Take things personally, but not too much.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

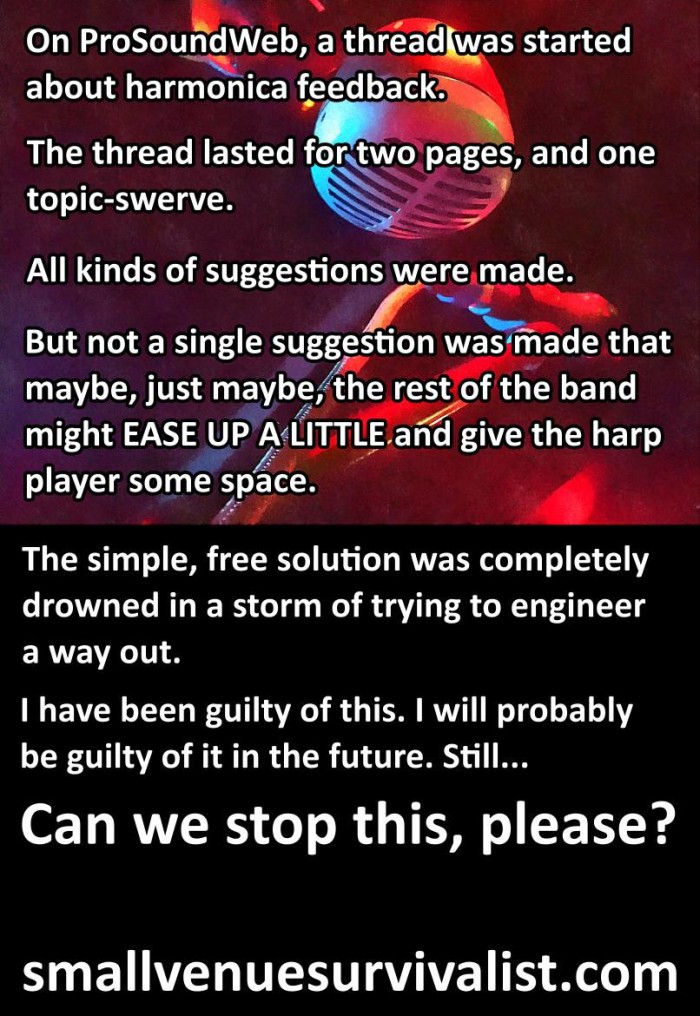

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.You don’t know me, and I don’t know you. This is mostly because you’re not any particular person. You’re an aggregate character, an archetype that makes a regular appearance in one form or another. You have many avatars. These avatars ask questions, sometimes in person, sometimes on the Internet.

You’re worried.

You’ve been trying to do good work. You’re conscientious, always trying to get a better handle on your craft. You’ve had a string of shows that you felt good about, and then “it” happened. A band was booked at your place of work, and the results were nightmarish. The whole night felt like moving a rope by pushing it. You couldn’t get your mix to behave. The different parts wouldn’t blend together into a satisfying, holistic sound. Instead, you sat through several hours of sonic “Whack A Mole,” where one thing would be too loud, and then the next thing would be too loud, and then a whole other thing would be too loud.

In short, the show “fought” the whole way.

It was a roaring storm that improbably managed to combine shuddering murk with piercing shriek, and it made your ears hurt. It made other folks’ ears hurt. If you could have visualized the sonic splatter, it would have made a hyperactive toddler armed with pureed carrots and applesauce seem quite manageable.

You’re wondering if you’re any good at this audio stuff. You’re wondering if your reputation, and the reputation of the room you work for, have now been irreparably damaged. You may be storming around, barking exasperated questions like, “Why won’t musicians help me out? Why won’t they listen to me? What am I doing wrong?”

It’s good that you’re taking things personally. The truly awful people in the noise-louderization business don’t take any responsibility at all. They don’t bother to even consider if they should worry. They’re always right in their own mind, and you have managed to dodge that bullet. You want quality, and you’re willing to try for it. It bugs you when other folks aren’t on board. It worries you that maybe you don’t have a magic touch with audio; If you did, wouldn’t you be assured of perfectly consistent results?

I’ve been down this road. I still travel across it from time to time. I want to tell you to keep worrying, but not so much that you can’t put the worry aside and enjoy things.

Because, especially in live sound, you can’t fix stupid.

I realize that sounds very harsh. We’re supposed to be friends with, and respect musicians, and to say such a thing might bear the appearance of contempt. But it’s not contempt. It’s simply recognizing that the life of an audio human is to translate to the audience what’s already there (especially if you’re in a smallish room, where the band’s acoustical contribution is overwhelmingly high). If what’s already there isn’t much good, then everybody’s out of luck.

Our profession has a tendency to be compared to studio engineering. We use very similar tools. The basic vocabulary is the same. Shouldn’t we be able to overcome any difficulty? Get any drum or guitar sound we like? Tame any runaway sonic event? Massage any fractured ensemble into a respectable, even enjoyable gestalt?

Well, no, actually, because different disciplines can share both tools and vocabulary.

I have said this many times, but I will say it again. We are at the mercy of limited power, limited volume tolerance, and limited gain-before-feedback. The studio guys get to live in a world where all the audience hears is what comes through open-loop, after-the-fact playback. We, on the other hand, occupy that portion of the universe where life is realtime, where every part of the system interacts with and potentially destabilizes some other part of the system, and where completely reinventing the band would require us to be so loud as to require everyone to wear both earplugs and gun muffs.

The way the band sounds naturally is pretty much how they’re going to sound with a PA. A great PA, with truly top-shelf FOH control, in a very big room (or outside) will give you more options, but not infinite possibilities. Physics is a harsh mistress, because she makes no exceptions, but she is also a fair and ultimately predictable creature – also due to her not making any exceptions. As you get better and better at your craft, you will more readily identify just how much you can help a band along with what you have. You should use this power tastefully and wisely. You should ask yourself if you’ve done everything you know how to do, because that’s part of being a pro.

But you shouldn’t agonize, because you can’t fix stupid. None of us can. I have never, and you will never make a bad band sound good. It’s physically impossible. If you “make” a band sound good, the band probably wasn’t actually bad. (Remember that last bit. It’s very important.)

So, keep being conscientious. Keep asking yourself how you can get better. Keep showing up on time and doing your homework. Keep taking a personal interest in a show having a great outcome.

And realize that there will be things you can’t fix. As long as you did everything that was prudent to do, you can’t blame yourself. There are people who won’t get that, but most of them probably won’t be signing your paycheck. Let the rough experiences sweeten those times when the band is so good that you can’t possibly screw it up.

Keep on mixing.