The funny thing about this article is that I was going to write it as the lead-off piece for this site – and then I got sidetracked.

Anyway.

I think small venues are killer. Killer places to work, killer places to play, and killer places to check out music. Of course, that just my opinion.

I think I can justify that opinion, though. As I see it, small venues have innate strengths to be found in their smallness. Sure, large halls, “shed” gigs, sizable festivals, arenas, and stadium shows have strengths. Lots of strengths.

And strength.

As in, “brute force.”

In the end, though, your local bar, all-ages room, or mini-theater can do things in a way that only they can really do…because they’re small. Also, my suspicion is that most of us are going to spend a lot of time working in small venues. There are only a few Dave Rats and Evan Kirkendalls in the world, who work on big rigs almost all the time.

Please don’t get me wrong! The guys and gals running the big shows have a lot of wisdom for us, but at the same time, I think we should try to identify and appreciate the advantages that we “little giggers” enjoy on a daily basis. This isn’t sour grapes! I think big shows are amazing creations, and that they would be very rewarding to work on.

The point is to appreciate the great things about the context that you’re currently in. Like…

Intimacy

Intimacy has become an overused word in the music business. However, it has become a cliched buzzword precisely because it’s actually important. Intimacy is probably THE main trait of the small venue, and it works for pretty much everybody involved – musicians, techs, and concert-goers alike.

For the musician:

Intimacy means that your audience is just a few feet away. Audience members can actually be interacted with as individuals, instead of as a giant mass. You can take a break, step off stage, and make friends with people in the crowd, all with ease. (That’s how you build an audience, by the way: You make personal connections with people.)

An intimate show seems more personal, because it is – every word and note becomes potent, because there’s so much less inertia. Huge crowds are certainly fun, but if a big chunk of them aren’t on your side, you will probably only notice the hostility – the few people who love every second are invisible, swallowed up in the monster. At a small venue, the people who like you are much easier to hear, see, and connect with. They don’t get lost in the crowd, and because the crowd is small, it’s easier to “turn” a visible portion of the audience towards your favor (assuming you have the skill to do so.)

For the tech:

Small shows are great because communication with the folks on stage is (usually) much easier. You don’t have to have runners and comms. All you need is a talkback, and sometimes you don’t even need that. If something needs fixing on stage, you don’t have to discuss what it is with monitor world, and then get someone to do what’s needed. You just walk up there and deal with it.

When you work in close proximity to the artist, it’s easier to figure out what they need. It’s also much easier to get to know the artists as people, and become friends with them. This also makes it much easier to work with the artists, because knowing people helps you understand their needs and how you can fulfill them properly. If the artist is your friend, or at least known to you as an actual person, it’s a much shorter path to being on the same team.

Successful shows are all about teamwork, by the way.

The other great thing about an intimate show is that you can actually get to know the audience – you know, the OTHER people you’re there to serve throughout the night. In the same way as the talent, you can get to know the audience as actual people. You can make eye contact, and even talk to them. You can even become friends with them!

It’s not impossible to connect with audience members at a big gig, but I don’t think it’s as easy.

For the concertgoer:

For the folks in the crowd, intimate shows are great because all the seats are “expensive,” without actually costing an arm and a leg. Think about it: People pay insanely large sums to sit in the first few rows at big gigs, because that’s where you can actually see what the artist is doing in a direct way. I’m not saying that huge video walls aren’t cool, but they just aren’t the same as being able to see what the band is doing with your own two eyes. (Again, if it was the same, then there wouldn’t be a market for the first few rows.)

Then, there’s the whole “meet and greet” thing. At small shows, the chances are much higher that you can actually say hello to the players and shake hands. The chances are astronomically higher that you might even be able to have a real conversation, because fewer people are competing for the artist’s attention. Often, you can just walk up to the musicians with ease, because there’s no need for a bunch of security humans (and a barrier) 20 feet away from the downstage edge.

This also works for the folks who want to see how the production is done. Especially at bar gigs, people curious about how the lighting is rigged, or the PA is stacked, or how the console is set up, can usually go right up to the appropriate person and ask. They can walk over to the rig and take a gander. Again, the bigger show, the harder it gets to find out how it all comes together. It’s not impossible, of course, just more challenging.

Flexibility

Another great thing about small venues is that changes and problems don’t necessarily wreck a show, because there’s a greater ability to “flow” around the issues. If something needs to change in a hurry, it’s often easier for that to happen at a small show.

For the musician:

Flexibility means that if you want to change the order of a multi-act show, you can do it without a massive disruption. You can also change your set around, bring up guest musicians who will just take care of themselves (because they don’t necessarily have to get put into the PA), and generally make changes on the fly. The reason is because there’s so much less in the way of logistical choreography that has to happen. Sure, every change has an effect, but the number of people who have to coordinate for the change to happen is small.

