We need to be more clear with each other about what it takes to do things the right way.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

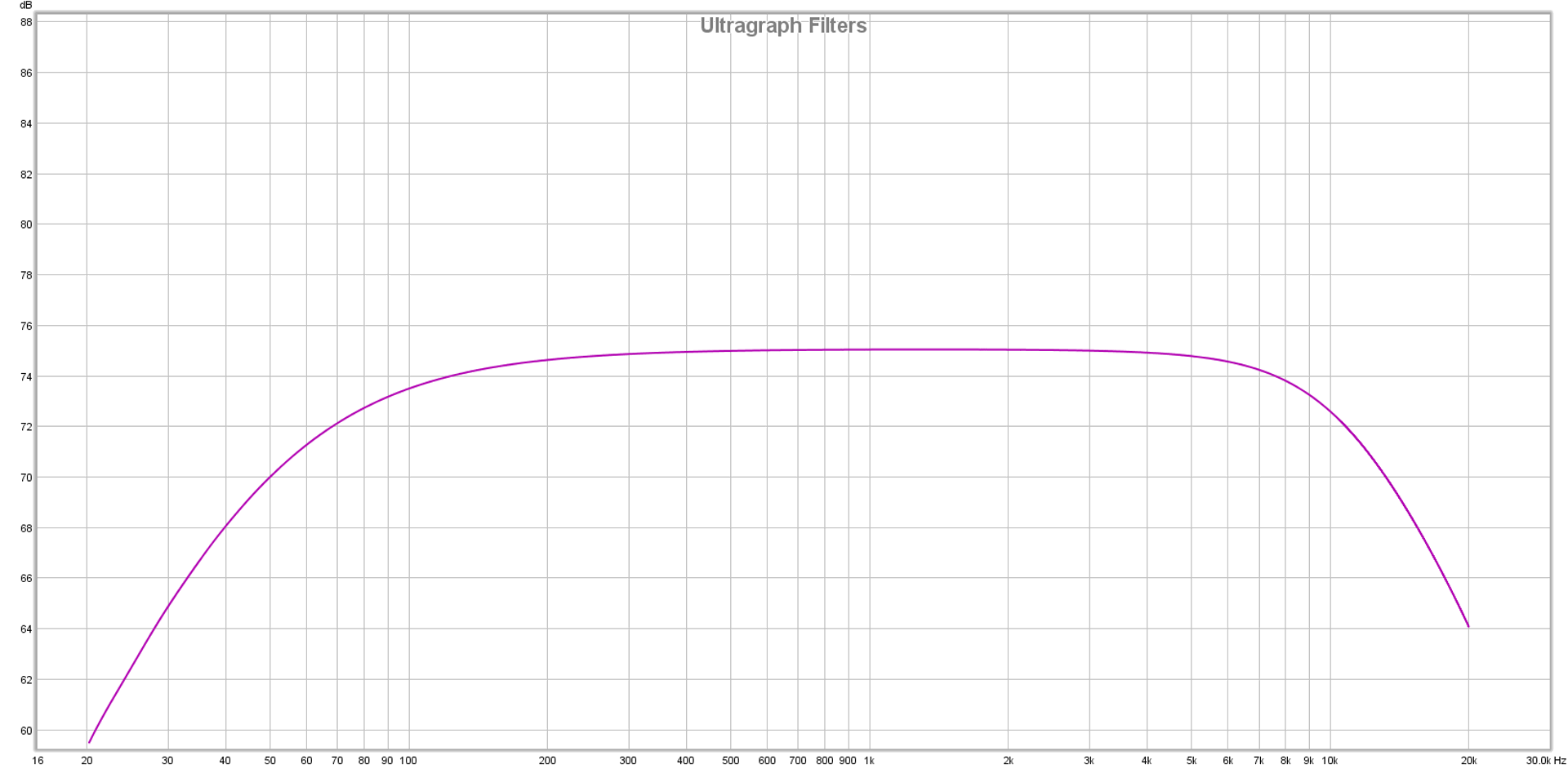

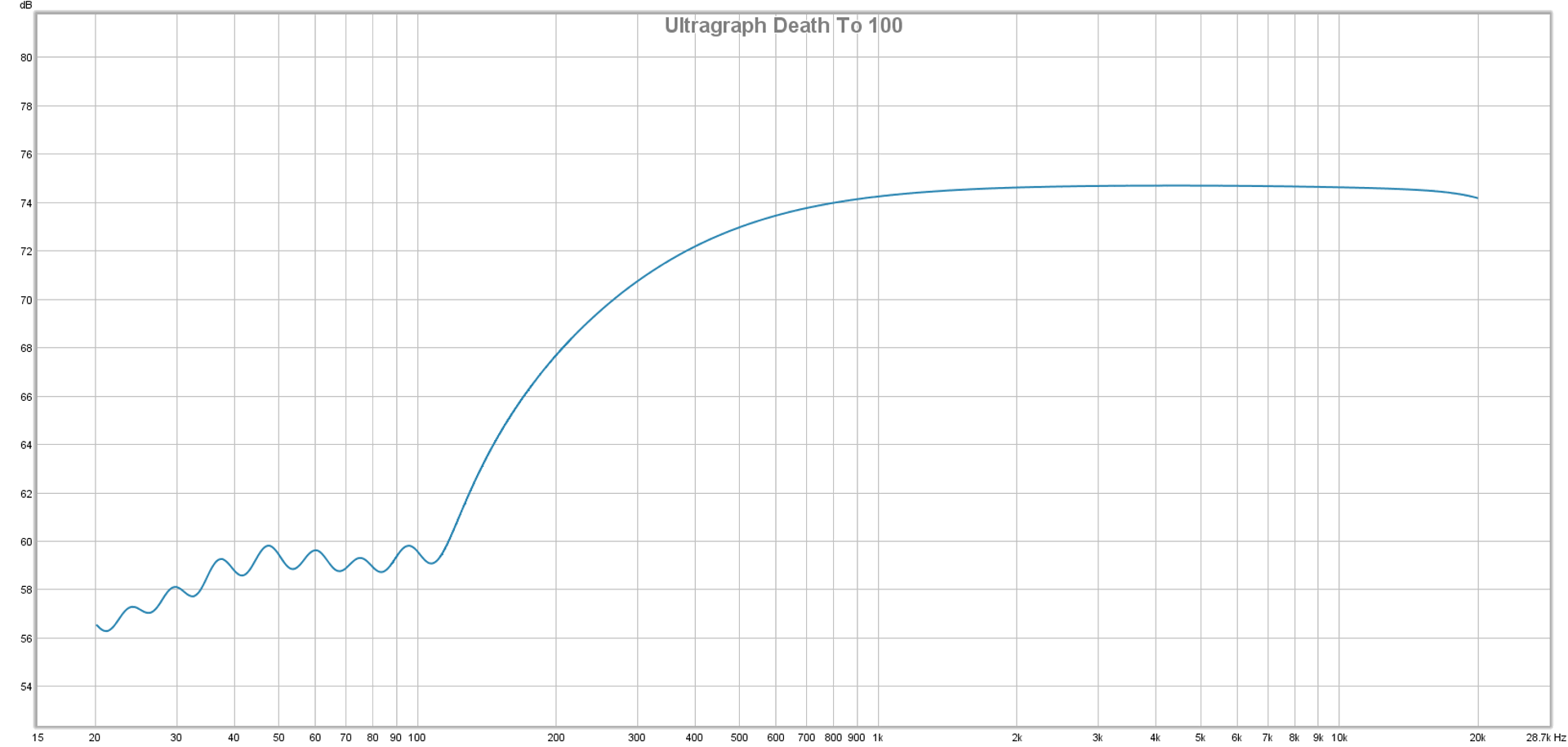

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

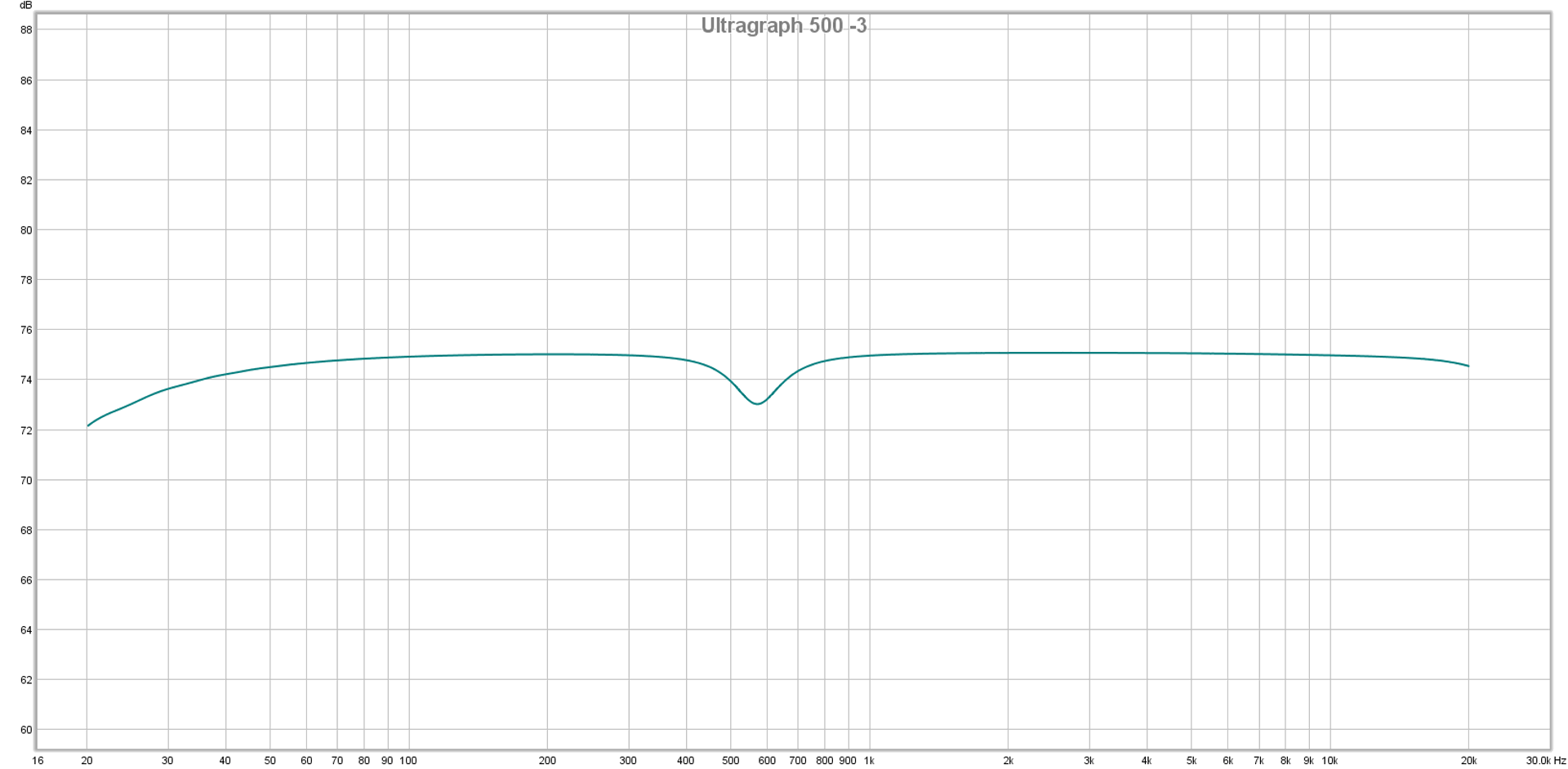

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.Dear Event Planners,

My name is Danny Maland, and I’m what would commonly be called “a sound guy.” A/V. An audio human. Show crew. That kind of thing. I’d like to take a moment to address an issue that has caused me some problems over the years. I don’t know if it’s trending towards worse or better, but as a person with an engineering mindset, I usually pick “assume the worst” and go with it.

Now, before you mentally check out, please be assured that I’m going to stay away from snarky finger-pointing here. We’re all on the same team, and actually, I think that production has not always been good at being on the same team with you. My feeling is that we spend lots of time failing to explain our needs to you, and so assumptions get built that lead to poor outcomes. With that on the table, let me lay out the crux or nexus of this whole thing:

When it comes to the spacetime continuum, production needs a lot of it. A lot of all of it – both space and time.

