ, slow would be the upper limit.)

Specifics in terms of the audio rig are not as important as those of the lighting rig. Many different kinds of subwoofer could be suitable, for example. In general, the audio system should include:

- 8, 18-inch subwoofers

- 8, 15-inch subwoofers

- 8, 15-inch LF full-range enclosures, biamped, for the main stacks.

- 8, 12-inch LF full range enclosures, biamped, for the main stacks.

- 4, 15-inch LF full range enclosures, single amped, for surround FX.

- 10, 12 inch LF full range enclosures, single amped, for various fills.

This FOH audio rig, along with its associated control and processing gear, could be built at a low-end cost of $25,000. The high end cost, of course, is unlimited. The cost does increase considerable when a monitor rig, mics, and accessories are added, but these have been left out for brevity.

The Cast

The overall imperative for any cast member is to be able, and indeed, delighted, to perform in a “full-tilt rock and roll” show with a live band, atmospheric effects like haze and fog, as well as lights that move and change rapidly at times.

Floyd: The main character.

It’s absolutely imperative that Floyd be VERY strong at duet and solo work, and also able to emote in ways that will seem very concrete and natural to the audience.

Mother: Floyd’s Mom

She will need to be a good soloist, but even more important is her ability to work well in a duet. Like Floyd, she needs to be able to project emotions in a very obvious and relatable way.

Daddy: Floyd’s Dad

The most important thing for this cast member is his ability to act in a vaguely menacing (but still palpably unsettling) way towards Floyd in several scenes. He only ever appears as a ghost. Some competence as a soloist and in duets will be required, but deep experience is probably not necessary – unless the choreographer decides to create some technically challenging moments for him, of course.

Pink: Floyd’s best friend.

He mostly needs to be able to be convincing as a young person who is “partners in crime” with Floyd. However, there is one key moment, late in the show, where he will need to deliver on some key emotions as a ghost. This may be a good part for a dancer who is just ready to transition into duets and solos.

The Groupies: Two “hangers-on” who get close to Floyd and Pink, briefly.

Both will need to be able to project an obvious (but NOT overdone) sort of “average intelligence rock girlfriend” persona. The twist is that, in one scene, they must be able to project a marked prowess as they dance, sensually, with Floyd and Pink. The Groupie who ends up with Floyd will need just that much more emotional ability than The Groupie who ends up with Pink.

The Company: Everybody else. Certain characters may be drawn from the company pool, if necessary.

The company plays concert goers, teachers, schoolkids, regular folks, and so on. The cast members who are the strongest technical and emotional performers should be selected to fill the roles of Pink and Floyd’s teacher, the “undesirables” singled out during In The Flesh, and so on.

The Show

Note: This section is not consistent in terms of details. The really important things are

specified, but there is quite a bit that will have to be determined later.

The audience is seated with the main curtain down. House-light flashes and aural tones should signal 5 minutes, 2 minutes, and 1 minute to show.

The show actually begins with the house-lights up. This is to promote safety for The Company, because they enter through the house. As they walk through the audience seating, they should chatter excitedly about being able to get into the “Pink and Floyd Concert,” amongst other things.

The house-lights dim slowly. The Company should offer the appropriate banter like, “Oh, wow!” and “It’s starting!”

The house goes black, as completely black as possible without compromising safety. The Company goes silent.

After a few seconds…

Prologue – In The Flesh?

The stage explodes with color, light, and sound. Pink and Floyd have started their show. The Company goes wild (silently, as they’re now in full “dance” mode) and go up to the stage to give their rapt attention to Floyd.

[Important – after this point, unless otherwise stated, all cast members are always silent. References to saying things, shouting, narration, etc, are to be mimed or danced and not actually vocalized.]

Although what Floyd sings might be a little confusing, lyrically, The Company is completely enthralled and joyful.

At the ending and plane crash, The Company erupts in celebration…and then freezes at the climax of light and sound.

The screen reads: “Bomber Shot Down – Crew Missing, Presumed Dead”

The Thin Ice

Daddy, as a ghost, stands a bit upstage. Downstage, Mother comforts Floyd, “singing” the song to him.

The Company “ice skates” around Mother and Floyd. When the music rises, Floyd tries to move away from Mother and interact with the “skaters,” but Mother, frightened, clings to him.

Another Brick In The Wall, Part 1

Mother and The Company exit the stage. Floyd attempts to reach Daddy, but he keeps retreating from Floyd’s touch.

The Happiest Days Of Our Lives

The screen reads: “School begins at 8:00 sharp! Tardiness will not be tolerated.”

Floyd finds Pink, and they “go hide” somewhere to have an illicit smoke. They are of course, found by their teacher, who “shouts” at them to “STAND STILL LADDIE!”

The teacher catches Pink, but Floyd gets away and comes downstage to “narrate” to the audience.

As the music rises, The Company (some as teachers, some as students) enter.

