Often, the answer is “nope.”

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

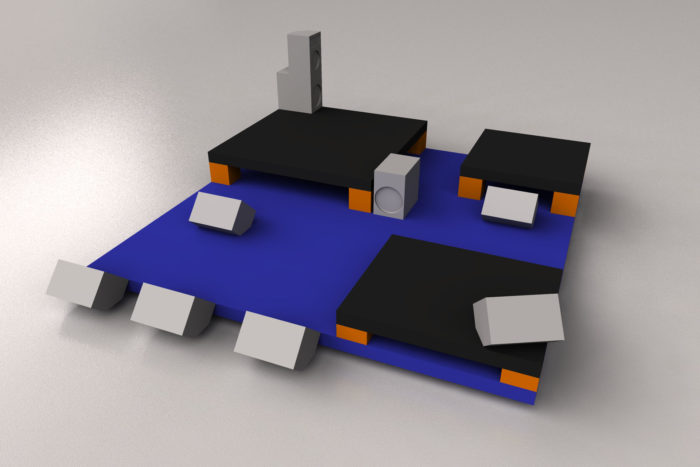

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.Monitor world is a PA system, just like FOH is a PA system. The only difference is that monitor world handles a few very small audiences, and FOH usually deals with one comparatively large audience. All the helpful AND problematic physics considerations are the same.

This being the case, the stage is yet another place where simply piling up more and more boxes (all doing the same thing) to get “more” can be counterproductive. A vocalist wants more vocal, but their monitor is already doing everything it can, so you add another box. Does it look impressive? Yes! Is it louder? Yes! Is it better?

Yea- er…well…wait a second…

What you very well might end up with is a different set of issues. If the singer isn’t precisely situated between the wedges, the wedge outputs arrive at different times. This means that all kinds of destructive phase weirdness might be happening, and that can lead to intelligibility issues. The vocal range is very easy to louse up with time-arrival differences, and a sensation of “garble” can lead to a player wanting even MORE monitor level in compensation. In that instance, you haven’t actually gotten anywhere; Monitor world is louder, but it’s not any easier to hear in the information-processing sense. You also have greater effective loop-gain with that extra volume rocketing around, which destabilizes your system.

Plus, the low-frequency information still does combine well, which can lead to a troublesome buildup of mud. This goes double for everybody who’s off-axis (and that’s probably just about everybody who isn’t the intended audience of those wedges). That makes them want their own mixes to be hotter, which compounds all your problems even more.

And, of course, there’s even more bleed into FOH.

The brutal reality is that, for any single sound that a given player needs to hear, that signal will always sound better coming from a single box that “can get loud enough.” More wedges (all producing the same output) can only combine less and less coherently as you add more of them.

“But, Danny,” you protest, “you’ve done dual wedges for people. You’ve even rolled out some really excessive deployments, like the one in the article picture. Who are you to tell folks not to do that kind of thing?”

Fair point! In response:

1) It’s because I’ve tried some strange monitor solutions that I can say they weren’t necessarily improvements over simpler approaches.

2) Sometimes you do things that look cool, accepting that you’ll have to deal with some sonic downsides as a result.

3) Just because you’ve piled up a bunch of wedges, it doesn’t require you to put the exact same thing through each enclosure. Somebody might have two boxes in front of them, but one might be for vocals only and the other for instruments only.

With some bands, especially those who are naturally well balanced and don’t need a ton of monitor gain, the extra fun-factor and volume bump can trade off favorably with the coherence foibles. As the rest of this article indicates, yes, I am in the camp that says that a single box will always “measure better.” However, there’s more to life than just “measuring better.” If you have some room to compromise, you can be a little weird without hurting anything too badly.

Audio is an exercise in compromise. If you know what the compromise factors are, you can make an informed judgement. If you know that throwing a bunch of boxes at a problem might cause you other problems, then you’ve got more knowledge available to help you make the right decision for a fix.