The material that’s critical for a mix is between about 200 Hz and 4000 Hz.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

We’ve all seen and heard it, in some way. You know what I mean. The “smiley face” EQ. “Scoop” switches. The midrange all the way down – and, optionally, the bass and treble CRANKED.

“Hi-fi.”

“Bedroom tone.”

Heck, most of us have been practitioners of this very thing. When trying to make something sound impressive, polished, and big, ruthlessly carving out the midrange is like the Dark Side of The Force: Quick, easy, and seductive.

Also, really bad for you in the end.

What a mix (live, studio, monitors, stage-volume, anything) actually stands or falls on is the midrange. Sure, you want the top and bottom octave to be in the right place, but they really aren’t as critical as you may have been led to believe.

So, why do people de-emphasize the midrange so much?

Tough, Lonely, Unexciting Rooms

There are all kinds of contexts that drive scooped, sizzle-thump tones. Getting into every detail could make for a very long, barely readable article. I think that you can get a decent picture by generalizing, though:

Midrange is common, unexciting, and – due to its criticality – annoying when it’s wrong.

See, humans hear midrange better than almost anything else. We’re great at detecting and analyzing human speech, because our lives basically depend on it. Human speech is all about midrange, and expressive, detailed vocalization is one of the things that makes humans actually…you know…human. We grow up hearing midrange. We communicate using midrange. We hear midrange all the time, in every possible place, in all kinds of contexts.

Midrange? More like, mundane-range.

When we come across a sound-generating item that can do the bits of the audible spectrum that are outside the boring and everyday, we fall in love pretty fast. “Bass” and “air” are like candy to our common meal of mid. They’re impressive. Fun. Exciting. Everything that those pokey, old-hat mids aren’t.

So, there’s a strong temptation to emphasize the fun bits at the expense of the boring parts.

At the same time, our particular human genius for detecting problems and unnatural weirdness in the mids makes us intolerant. Our brains are also VERY good at synthesizing missing information, especially when a lot of the basic cues are still intact. If your stereo or amplified instrument are in a not-so-acoustically-nice room, a quick fix is to yank out as much of the troublesome midrange as you can. The music still sounds fine, because the mids are still audible enough for you to imagine whatever you’re missing as you revel in the sounds that are emphasized.

The success of this is further enhanced by being alone, which is what leads to “bedroom sound.” With nothing else “in the mix,” you can hear your instrument just fine – and it sounds GREAT! All the midrange problems are sucked out, and the impressive “body” and “top” ends are dialed way up.

Awesome sauce.

Until real-life intervenes, of course.

Midrange Makes Mixes Musical

In the context of modern music, especially in small venues, what you have is an assemblage of amplified sounds that coexist with a lot of acoustical goings-on. For example, take a typical rock band’s rehearsal space. You’re probably going to run into an un-miced drumkit, one or two guitar amps, and a bass rig. The guitar and bass players, through electronics, have very immediate and dramatic control over the timbre of their instruments. Within the limits of their instruments and amplifiers, they can dial up some wild and weird tones.

On the other hand, the drummer can’t go quite as crazy. Sure, there’s a lot of variation to be had from shellpack to shellpack, especially with different heads, tunings, sticks, and everything else, but the reality is that most acoustic drumkits impart a tremendous amount of midrange into the room. If nobody else has much midrange left over, then the kit is going to obliterate the tonal parts of the song arrangements…unless, of course, the guitar and bass rigs are much louder than the drums.