Another Brick In The Wall, Part 2

This entire scene is Pink, Floyd, and the students having a passive-aggressive battle. The teachers should turn their backs to give the students the opprotunity to “shout.” (“HEY TEACHER! LEAVE THEM KIDS ALONE!”) The students should be just barely restrained when the teachers are looking at them.

As the scene closes, Floyd goes home and goes to bed. There is silence. Floyd falls asleep, and then Daddy appears as a ghost.

Floyd jolts upright.

Welcome To The Machine

Daddy shows Floyd a vision of a possible future life. In this life, everyone has been “good girls and boys,” and are now productive (but somewhat lifeless) workers in a factory. The work is boring and mechanical.

The screen reads: “Work begins at 8:00 sharp. Late arrivals must be pre-approved with form 86-T, and you must contact your supervisor, undersupervisor, and supersupervisor three weeks in advance.”

There are blasts of steam (actually fog) throughout the scene.

As Daddy “talks” to Floyd, he should whisper in his ears, move around him in an almost predatory fashion, and invade Floyd’s personal space often. However, at no point should Daddy and Floyd actually touch.

There should be a sense of mounting horror (on Floyd’s part) at the prospect of being put to work in the factory.

Time

Suddenly, the clocks strike. Horrified, Floyd watches as the factory workers fall over, lifeless.

The factory workers slowly rise, and help Daddy by acting out his “narration” of the song. At first, they move as carefree youths, but then seem to panic as the guitar solo comes in. An unseen terror is chasing them.

At the mention of the sun, they run out of energy and start collapsing. Less and less able to move. They seem to be dying off. Things seem to be falling out of their hands.

As the song ends, Daddy walks away.

Mother

Floyd wakes up, and finds his mother for support.

Mother tries to reassure Floyd. At first she seems successful, but as her parts of the song progress, it’s made clear that all she’s capable of is clinging to Floyd, preventing him from getting out of her sight.

At the end of the song, Floyd becomes abruptly repulsed. He runs off.

On The Run

Mother pursues Floyd, but can’t seem to catch up to him. Floyd links up with Pink, and they start to “write songs,” and “play shows” to The Company. Whenever Mother gets close, Pink, Floyd, and The Company always move on, looking cheery.

At the “boom,” the screen reads: “Pink and Floyd Song a Smash Hit!” The foggers let out a large, sustained blast.

Learning To Fly

Pink and Floyd perform their hit song to their adoring fans (The Company). Floyd seems free and happy, and The Company is ecstatic. The only one not seeming to enjoy things is Mother, who is unintentionally overwhelmed by the crowd and unable to get close to her son. She is essentially invisible to everyone.

(Mother’s part shouldn’t be too big in this scene – it has a dampening effect on the emotional tone, and this scene is meant to be one of the few really happy ones.)

Have A Cigar

The screen reads: “Pink and Floyd Continue Topping The Charts!”

Pink and Floyd are being wined, dined, congratulated, back-slapped, and buttered up by The Company as recording industry execs. In terms of formation, there are three areas:

The center, where Pink and Floyd spend most of their time.

The inner circle, where the execs are fawning over Pink and Floyd.

The outer circle, where the execs “talk” amongst themselves, count their money, and anticipate a very profitable future.

At the end of the scene, Pink and Floyd walk off, and are met by The Groupies.

Money

Pink and Floyd take The Groupies out for a night of partying. This scene should be very unambiguously about conspicuous consumption, and (at least) heavily imply that the characters fall into using alcohol and hard drugs. These are young people caught up in an imaginary-yet-real world where they can have anything they want. Pink should be noticeably more affected by his drinking and drug use than Floyd. The Groupies mostly act as starry-eyed hangers-on.

Young Lust

The screen reads: “Pink and Floyd – Are These The Girlfriends? Exclusive Photos Inside!”

The Groupies definitely want to hang on to Pink and Floyd, and so now they reveal their true prowess – sensuality. This scene should provide a great opportunity for The Groupies to show off movement that is an order of magnitude more fluid and technically impressive than what they’ve done before.

At the guitar solo, Pink and his Groupie run off, leaving Floyd and his Groupie to do a short, but intense duet.

At the end of the scene, the song ends and silence falls. Suddenly, the phone rings. Floyd picks is up, and reacts with disbelief, then shock and grief. He and his Groupie exit.

The screen reads: “Pink Dead in Auto Accident. Substance Abuse a Factor?”

The Great Gig In The Sky

Pink starts out bewildered. The Groupie is lying lifeless nearby. As the vocal part comes in, The Company enters as angels. They “wake” The Groupie, and escort both her and Pink to heaven. They both look apprehensive as they arrive, but it’s soon clear that they’re both pardoned. They go off happily, trailed by The Company.

Wish You Were Here

Floyd is alone and dejected. All he has to express is his grief in a lengthy solo. He is alternately lit dimly and in silhouette.

At the end of the song, Floyd sits down and switches on a TV. He becomes cold and distant.

One Of My Turns

The Groupie enters, and, oblivious to Floyd’s feelings at the start, does her routine of being fantastically impressed by the house. She tries to get Floyd’s attention, but becomes crestfallen as all her strategies fail.