There’s a significant amount of pressure out there to compress both schedules and square footage. Time is money, space is money, and both together are a lot more money. Clients like to save money, and so do I, but value-engineering live music is not something I can recommend. Any show, even one that is a repeat performance, is itself a singular event that can never be repeated. All of us have exactly one chance to get it right, and squeezing anything that supplies the endeavor (space, time, electrical power, etc.) increases the chance of a trainwreck.

You don’t want that, and neither do we.

As an event planner, I’m going to guess that you like specifics. So here are some for you to consider about space and time.

1) If you’re going to have a full band with pro-production at an event, please consider a 20 foot wide by 20 foot deep area (or about 37 square meters total) to be the bare minimum space for it all to happen inside. I know that some people will say, “That’s overkill!” but I really do mean this. Bands that are forced to be right on top of each other don’t perform to their full potential, and close quarters makes for mic-to-mic bleed that hampers a good mix. Feedback also becomes a real pain when the performers are in very close proximity to the PA system. Yes, some permanent venues have a smaller area to work with, but remember that we may be bringing everything with us. We don’t have the ability to do a fully maximized and tweaked install at the drop of a hat. We need cushion, especially when we’ve just loaded in and everything is spread out.

2) For scheduling, please have any production that’s self-contained with the music set to arrive a minimum of four hours prior to soundcheck. If you’re in a situation with no real loading dock, add another hour or two. We need lots of time to set and tune, especially when the space is one we’ve never been in before. You might think you want us to “throw and go,” but that’s not going to get you great results. I’ve gotten lucky on plenty of throw and goes, but not so lucky on others. I don’t think you want your event to be a luck-based mission. That’s too much uncertainty with too much money and reputation on the line.

The client may push on these things. The event space may try to get you to cut down. Please stand firm! We need your help to get this right.

So, that’s it. Let’s be sure to uncompress everything and work towards better results. Like I said, we’re all in this together. Our success is your success, so let’s work as a team to produce amazing things.

Best regards,

Danny