For the tech:

Small-venue flexibility is great if you have limited resources. Not enough mic-lines? Chances are that extra amp on stage can carry things without your help (if the musicians are good). Need to change the lighting a bit? Well, since there are only a few instruments, you can just “grab and go.” Heck, you might even be able to reprogram most of the show in a few minutes. Need to change something about the PA? A small sound system is easy to reconfigure, if you have the tools, because the number of pieces involved is quite manageable. Again – the choreography required to make a change is minimal.

For the concertgoer:

Flexibility is great for concertgoers, because the show can go on even when problems crop up. Lose the whole PA for some reason? You’re pretty much screwed in a giant space. In a small venue, the opportunity for an amazing, all-acoustic rescue is still there. Did an act drop out suddenly? Putting in a replacement band isn’t a huge process.

(Very cool, spontaneous things can happen at big shows, too. It’s just not usually as easy. There are a lot more people involved, a lot more gear involved, a lot more logistical issues to work out…you get the picture.)

Freedom

Another wonderful something about small-venue shows, where the logistics are far more contained and the stakes aren’t astronomically high?

There’s so much more freedom to experiment.

For the musician:

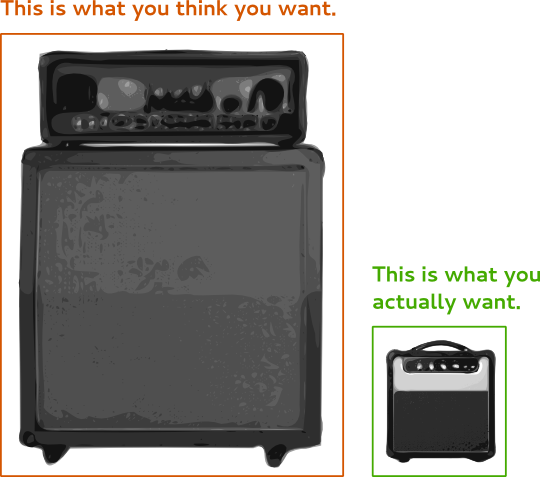

If you want to try out your new songs, the ones you’re unsure about, you can. There’s less at stake than at a huge gig. Also, if you want to try out some totally weird amp configuration or exotic instrument, you don’t have to do a bunch of tech rehearsals. You can just try it, and if it doesn’t work, so what? You only lost, what, ten minutes? (Of course, you have to know when to abandon an experiment for the time being. Not everybody does.)

For the tech:

Because a lot of small-venue shows tend to be free of highly-specific tech-riders, the house crews can often experiment as far as their budgets will allow. If you don’t have a lot of BEs (band engineers) asking for specific console and processing setups, you can try your favorite configurations – or even opt for a “homebrew” digital mixer that would never be accepted on a normal rider. Want to use your favorite mics, the ones that don’t normally get asked for? No problem – very few acts will be requiring a certain transducer for any particular instrument or vocal. (Just make sure your favorite mic is actually a good choice for that application.) Want to try a new lighting fixture or two, maybe do something unconventional? Give it a shot! It’s unlikely that the acts will be bringing in an LD (lighting designer) who’s absolutely got to have all industry standard gear of a certain “grade.”

I should definitely mention that I think there’s an “uncanny valley” for experimental freedom. In the small-venue world, you can experiment because there are fewer people to please, and they are usually easier to please. The limitation is resources.

Then, there’s a vast middle-ground where people aren’t interested in pushing the boundaries, and just want what’s worked for them for however long. In the middle ground, you’re subject to the whims of bands, management, and tour crews who aren’t interested in your crazy notions, and who tend to be notably risk-averse.

After that, though, there’s the point where you “leave the valley.” That’s where you have the stature, trustworthiness, and resources of, say, Dave Rat, and can freely try all kinds of neat things again.

New Music

I’ve been known to say that “every huge, international act is a local band somewhere.” I say that because there’s sometimes a stigma attached to the term “local band,” as though bands that are just starting out and have a limited fanbase are somehow inferior.

It’s just not true. There are tons of acts that could eat [insert huge artist’s name here] for breakfast, and who just aren’t widely known for whatever reason. Besides, every huge act (that isn’t a “manufactured” group) started out playing in the bars and clubs. They had to grow into their big shoes. They had to start somewhere.

To me, the implications are clear: If you want to create new music, have a chance at hearing new music, work with people making new music, and just generally “be present for the creation,” small venue shows are the ones to look for. The sound isn’t always great, the number of lasers in the light show is small or zero, and the roar of the crowd isn’t as loud.

But the small venue is where a ton of really worthwhile things get their start.

The big, red note is what musicians think they’re getting paid for. Actually, most musical acts are paid for their ability to bring out the people in the foreground.

The big, red note is what musicians think they’re getting paid for. Actually, most musical acts are paid for their ability to bring out the people in the foreground.