So, here’s the major thing:

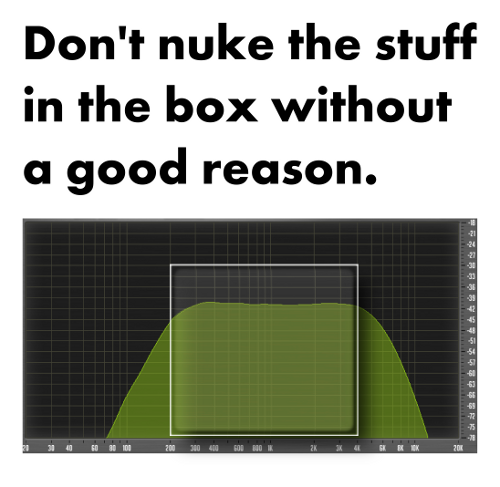

Sufficient midrange content is the primary and essential component of a tonal instrument’s place in a mix.

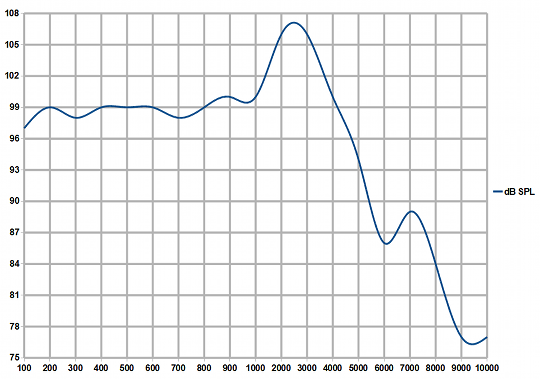

The reality is that, for all the excitement and fun that low and high-frequency information give us, there is very little actual music that occurs far below 200 Hz, or far above 4 kHz. It’s not that there isn’t ANY musical information beyond those areas – of course there is – it’s just that it usually isn’t critical to the actual song.

(Yes, bass guitars produce lots of fundamentals that are around or below 100 Hz, but the reality is that we mostly end up listening to the harmonic content of what the bassist is doing. Seriously – find yourself some songs with prominent, melodic basslines. Load the files into a DAW and filter everything below 200 Hz. I’ll bet that you can still hear the bass-human doing their thing.)

If the midrange content of a given part is de-emphasized in a big way, there is a very good chance that the part will disappear in an ensemble context. The flipside is that allowing everybody to have their own piece of the mids means that you’re much likely to get a better mix…especially when you’re playing live in a small room, where the interplay between purely acoustical sounds and amplified tones can be either beautiful or horrific.

Practical Considerations

The biggest take-away from this is that everybody – guitar players, bassists, vocalists, monitor guys, FOH (Front Of House) humans, and anybody else that I’ve missed – should resist the urge to “kill the mids.”

I should know, because I’ve had my own “scooping” bite me. Killed-mid vocals sound great in FOH and monitor world, right up until they have to be matched up with an actual band. At that point, you have to get the vocals VERY loud to get audible lyrics, and that can lead harshness, feedback, and an audience that wants to not be in the seats anymore.

I once had vocals dialed up in the monitors that sounded “super-studio.” Very hi-fi. It would have been great, except that when the band actually started playing you could barely hear the vocals in the wedges. You’ve gotta let those boxes “bark” a little if people are going to hear themselves sing.

On the flipside, I once worked with a band where one of the guitar players had a serious fascination with HF content. Once the drummer was playing, all you could hear out of that guitar was basically “eeeeeeessshhhh.” He would play these super-fast solos, but you couldn’t hear what he was doing. His actual notes were dialed out so far that, even when he was painfully loud and clearly in front of everybody else’s volume, you still only had a sort of screechy, clicky hiss to listen to.

There’s even a “technologic-economic” side to the whole thing. Making lots of low end and high end are tough things to do with an amplifier or a PA system. Killing the midrange and cranking the ends means that you’re probably wasting a ton of internal headroom and power-stage output on material that might not even be audible. If you want that material to be audible, you need lots of power and lots of speakers – and that’s spendy. Want to get the most out of more affordable gear? Get the midrange in the right place as the first step, and then use what you’ve got left over for the top and bottom.

The mids can be tough to love at first, but it’s a worthwhile relationship.

Very reliable, but not the only valid technique.

Very reliable, but not the only valid technique.