Sure, it’s a cool toy – but can you make money on it?

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

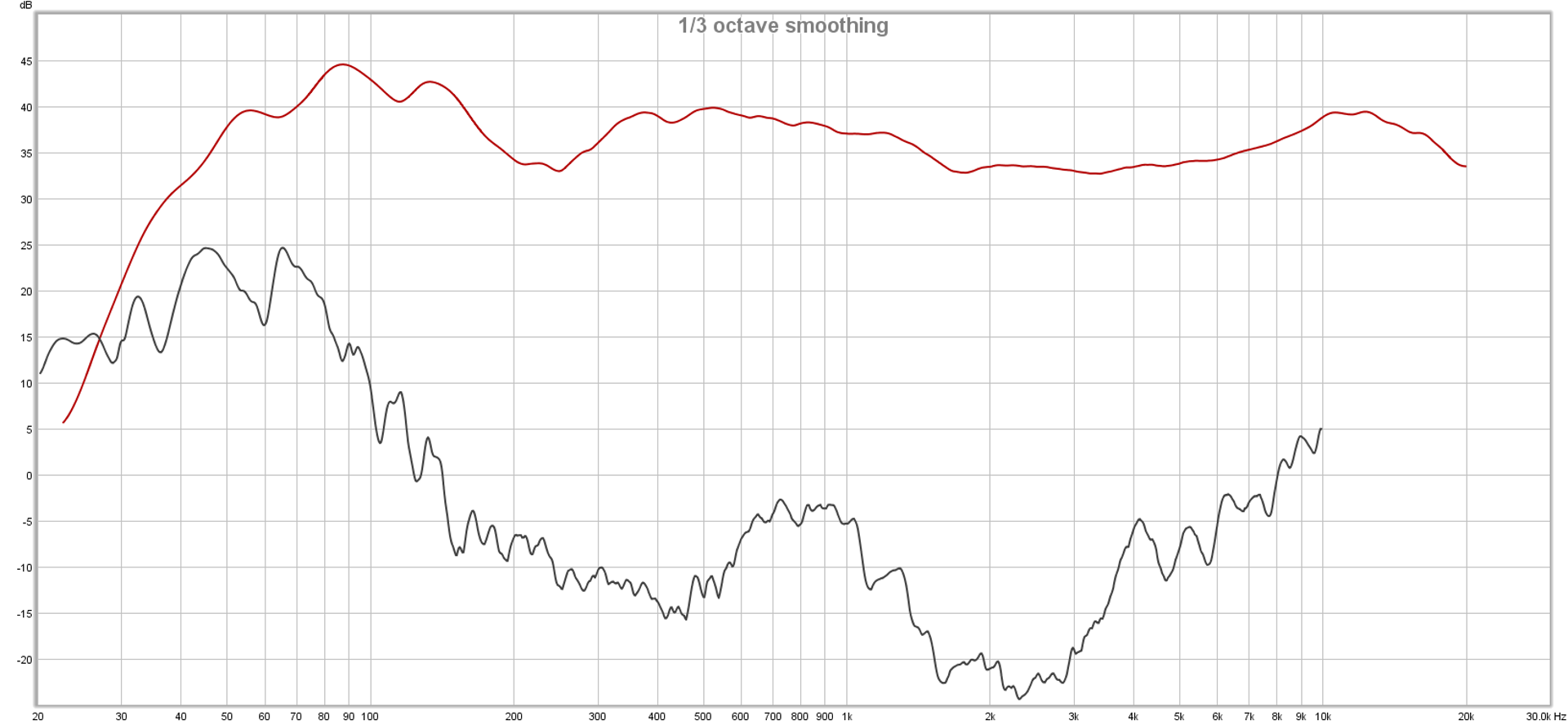

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.If you want to hear great wisdom about the business of sound and music, you should seek out Tim McCulloch over at Pro Sound Web. Just recently he was advising another audio human to “get very real” with a band about demanding a certain console for a tour. Having gotten the strong whiff that the choice of mixing desk was basically one of vanity, Mr. McCulloch dropped the proverbial load of bricks: The gear you take on tour is – and should be categorized as – an expense. The merch and tickets you can sell are profit. (So, decide if you want to make a profit and then act accordingly.)

Of course, the application of this to band tour-o-nomics is self explanatory. With just a bit of imagination, though, you can see how this applies everywhere – especially to audio craftspersons who own equipment.

The gear you own is an expense. It’s always an expense. It’s an expense when you make a full or partial payment for purchase. It’s a debit if you’re making leasing payments. It’s a negative ledger entry every second of every day, because its value depreciates forever in an asymptotic slide towards $0. It’s also a constant drain because you are always paying to store, maintain, and replace it (even if you don’t see a bill directly).

The above is a big reason behind why Tim McCulloch will also tell you that “Excess capacity is infinitely expensive.”

Anyway.

Equipment does not represent profit. It’s a tool that can be used to generate profit, but if you want to imagine the audio business as an airplane, gear is a constant contributor to weight and drag. What you need to keep going is lift and propulsion – profit, that is. Receipts. Money coming in. As such, every purchase and upgrade plan has to answer one question: “How will this increase my receipts?”

The harsh truth is that, past a certain point, just being able to get louder probably won’t increase your receipts.

Past a certain point, being able to rattle peoples’ rib cages with bass probably won’t increase your receipts.

Past a certain point, “super-trick,” spendy mics probably won’t increase your receipts.

A nifty new console probably won’t increase your receipts (not by itself).

What many of us (including myself) have a longstanding struggle with understanding is that what we THINK is cool is not necessarily what gets us phone calls. Meeting the demands of the market is what gets the phone calls. For those of us with maverick-esque tendencies (like Yours “Anti Establishment Is Where It’s At” Truly), we have to take care. We have to balance our curiosity and experimental bent with still being functional where it counts.

We CAN be bold. In fact, I think we MUST be bold. We ought to dare to be different, but we can’t be reckless or vain. If we’re in a situation where our clientele encourages our unorthodoxy, we can let ‘er rip! If not, then we have to accept that going down some particular road might just be for our own enjoyment, and that we can’t bet our entire future on it.

By way of example, I can speak of my own career. I’m currently looking at what the next phase might be like. I have a whole host of notions about what upgrade and expansion paths that might entail. I’ve also gotten on the call list of a local audio provider that I really, really enjoy working with – and the provider in question is far, FAR better than I am at scaring up work. With that being the case, some of my pet-project ideas are going to need a hard look. In devising my upgrade path, it’s far smarter for me to talk to the other provider and find out what would dovetail nicely with their future roadmap, rather than to just do whatever I think might be interesting. Fitting in with them means a chance at more receipts. More receipts means I can do more of what I love. Doing more of what I love means that I might just have enough excess capital to do some weird experiments here and there.

I don’t say any of this to dampen anyone’s enthusiasm. I say this so that we can all be clear about our choices. There are times when we might declare, “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!” It’s just that we sometimes say that without realizing that we’ve said it, in terms of business decisions. If we’re going to buy tools to make money with, it’s a very good idea to figure out what tools will actually serve to make money.