Floyd begins his part in a self-absorbed way, seemingly oblivious to The Groupie. However, as the song’s intensity rises. He begins interacting with her.

The key thing for this part is that The Groupie does feel threatened by Floyd, but not in the same way as Floyd was threatened by Daddy earlier. Floyd is not a creeping, psychological menace. In fact, he doesn’t mean to threaten her at all – he’s dangerous because he’s suddenly gone manic.

At the end of the scene, The Groupie runs off in terror.

Don’t Leave Me Now

Floyd is now alone, and not by choice. The Company enters, but stands in a semi-circle upstage, their backs turned to Floyd.

At the guitar solo, The Company suddenly turns and tries to get Floyd’s attention. They are now fans, people who desperately want attention from the semi-mythical figure they’ve constructed for themselves.

At the end of the scene, Floyd becomes enraged.

Another Brick In The Wall, Part 3

Floyd angrily chases The Company away, rejecting everyone and everything. He is, briefly a very intentional menace.

Goodbye Cruel World

Floyd, with very muted movement, expresses his alienation.

Sorrow

Floyd spends this entire scene down center, brightly lit, with his head down. He moves very little throughout the lengthy song.

In turns, everyone who Floyd has hurt enters and “has their say.” Mother first, then The Groupie, then members of The Company as fans.

Daddy enters as a ghost, and moves close to Floyd accusingly. Pink also enters as a ghost, and is clearly unhappy with what’s going on. It should be clear that he’s not really upset with Floyd. Concerned would be more accurate.

Near the end of the scene, one or two members of The Company (as recording execs) come on stage and force Floyd to his feet. They are demanding that he keep playing.

The screen reads: “Can The Show Go On?”

In The Flesh

Floyd is still alienated, but gets onstage to do the show. The fans are less animated this time. They’re even a little confused – especially as Floyd says “Pink isn’t well, he’s stayed back at the hotel.” (Pink is very, unambiguously dead, and they know it – but Floyd is in denial. If this can’t be readily expressed through movement, that’s fine. Sometimes a few unanswered questions in an audiences mind are perfectly acceptable.)

As Floyd starts suggesting that people who don’t fit be put “up against the wall,” the fans very quickly (and frighteningly) go along with him. They reject, threaten, and throw out anyone that Floyd points out.

At the climax of the song (which is the end), Floyd runs off by himself. He doses himself with drugs, and falls asleep in the silence.

Two Suns In The Sunset

Pink enters as a ghost. He presents Floyd with a vision of the future, much like Daddy did. In this future, the UK is destroyed in a nuclear attack. Pink is much more sympathetic than Daddy, although Floyd is a little frightened of him.

Although the presentation of this piece is concrete, the intention is that the nuclear attack is a metaphor for the self-destructive behavior that Pink and Floyd have engaged in. The trouble is that expressing a complex and non-concrete concept like that is probably impossible, so we just have to leave things ambiguous.

Comfortably Numb

The screen reads: “The Show Must Go On”

In the silence, Floyd wakes up. He doses himself again, and then, in a daze, goes onstage to do a show.

The Company enters as fans. They are facing Floyd, and interact with him, but they are strangely distant and move slowly. Pink and Daddy enter as ghosts and observe. Daddy is disapproving. Pink is worried.

Near the end, Mother enters. She has finally found Floyd, and manages to get close. As the song ends, in the silence, Floyd waits for the crowd’s adulation. However, he hasn’t done what they want. They become angry, and try to get their hands on him. Daddy is egging them on.

Run Like Hell

Floyd is now the target of The Company. Daddy chases Pink away. Mother is pushed down and out of the way. Floyd’s star has now fallen completely, and the crowd wants vengeance.

Floyd is finally cornered, and roughly pulled to center stage.

The Trial

Daddy stands up-center. The Company enters and flanks him. They join hands, and “speak” with one voice during the trial, becoming a composite character. They slowly close in on Floyd.

The final pronouncement of the court belongs to Daddy. He suddenly separates from The Company and gets right in Floyd’s face. At the order to “Tear down the wall!” The Company sets upon Floyd.

There are flashes as the explosion sounds.

Outside The Wall

As the lights come up we see Floyd cowering. Downstage, we see Mother, who has fallen. Daddy’s ghost enters, and angrily tries to get his hands on Floyd. Before he can get there, though, Pink’s ghost heads him off. Pink gently beckons to Daddy, and they move upstage right.

The Groupie enters, and tries to help Mother to her feet. Floyd looks up and sees them. He approaches, and takes their hands.

A change comes over Daddy, and he follows Pink into a strong light coming from offstage up-right.

Fade to blackout.

Bows

The band begins playing an instrumental version of “In The Flesh?” They vamp the middle part as necessary to extend the piece.

If at all possible, each member of the cast should be given the opportunity to bow as an individual. After the cast has finished, they part to allow a good look at the band, who takes their bow by way of playing the ending to the song.

Immediate blackout – main curtain, house lights.